Friederike Brion

Goethe’s most famous lyric with refrain is undoubtedly “Heidenröslein” (Heath Rose). The poem is a sustained metaphor for the deflowering of a maiden, and it possibly originated during Goethe’s stay in Strasbourg. During his two-year stay, the 21-year-old poet fell in love with Friederike Brion, daughter of the vicar of Sesenheim, a village ten kilometers north of the city. By all accounts, the affair between Friederike and Goethe was rather tumultuous, and while she was under the impression of being engaged, he eventually paid her a farewell visit before returning to his hometown of Frankfurt. Since Friederike’s sister burned all of Goethe’s letters after her death, we will never know exactly what transpired between them, but the strong desires, the mutual wounding, the pain and selfish destruction in the “Heidenröslein” has been called “a summary of the Goethe-Brion love affair.”

A boy saw a rose growing,

A rose upon the heath.

It was so young and morning-fresh,

He quickly ran to look at it up close.

He looed at it with much joy.

Rose, rose, red rose

Rose upon the heath!

The boy said, I’ll pluck you,

Rose upon the heath!

The rose said, I’ll prick you

So that you’ll always think of me,

For I won’t suffer it.

Rose, rose, red rose

Rose upon the heath!

And the savage boy picked

The rose upon the heath;

The rose, defending itself, pricked away,

But its aches and pains availed it not;

It had to suffer all the same.

Rose, rose, red rose

Rose upon the heath!

Johann Friedrich Reichardt: Heidenröslein (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Rudolf Jansen, piano)

Johann Gottfried Herder

The poetry uses very simple vocabulary, and the poetic lines are short. The phrase “Rose upon the heath” is repeated throughout, and the poetic structure reinforces the emerging simplicity of the “Volkslied,” (Folk Song). The Prussian preacher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) posited that concept and suggested that there was no universal human nature and no universal human truth, but that each human society was a unique entity, and uniquely valuable. Each language had a particular way of revealing unique values and ideas that constituted a community’s specific contribution to the treasury of world culture. And it was the explosion of published folklore and its artistic imitations that enhanced the national consciousness of individual societies. Herder published a comparative anthology of folk songs from all countries, and he officially coined the term “Volkslied.” Let’s not forget however, that Herder’s concept applied exclusively to poetry containing no original melodies. Musical setting emerged from a number of distinct traditions, and the Reichardt setting originated with the Berlin circle. This school of composition, much praised by Goethe, advocated the primacy of the poem and the simplicity of the vocal line and of the musical accompaniment.

Franz Schubert: Heidenröslein, D. 257 (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

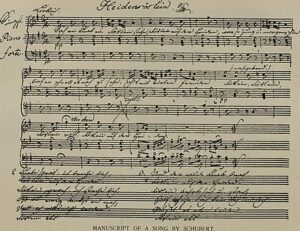

Schubert’s Heidenröslein

While the simplicity of Reichardt’s setting almost deliberately suggests anonymity of authorship, the setting by Franz Schubert does not imitate the folksong tradition. According to scholars, “he creates it or provides an occasion for it.” The simplicity and innocence of Schubert’s music is not born from inexperience, but from a deep familiarity with the ideas and ideals of Goethe. Schubert did sent this setting to the poet in April 1816, but Goethe completely ignored it. Schubert immediately takes us to the outdoors, and the lighthearted vamp between the hands does suggest the carefree young man roaming the countryside. Yet, “the very nature of these chords suggests the demure innocence of the rose, and the curvaceous melody suggest luxurious and alluring beauty.” There is deceptive charm in the short instrumental interludes, and the music alongside the poem works on a number of different levels. Although Schubert’s setting bubbles with merriment, there is a streak of gentle melancholy in the major key that suggests much deeper and more sinister layers of meaning.

Robert Schumann: Romanzen und Balladen I, Op. 67 “Heidenröslein” (Aquarius, choir; Marc Michael de Smet, conductor)

When Schumann’s friend Ferdinand Hiller left Dresden to take up the position as director of music in Düsseldorf in 1847, Schumann inherited an amateur male choir. Amateur choruses and choral societies were all the rage, reinforcing social bonds and community, and reflecting the social and political dynamics of the period. Schumann wrote a number of part songs for his “Liedertafel” (male chorus), but the following year he established a mixed choir counting roughly one hundred amateur singers. Schumann went to work and composed four albums of Romanzen und Balladen for his choral society, which included an SATB setting of Goethe’s “Heidenröslein.” While the strophic nature of Schumann’s setting is no surprise, the chromaticism is striking. Schumann thereby not only highlights the disturbed character of the male protagonist, but also shows empathy for the sad fate of the rose itself. The “Heidenröslein” settings come full circle in the reading by Johannes Brahms, who almost painfully—in his search for authenticity—returns his setting to the child-like simplicity of the Reichardt setting.

Johannes Brahms: 15 Volks-Kinderlieder, WoO 31, No. 6 “Heidenröslein” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Karl Engel, piano)