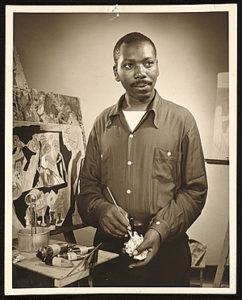

Jacob Lawrence

In recent years, migration has meant the vast movement of peoples across West Asia and Europe and the Americas, seeking shelter from military action or economic inaction. At the turn of the 20th century, in America there was also a great migration, but this was movement by an internal group, heading from the south to the north.

American painter Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) created his 60-part Migration Series and it brought him fame at age 25. He was showing the great migration of America’s black population in the early 20th century from the farming, rural south, to the north’s urban centers. The migration happened by train and brought jazz to Chicago and the Harlem Renaissance to New York.

Derek Bermel

This two-year project, done between 1940 and 1941, involved the creation of the captions and preliminary drawings and then preparing 60 boards, with the aid of his wife, artist Gwendolyn Knight. Because he was working in water-based tempera, and not in oil, and to keep the colours consistent across the paintings, each color was applied to each of the 60 canvases at one time, requiring him to keep all 60 paintings active.

The style is simple but with a crisp line, the images are stylized and not intimate. You’re always observing from a distance, which enables the viewer to take a larger view of a very complex situation.

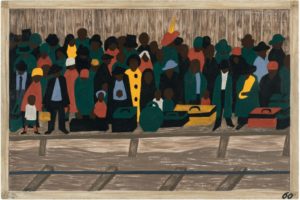

Lawrence: Panel 3: In every town Negroes were leaving by the hundreds to go North and enter into Northern industry. (1940–41). From every southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north (1993 caption).

The series was shown in New York in 1941 and, after much competition, the entire series was purchased by The Phillips Collection in Washington and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, with the even numbers going to New York and the odd numbers to Washington. In the images below, both the original captions and the revised captions Lawrence made for a 1993 tour of the series are included.

Through his images and captions, Lawrence details the reasons for the migration (child labour, crop failures, floods, discrimination) and what the reception the migrants had in the north, both positive (better educational facilities and the chance to vote) and negative (poor housing, harsh working conditions, and more discrimination).

Lawrence, Panel 15: Another cause was lynching. It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this (1941 caption). There were lynchings

(1993 caption).

The American composer Derek Bermel (b. 1967) was commissioned by Wynton Marsalis, as head of Jazz at Lincoln Center, for a piece that combined the ensembles of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and the American Composers Orchestra. His Migration Series for Jazz Ensemble and Orchestra (2006).

As befits a work such as this, written for such a varied ensemble, Dermel puts everything into the mix: classical forms and structures, jazz, blues, American folk music, just for a start. Just as in Lawrence’s panels, people are on the move.

Lawrence, Panel 26: And people all over the South began to discuss this great movement (1941 caption). And people all over the South continued to discuss this great movement (1993 caption)

The repression of the black southerners was not only economic but also murderous.

Bermel: Migration Series: II. After a Lynching

Lawrence, Panel 52: One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis. (1941 caption). One of the most violent race riots occurred in East St. Louis (1993 caption).

As people went north, they wrote letters back home, news and rumours spread through the communities as they considered what could be ahead of them.

Bermel: Migration Series: Interlude 2 – III. A Rumor

Life in the north meant hard work, poor housing, and race riots. In East St. Louis, the population shot up by 10,000 between 1916 and 1917. When blacks were taken on to help the Aluminum Ore Company break a strike in 1917, the city went up in flames. More than 6,000 black residents fled the city. The violence was protested all over the US, with 10,000 people joining in a silent march down Fifth Avenue in New York demanding equal rights for blacks all across the country.

Lawrence, Panel 60: And the migrants kept coming

(1941 and 1993 caption).

Life in the north also meant access to education, the freedom to vote, and the opportunity to succeed. Even after Lawrence finished his series in 1941, the onset of WWII brought more people out of the south. In his final panel, Lawrence shows us the migration never really ceased. In 1900, 92% of blacks lived in the south; by 1970, only 53% remained.

Bermel: Migration Series: V. Still Arriving

Lawrence captured an extraordinary time in America – where black southerners collectively took a stand against the life they had and migrated to a place where they could start again. In his music, Bermel joins a jazz orchestra and a classical orchestra to show how, even in music, our lines should be much more fluid and accepting of other styles and ideas.