One of the most groundbreaking musical happenings of the late 12th century was Pérotin Magnus (Master Pérotin) and his setting of the ‘Viderunt omnes’ text. This 6-line text speaks of God’s relation to the Earth and how all have seen his power:

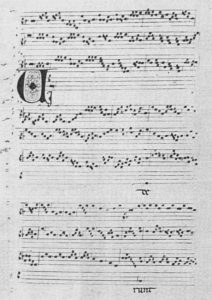

First page of Pérotin’s Viderunt Omnes

Viderunt omnes fines terræ

salutare Dei nostri.

Jubilate Deo, omnis terra.

Notum fecit Dominus salutare suum;

ante conspectum gentium

revelavit justitiam suam.

All the ends of the earth have seen

the salvation of our God.

Rejoice in the Lord, all lands.

The Lord has made known his salvation;

in the sight of the heathen

he has revealed his righteousness.

Its basic setting is quite plain, but the melody is important because it’s the basis for the next two settings.

Anonymous: Viderunt / Viderunt omnes (Ensemble Gilles Binchois; Dominique Vellard, cond.)

The forward-looking composers of the Notre Dame school made 2 different versions of this text. Léonin made a two-part version where the lower voice sings the pre-existing melody and the top voice echoes the lower voice’s actions. In this 1976 performance by the London Early Music Consort, recorded in the early days of the Early Music Revival, the 2 voices are augmented by a bit of percussion and the lower voice is sung by multiple singers. Nonetheless, you can hear the bare-bones structure of the work.

Leonin: Viderunt omnes (James Bowman, counter-tenor; London Early Music Consort; David Munrow, cond.)

Pérotin’s four-voice setting, using what was known as organum quadruplum, is thought to have been written for the Feast of the Circumcision in 1198. The bishop of Paris was promoting the use of multiple voices, i.e., polyphony, and this work would have been absolutely the latest and hottest thing. The use of four voices alone makes it important, but it was Pérotin’s intricate rhythmic details and the very large-scale designs make it unique.

Hilliard Ensemble

The same melody that Léonin used is in the lower voice, and the use of multiple notes per syllable (melisma) makes the text something of only secondary importance. Note in the third line of the Viderunt omnes score how slow the bottom voice is – he holds his notes while all the action goes on above.

In the performance, the setting of the first syllable, ‘Vi-,’ takes a minute, ‘-de’ takes another 30 seconds, and the last syllable, ‘runt,’ finishes at 2 minutes and 30 seconds. Even with a short prayer of only 6 lines and 22 words, this makes for a piece that’s nearly 12 minutes long. This kind of extreme text setting didn’t survive for very long because, in the end, it was always the words that would be more important than the music in the church.

Pérotin: Viderunt Omnes (Hilliard Ensemble)

John Casken

The Hilliard Ensemble’s 1989 recording was an influential recording in getting us to rethink the music of 12th century Paris without the need for extra bells and percussive whistles. It was the music, pure and simple, delivered in a performance that brought it back to life. The 1989 recording was probably a far cry from what was heard in 1198 Paris, as it was informed by another 800 years of performance history, but still could give us an idea of what a truly talented composer of the 12th century was up to. Now, what happens when we move it another 25 years ahead?

English composer John Casken took the Hilliard Ensemble back to the studio in 2014 to make another recording of Pérotin’s ‘Viderunt omnes’ but now with a contemporary ensemble. This isn’t a return to the early days of the Early Music Revival, but the creation of a new piece that not only builds on the original energy of the Pérotin original (and the Hillard’s performance) but also adds its own polyphony to the work.

Pérotin: Viderunt omnes (arr. J. Casken for vocal ensemble) (Hilliard Ensemble; ASKO-Schönberg Ensemble; Clark Rundell, cond.)

The work is a sublime combination of ancient and modern and, as sung by the Hilliard Ensemble and augmented by John Casken, becomes the vision of Pérotin carried from the 12th to the 21st century.