Jüri Reinvere © Harri Rospu

In 2020, the world will celebrate Beethoven‘s 250th anniversary. Official events start on December 16, 2019, and run until December 17, 2020. The main events are concentrated around Beethoven’s birthplace in Bonn, Germany. In Bonn, Beethoven’s home has been reopened to the public as a museum after renovation, and there you can see Beethoven’s scores and instruments, as well as the notebooks he used to communicate after going deaf in 1801. Meanwhile, in Vienna, Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, will be staged by the actor Christopher Waltz at the Theater an der Wien, where the opera was first performed in 1805. In April, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra hosts a 24-hour Beethoven Marathon, whereas Bonn hosts a version of Beethoven’s unfinished 10th Symphony, completed by artificial intelligence. In May, the electronic music group Kraftwerk gives an open-air concert in Bonn in honor of Beethoven. The Beethoven year closes in December with a concert in the parliament building of Bonn, underlining the political significance of a composer whose “Ode to Joy” from his 9th Symphony became the EU anthem.

Miniature owned by Beethoven,

supposedly of Giulietta Guicciardi

As part of the Beethoven celebrations and contributions, the opera Minona by Estonian composer Jüri Reinvere will be given its premiere at the Regensburg Theatre on 25 January. Jüri Reinvere, who started his training at the Tallinn Music High School and attended the Fryderyk-Chopin-Music-Academy in Warsaw for two years before attending Sibelius Academy in Helsinki where he was awarded his master’s degree in composition, has been living in Germany since 2005. His list of works already contains several operas. In 2012, his Finnish-language opera Puhdistus (Purge) was given its premiere by the Finnish National Opera, based on a novel by Estonian-Finnish writer Sofi Oksanen. In 2014, his second opera, Peer Gynt, based on Ibsen’s famous play, commissioned by Norwegian National Opera, was staged in the same theatre. In recent years, he has written several large symphonic works and chamber music. In his newest opera, Minona, he deals with a mysterious story connected to Beethoven.

Beethoven’s rather stormy life consisted of many affections and stories with women. There were several muses in Beethoven’s life, among them singer Amalie Sebald, pianist Dorothea Ertmann, Hungarian countess Anna Maria von Erdődy, arts patron and philanthropist Antonie Brentano, and Therese Malfatti, cousin of one of Beethoven’s doctors. The best known of them is probably countess Giulietta Guicciardi, to whom Beethoven dedicated his famous Moonlight sonata.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2, “Moonlight” – I. Adagio sostenuto

Giulietta Guicciardi was the cousin of two other noblewomen, Thérèse and Josephine von Brunswick, daughters of the Count von Brunswick, from a Hungarian aristocratic family. One of the sisters, Thérèse von Brunswick (Teréz Brunszvik), was a pedagogue and a follower of the Swiss Pestalozzi system, also received a dedication from Beethoven for his Piano Sonata No. 24 in F-sharp major, op. 78, nicknamed “à Thérèse”. Her sister Josephine was probably the most important woman in the life of Beethoven.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 24 in F-Sharp Major, Op. 78

Teréz Brunszvik

There has been a long speculation since Beethoven’s death on who the “immortal beloved” in his life was. After Beethoven’s death in 1827, his assistant, Anton Schindler, found some letters in a hidden drawer. One of them was the famous Heiligenstadt Testament, the other a letter, written in pencil over 10 small pages. It reveals his feelings to an unnamed woman and ends with the lines: “Ever thine. Ever mine. Ever ours.”

The first assumptions about her identity were made by the same Schindler, the assistant (1840) who thought Giulietta Guicciardi was the “immortal beloved” of Beethoven. La Mara (1909) published Thérèse von Brunswick’s memoirs, which show her full of admiration of and adoration for Beethoven, and suggested that she could be the one. Wolfgang Thomas-San-Galli looked through the official listings of guests in Bohemia and at first (in 1910) concluded that Amalie Sebald was the “immortal beloved”. There have been many other hypotheses and studies.

A crucial moment came in 1957 when German musicologist Joseph Schmidt-Görg published thirteen previously unknown love letters by Beethoven to Josephine von Brunswick that could be dated to the period between 1804 and 1809/10, when she was a widow after the early death of her first husband, Count Deym. The letters had previously been in the collection of Swiss medical doctor and passionate collector Hans Conrad Bodmer.

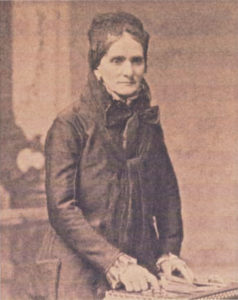

Josephine Brunszvik

The controversy between various investigators has continued, but it has become clear that the immortal beloved was Josephine von Brunswick. Widowed after the death of her first husband, Count Deym, she and Beethoven likely met – however, Beethoven met with resistance from Brunswick’s family about his plans to marry Josephine, as he was a commoner and she an aristocrat. Josephine and her sister, Thérèse, were in Switzerland together with the famous educator Pestalozzi. There she met the Baltic German Baron Christoph von Stackelberg, who become her second husband. The marriage was not happy, although they had three children: Maria Laura, Theophile, and Minona, who has been supposed to be Beethoven’s daughter. One of the few surviving portraits of Minona from her younger age shows a striking resemblance to Beethoven.

