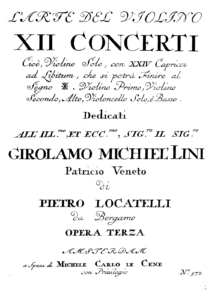

L’arte del violin first edition

What is a capriccio? It has its roots in late 16th-century Italy, where it was used to describe a set of madrigals by Jacquet de Berchem in 1561. According to Furetière in his Dictionnaire universel (1690), ‘Capriccios are pieces of music, poetry or painting wherein the force of imagination has better success than observation of the rules of art’. That seems to leave the field open to the imaginative composer and so, over time, the capriccio became a musical place for ‘the exceptional, the whimsical, the fantastic and the apparently arbitrary.’

Music with sudden changes of idea, sudden changes of mood, violent changes of style became the norm. The rules of counterpoint could be broken at a whim, all in the interest of affect. Through the 17th century, the capriccio became the place for wild experimentation and fantasies of composition.

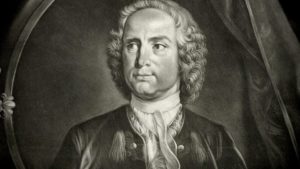

Pietro Antonio Locatelli

In the 18th century, with the rise of the international virtuoso, the cadenza, the place in a composition such as a concerto where the soloist could make his own wild experiments on the material presented by the composer, took on the name of capriccio. Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764) used the name ‘Capriccio’ in his set of 12 L’arte del violin, Op. 3, violin concertos. Each concerto’s outer movements (movements I and III) became a place for the technical and virtuosic skills of the performer to be exhibited.

Locatelli was born in Bergamo, Italy, and by age 14, was studying in Rome, if not with Corelli, then with the school of Corelli. He came to the attention of the major-domo of Pope Innocent XIII and came under papal protection. After Rome, we next find Locatelli in Mantua, where the governor of the city gave him the title of virtuoso da camera in 1725. He was next in Venice and in 1727, he was at the court in Munich and then in Berlin, Frankfurt, and Dresden. We don’t know a great deal about what he was doing, but he shows up in various court documents, so we are able to trace his path around Europe. By 1729 Locatelli was in Amsterdam, which in the early 18th century, was the heart of the music publishing industry, that paired advanced printing techniques with an efficient commercial network. In 1731, he received permission for a 15-year license to publish his own works, with the licence being renewed in 1746.

Henryk Szeryng

The importance of Locatelli’s L’arte del violin in 1733 cannot be understated. His sheer demands of virtuosity on the performer was game-changing for the next century. He was writing in the most advanced style of his day and this continued to be influential, particularly in France, through the beginning of the 19th century. The range of notes demanded of the player remains a challenge even today.

The last concerto in L’arte del violin being the Capriccio No. 23, marked not only “Allegro” but also ‘Il Laborinto Armonico (The Harmonic Labyrinth).” The title seems to be purely about technique, not about a harmonic puzzle. The range of notes seems to go up into the ultrasonic. Performers consider this capriccio to be one of the most difficult, even today, in the whole violin repertoire.

Locatelli: Capriccio in D major, Op. 3, No. 23 “Le Labyrinthe Harmonique” (Arr. Ferdinand David)

Locatelli’s capriccios were highly influential, inspiring the demon virtuoso who followed him, Niccolò Paganini to write his own set of 24.

The performer here, Henryk Szeryng (1918-1988), was a Polish violinist who later took Mexican citizenship when he became the head of the string department of the National University of Mexico in 1945. He had essentially retired from the concert stage when he was heard by the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, after a Rubinstein concert in Mexico City in 1954, and he persuaded him to go back on the concert stage. Szeryng and Rubinstein toured and recorded together, sometimes joined by the cellist Pierre Fournier, for the rest of their careers.

Performed by

Henryk Szeryng

Gabriel Bouillon

Orchestre de l’Association des Concerts Pasdeloup

Madeleine Berthelier

Recorded in 1950 – 1952

Official Website