What’s the Difference? Here’s My Approach

Last month I gave a masterclass at George Mason University School of Music in Fairfax, Virginia, the largest 4-year public university in Virginia. I heard four young cellists, and later addressed the full University Symphony Orchestra.

Often the greatest artists travel too much to have their own class of students, but they are engaged to present masterclasses. What’s the difference you might wonder?

Music building at

George Mason University School of Music

A lesson is most often one-on-one with the teacher. The student is usually not nervous, (unless their teacher is Janos Starker or Heifetz, or someone equally demanding), and a close and nurturing relationship is fostered. The teacher helps the student develop the technical equipment to play every style of music with ease, and to express the emotions of the music. He or she will start and stop frequently in the lesson to comment. The teacher advises on musical styles, performance practices, and interpretation.

Sometimes personal issues come up. It’s important the student feels comfortable to share whatever is troubling him or her. A private teacher is able to guide and mentor the student, and help him or her mature.

A masterclass is entirely different. The artist will hear several musicians who are strangers. There is an audience present, which usually includes other students, other instrumentalists and teachers, and sometimes the public.

The student may be nervous, especially if the artist giving the masterclass is a well-known figure in the music world. Similar to a performance, the student will play a large chunk if not an entire movement of a work, uninterrupted, followed by applause. In a masterclass situation, the artist will address the student as well as the attendees, with comments that involve and inform everyone present, engaging the audience as well as the individual playing. Discussion might feature interpretation, technical issues, which affect every player of that instrument, and it presents a rare chance to “try out” body language, and stage presence. I often learned more in a masterclass because I wasn’t physically engaged trying to play my best, while battling performance anxiety. I could pay more attention to the wisdoms unfolding.

The music building at Mason is gorgeous, and boasts beautiful facilities for music, dance, visual arts, arts management, theater, and film and video studies. We ascended to a spacious lobby with a view of the lush grounds set up with several rows of chairs, a makeshift stage, and the piano. The four cellists I heard were from different backgrounds, at different levels, and pursuing different degrees.

Saint-Saëns: Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 33 – I. Allegro non troppo

The first student played Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto. The orchestral accompaniment plays a huge chord on the first beat of the piece and the cello entry is an accented E on the second beat of the bar. I worked with the cellist to feel the downbeat throughout his body, even to the point of asking him to grunt, and stamp his feet on the downbeat, so the cello entrance, a reaction, or “bouncing off” of the downbeat, would be intense, even furious.

Dynamics in a larger setting have to be exaggerated, with greater contrasts—louds louder and soft sounds with presence. The second theme is more singing, more sostenuto, and requires full bows, a continuous warm vibrato, and a totally different sound quality.

The next student had difficulty with his bow hold, as so many do. I described the pull and push of the downbow and upbow, firmly holding the tip of his bow so the student would have to work against me. The bow stroke is a reaction to what the arm does. “Which fingers do the work in your hand?” I asked. The student wasn’t sure, but the audience could see the difference. When I said the bow stroke should be like spreading peanut butter everyone laughed.

Popper: Etude No. 29 in F-Sharp Minor

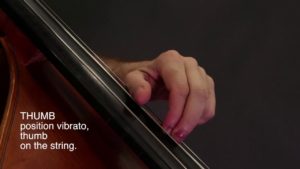

Another cellist tackled one of the thorny Popper studies—all in thumb position. Again, I addressed a technical issue, which plagues us all. Arm weight should push the strings down. The wrist must be level, not raised or dropped. The strongest position is when one can imagine a golf ball within the palm of our hand, fingers rounded, and the thumb knuckle at the base of the hand protruding not collapsing. The etude is still terribly difficult to play but I think everyone present had a better sense of how to feel comfortable in thumb position.

The final work Max Bruch’s Kol Nidrei is a piece very close to my heart. (Below is a link to a recent performance with a student orchestra.) “What emotions are you trying to convey?” I probed. Verbalizing evocative adjectives can sometimes be very helpful to inspire interpretation. I played the opening phrases and the audience responded, “Melancholy, heartbreak, despair.” “Yes,” I said. Our goal is to tell a story with our music-making.” This piece and many others have a purpose and deep meaning. It’s essential to research the pieces we perform to understand the composers’ intentions, which the musician should communicate, and important for us to ruminate about how to transport the audience with our tone, mood, and emotions.

Hopefully my suggestions will be incorporated in the next days and weeks, and some of the insights will be considered as the students develop in the future.

Hopefully my suggestions will be incorporated in the next days and weeks, and some of the insights will be considered as the students develop in the future.

It’s vital to participate in both lessons and masterclasses, and to perform as often as possible with amateur, student, and professional groups. Each experience offers valuable insights and different perceptions. How fortunate masterclasses from the greatest performers and teachers are available online to guide us on our musical journeys. As Starker used to say to me, the best musicians continually strive to grow and blossom as artists, for the sake of music.