Sara Fanny Hockey: Benjamin Britten (ca. 1920)

(National Portrait Gallery)

As a composer, Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) showed his skills early, composing his first works at age 5. He started piano lessons 2 years later and the viola when he was 10. In his prep school, South Lodge, Lowestoft, he wrote music… in his words, he “wrote lots of it, reams and reams of it.”

He kept these youthful efforts and periodically revisited the works, seeking inspiration for his current projects. One of these works was his Simple Symphony. In 1933-34, Britten was seeking ways to make a living as a composer. He looked at the schools market, with all of the school ensembles, and wrote his work to be played either by string orchestra (for the bigger schools) or string quartet (for the smaller schools).

He mined his juvenilia for material, and everything from songs to parts of a piano concerto he wrote at age 13 appear in his later works, particularly the Simple Symphony. Each movement uses two of his childhood works as its inspiration, and yet, although we have a simple work that well within the technical accomplishments of amateur school orchestras, at the same time he created a work that is played with equal fascination by professional adult orchestras.

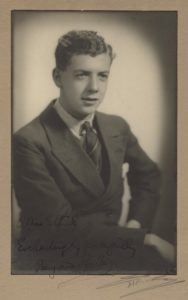

Frank Arthur Swaine: Benjamin Britten

(ca. 1930)

The first movement, Boisterous Bourrée, took its inspiration from a 1925 piano suite and a song (‘Now the King is Home Again’) that used a lyric by Alfred Tennyson that he’d written in 1923. The ‘bourrée’ is a French dance, widely used at the French court in the 17th century, with a distinctive 4-bar rhythm, one feature of which is a short pickup, heard at the very beginning of the work.

Britten: Simple Symphony, Op. 4: I. Boisterous Bourrée (Northern Sinfonia; Steuart Bedford, cond.)

The second movement, beloved of young orchestras because of its extensive pizzicato technique, comes from his 1924 Piano Sonata, and song, based on a text by Rudyard Kipling, also from 1924. Plucking the strings gives this a very percussive flavor, with a bit of strumming occasionally.

The slow movement, Sentimental Sarabande, uses a theme from another piano suite from 1925, and a 1923 Piano waltz. The music sounds like the mature Britten in a way that the earlier movements do not – a lyricism bespeaking a great sentiment that’s being held back.

The final movement comes from his ninth piano sonata of 1925, and yet another song from 1925. After the seriousness of the third movement, the Frolicsome Finale, carries us away – it’s almost like Elgar in some of its flights of musical fancy.

What’s impressive about this work is not only the work itself but also that it uses themes from music written he was only 9 years old. Few children are composers (far more are math prodigies) and even fewer are writing material that their 20-year-old self could reuse to create a work that, as one writer said, was “memorably tuneful, technically polished and superbly conceived for the medium.” It also speaks to the talented composer that Britten was, even as a 20-year-old.