Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

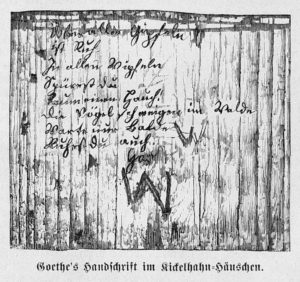

Goethe’s Wandrers Nachtlied II (Über allen Gipfeln) is considered by many to be the most perfect lyric in the German language. The poet is supposed to have written the poem on the evening of 6 September 1780 onto the wall of a lodge on top of the Kickelhahn Mountain near Ilmenau, where he supposedly spent the night.

Over all summits

Is peace,

In all treetops

You feel

Hardly a breath:

The birds are silent in the woods.

Only wait, soon

You too shall rest

Goethehauschen

The poem addresses the transitory nature of life and the search and longing for peace and eternal rest. According to some literary scholars, it simultaneously presents “an optical and organic view of this progression.” The former reading suggests a progression according to physical observation of the changing of the distances from far to near. In the latter, the reader sees a metamorphoses from nature to animal to man. In eight lines of poetry Goethe unites landscape, creation and creature in evening silence while humanity is still restless but expects sleep, death and eternal peace. As has been written numerous times, in eight lines of poetry “Goethe wanders the entire cosmos.”

Franz Schubert: Wandrers Nachtlied II, D. 768 (Matthias Goerne, baritone; Eric Schneider, piano)

Goethe’s Wandrers Nachtlied

Franz Schubert’s setting of Wandrers Nachtlied II was composed in 1823 and is the most renowned musical reading of the poem. Schubert primarily addressed the final release of tension and the arrival of “peace.” His through-composed setting breaks the poem down into three main sections, responding to the progression from nature to animal to human. Predictably, within his reading the piano prelude and postlude play important roles, and although the setting remain in a single key, the composer employs different piano textures to characterize each section. The opening section features homophonic chordal movement, while the use of syncopation in the second main section represents the shift from inanimate nature to a lively and less predictable animal. The homophonic style returns in the end and is extended in a piano postlude to lengthen the anticipation of release. Through skillful text repetition, subtle modulations and changes in the piano texture Schubert created a powerful dramatization of the sense of longing.

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel: Uber allen Gipfeln ist Ruh (Maarten Koningsberger, baritone; Kelvin Grout, piano)

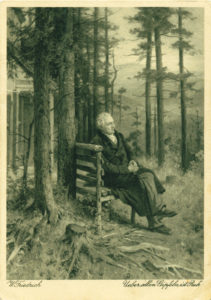

Ilmenau

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel composed her setting of (Über allen Gipfeln) in 1835. Her reading is also divided into three main sections, but Hensel focuses on the rhyme scheme by placing lines 6 and 7 within the same section. To foster a stronger sense of continuity and connection between the first two sections Fanny’s song unfolds as regular cantabile melodies that are colored through chromatic manipulation of the motives. The piano not only provides harmonic support with a rapid harmonic progression, but also takes an active role with a variety of figurations and interplay between melody and accompaniment. The triplet figure in the piano motive generates a strong sense of direction in the music, and as it is used against a duple melody in the voice line, it evokes a sense of unease by obscuring the metric regularity. In the final statement of the poem Hensel uses wandering chord progressions in the piano accompaniment to emphasize the search for peace. Finally, the music arrives at the original key and peace and stability have finally arrived.

Franz Liszt: Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh (Marlis Petersen, soprano; Jendrik Springer, piano)

Franz Liszt brought the rich pianist textures of his keyboard music to his Lied compositions. This allowed him to approach the form and tonal palette of his Lieder in a much more flexible manner. As a result, “his Lieder no longer only cultivate internal emotion through simplicity but also act as a medium of emotional expression to the outside audience.” Liszt was going through a trying time in his life when he composed his setting of Wandrers Nachtlied II in 1848. It is the piano in Liszt’s setting that introduces new melodic materials, and the instrument acts as both accompaniment and independent entity. His setting concludes with the musical material from the beginning, aiming to create a sense of unity. However, the return is subtly varied in terms of texture, dynamics and key. It is the same musical material but expressing a different message. By returning to the music of the opening section, Liszt connects nature to the Wandrer and established an emotional intimacy between nature and humanity. While Liszt focuses on a long dramatization of “Only wait, soon,” Charles Ives builds up to this climax by creating an overall musical contour that spans the entire song. Written during his student days at Yale University in 1901, “Ilmenau” focuses on the promise of fulfilled longing, and he creates tension by changing the meter and an increase in the tempo of the music. Preparing for this climax, the occasional chromatic inflection reminds us that the promise of eternal peace is still unfulfilled.

Franz Liszt brought the rich pianist textures of his keyboard music to his Lied compositions. This allowed him to approach the form and tonal palette of his Lieder in a much more flexible manner. As a result, “his Lieder no longer only cultivate internal emotion through simplicity but also act as a medium of emotional expression to the outside audience.” Liszt was going through a trying time in his life when he composed his setting of Wandrers Nachtlied II in 1848. It is the piano in Liszt’s setting that introduces new melodic materials, and the instrument acts as both accompaniment and independent entity. His setting concludes with the musical material from the beginning, aiming to create a sense of unity. However, the return is subtly varied in terms of texture, dynamics and key. It is the same musical material but expressing a different message. By returning to the music of the opening section, Liszt connects nature to the Wandrer and established an emotional intimacy between nature and humanity. While Liszt focuses on a long dramatization of “Only wait, soon,” Charles Ives builds up to this climax by creating an overall musical contour that spans the entire song. Written during his student days at Yale University in 1901, “Ilmenau” focuses on the promise of fulfilled longing, and he creates tension by changing the meter and an increase in the tempo of the music. Preparing for this climax, the occasional chromatic inflection reminds us that the promise of eternal peace is still unfulfilled.

Charles Ives: Ilmenau (Over all the treetops) (Robert Barefield, baritone; Carolyn Hague, piano)