Reinvere explains how he came to this subject: “In 2016, I became increasingly interested in Josephine von Brunswick and her pivotal role in Beethoven’s life. She was the woman that Beethoven had been passionately in love with for more than two decades. I think, she was a vital force for Beethoven’s body of work – and her influence is still underrated. When people talk about Beethoven, they mostly talk about Napoleon and Beethoven’s deafness, but he ardently wanted to have a family, longed for marriage, and for children of his own.

I then discovered that Josephine’s daughter Minona lived in Tallinn, the city I was born in, for a long time. And, that she was born exactly 9 months after the famous letter to the immortal beloved, who was Josephine, as 99.99% Beethoven scholars think today. I immediately recognized the potential of creating two really grand female roles, which are torn apart by the idealistic forces of two very ambitious men: Beethoven and Josephine’s husband, Baron von Stackelberg.”

Dora Stock: Amalie Sebald (detail)

When I ask about his views and his research on this exciting topic, Reinvere says: “Minona has been a topic of Beethoven research for almost fifty years. It was the French Beethoven scholars, Jean and Brigitte Massin, who ruled out all addressees of Beethoven’s letter, other than Josephine. In 1977, Swiss Beethoven scholar Harry Goldschmidt wrote his remarkable book Um die Unsterbliche Geliebte (About the Immortal Beloved) in which he reconstructed the probable events in Prague during July 1812. He worked like a profiler or an inspector in a criminal investigation and won high international esteem for his research.”

Most scholars agree that Josephine was Beethoven’s “immortal beloved,” and that there’s a very high probability that Minona was Beethoven’s daughter. Minona’s mother was a Hungarian countess and belonged to the high aristocracy of Vienna. After the death of her first husband, the Bohemian Count Deym, she became a personal friend of the Austrian Emperor who promised to protect her children. Beethoven was her close friend and was also friends with her sister Thérèse and her brother Franz.

Minona von Stackelberg in her youth

“Josephine met Baron Christoph von Stackelberg in Switzerland, where Christoph was a pupil of the famous pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. Christoph became the teacher of her children. Soon, Josephine was pregnant and unwillingly, against the will of her mother and after pressure from Stackelberg, married him. Josephine had no connections to Estonia, but despite that, Stackelberg later took her children with him to his native town Tallinn. Minona lived together with her sister in the Old Town of Tallinn – I actually found out through my own archive work, where, in seclusion, they were kept away from the rest of Stackelberg’s family, spending most of their time practicing piano and learning. Christoph von Stackelberg’s household in Tallinn was a very bitter place to live – Stackelberg was very unhappy with how the things turned out.”

Minona von Stackelberg in her old age

Reinvere is also a recognized essayist and writer and is known as someone, who himself writes the librettos for all his operas. He talks about it: “The most important mentors in my life, Estonian-Swedish pianist and writer Käbi Laretei and her ex-husband, Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, encouraged me twenty years ago to write my own texts. I have learned a lot through them, about one’s personal writing techniques, about storylines, etc. It has been a very natural way for me. The story of Minona is a typical opera story: about the absence of the father. Or – the elusiveness of one’s father, at the same time when children mostly have to pay for the artistic ambitions of their parents. Around this dilemma and the two strong women associated with the two powerful men – I built the story of Minona. I won’t write music – nor even concept, before libretto is mostly finished. But I do have certain musical aims, when constructing my libretto. Librettos have to serve the macro form of opera’s music.”

He explains his opera writing principles: “I think everyone should write differently and there is no standard on how one should write an opera. I myself am mostly interested in a narrative story, where a singing persona is in the focus.”

I asked him about his examples and influences, and whether he would be influenced by Beethoven’s sole opera Fidelio. He says: “I think there are too many to mention. But in Minona, I was not much interested in the storyline of Fidelio as much as I was in the principle of hope – Minona is in a way an anti-Fidelio opera.”

Ia Remmel was born in Tallinn. She graduated at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre with a diploma as a pianist, a piano pedagogue and a chamber musician. Since then she has been active as a piano teacher and a culture journalist. She is currently working in the Estonian music journal as an editor. She regularly writes concert reviews and articles for different newspapers and journals in Estonia and abroad.

Fascinating, stunning research! It’s wonderful to think that Beethoven MIGHT have had a daughter who did show some talent as a composer. But the situation must have been heartbreaking, if indeed she was his. He could never acknowledge her, and Josephine would have been shunned if the truth got out. Perhaps people did notice Minona’s resemblance to Beethoven and gossiped about her anyway. Just one point: the portrait captioned as young Minona is actually of her mother, Josephine von Stackelberg, nee von Brunsvik.

But with the Fore Head, the Eyes and the Nose of Beethoven.

Yes indeed! DNA will likely solve this mystery.

Many thanks for your comments.

We have amended the image accordingly.