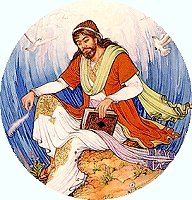

Hafez

It has been said that every Iranian household contains two books, the Koran and Hafez. And a little saying suggests, “While one is read, the other is not.” More than 600 years after his death, the 14th-century poet Hafez of Shiraz is still Iran’s national hero and just as popular as he was during his time. His brilliant use of metaphors in the native Farsi language has united people over centuries.

Don’t make me fall in love with that face.

Don’t let the drunk the wine seller embrace.

Sufi, you know the pace of this path.

The lovers and drunks don’t disgrace.

The mystic poetry of Hafez regales in the joys of love and wine, but it also targeted religious hypocrisy. Its ironic tone is widely believed to be a critique of the religious and ruling establishments of the time. With his imaginative references to monasteries and convents, he ignored the religious taboos of his period, “and he found humor in some of his society’s religious doctrines.” Many of his poems are still used as proverbs and sayings today, and his mischievous sense of irony greatly appealed to European poets and composers.

Tomb of Hafez

Hafez (1315-1390), born Khwāja Šamsu d-Dīn Muḥammad Hāfez-e Šīrāzī, wrote in the literary genre of lyric poetry, known as ghazals. He deals with love, wine and taverns, presenting the ecstasy of diving inspiration and freedom from restraint. One of the most celebrated Persian poets, his work made a huge impression in Europe around the turn of the 19th century. Goethe wrote several Hafiz-inspired lyric poems in his West-östlicher Divan collection, and he remarked, “Hafez has no peer.”

His poetry has been referred to as one of the seven great literary wonders of the world, and he was venerated by such figures as Nietzsche, Garcia Lorca, and Brahms! Brahms found Hafez via Georg Friedrich Daumer, a poet and philosopher who wrote graceful but very free imitation of Hafez poems. Daumer produced two collections of poetry entitled “Hafis,” and Brahms was greatly taken by the sometimes mournful and sometimes celebratory moods of the poetry.

Georg Friedrich Daumer

You are thinking of something bitter to say

But now nor ever might you cause offense

Although you are so angry.

Your harsh words

Founder on coral cliffs

But become pure grace.

For they must, in order to cause shame,

Sail over a pair of lips

Which is Sweetness itself.

Erich J. Wolff

Richard Wagner was full of praise for Hafez, which he read in the free translation by Georg Friedrich Daumer. Wagner writes to a friend, “The acquaintance with Hafez has truly filled me with awe; we should remain greatly ashamed of all our pompous European intellectual culture before that which was already brought forward long ago in the Orient with such certain, sanguinely sublime spiritual calm.” Wagner was getting rather excited and he wrote to a fellow poet, “This Persian Hafez is the greatest poet that ever lived and wrote poem. If you don’t get yourself the poems immediately I will thoroughly despise you.” Although Cosima Wagner wrote in her diary “Richard often quoted Hafez,” the composer did not set any of his poems to music. However, Erich J. Wolff (1874-1913), a close friend of Zemlinsky and Schönberg, did. During his short life, Wolff wrote more than 180 songs, three melodramas, various piano pieces and a violin concerto. His Hafez settings date from the last two years of his life and exude simplicity and sophistication.

Viktor Ullmann

On 8 September 1942, Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944) was arrested and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. He had studied law at Vienna University and took lessons in counterpoint and orchestration from Arnold Schönberg. Ullmann abruptly broke off his studies in Vienna and moved to Prague to take up a career as a composer and writer actively involved in music education. By the time of his arrest he had published 41 opus numbers, and his portfolio contained numerous other finished works. Only thirteen printed works, which Ullmann had entrusted to a friend for safekeeping, survived the German occupation. Ullman remained musically active in the concentration camp, as he wrote to a friend, “By no means did we sit weeping on the banks of the waters of Babylon. Our endeavor with respect to arts was commensurate with our will to live.” Ullmann was deported to the camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 16 October 1944 and killed in the gas chambers two days later.

Hafez is simply superior to any poets ever lived. It does not require the snobbish literary gods

to acknowledge him. It only require you who love poetry to read his poems to come to that inevitable conclusion.