A Moderated Compendium of Influences

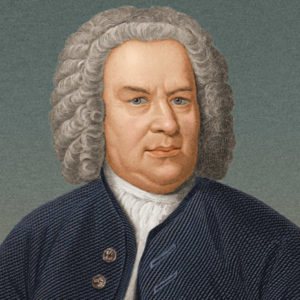

J.S. Bach

© biography.com

One of the most laborious tasks for an artist; listing, comparing and rating other artists or their works. Deciding which to prefer and which to reject, which is more important and which is less. There is so much diversity in music, that it is often very difficult for a musician to make a choice. Had I been asked to pick my favourite artists, I would have decided not to compile a list — which as soon as written would have lost its value — but rather select a handful of musicians that have profoundly influenced my musical direction. For the past ten years, chronologically…

…Let’s start where it should start. Bach and The Goldberg Variations. Of course, so much has been said about Bach — and I have said quite a bit about him too. He has written pretty much all the grammar of classical music, and it is difficult to avoid him. The Goldbergs were essential as they forecasted the nocturne genre; Chopin, Satie and everyone that came after until today’s indie classical composers. Bach’s music is also very minimalistic and resonates a lot with my own perception of music.

Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (Glenn Gould, piano)

Schubert

© Seattle Choral Company

I am fascinated by Schubert. The German composer has excelled at combining musical interest and musical beauty; the manner he treats the melody — always at the forefront of his works — and how he integrates harmonic diversity and audacity is remarkable. Schubert was writing modern music before it even existed and forecasted a century of music. I often go back to his “Piano Sonata D. 959” — actually the last three — and pick inspiration from it here and there, whether in the structures or the musical language.

Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 20 in A Major, D. 959 (Murray Perahia, piano)

Mendelssohn

©Wikipedia

Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte — particularly the “Venezianisches Gondellied” — have been essential in teaching me how to combine the world of popular music with the one of classical. Mendelssohn is writing popular music through the medium of serious music; the pieces are simple, yet diverse and rich, and most importantly memorable. Modern composers who approach serious music in a similar way owe a lot to him. Through his music, I have learned how to be a songwriter as much as a composer.

Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte, Book 2, Op. 30: No. 12 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 30, No. 6, MWV U110, “Venezianisches Gondellied” (Murray Perahia, piano)

If Bach wrote most of the musical grammar used over the last couple of centuries, Chopin wrote the (piano) vocabulary of classical music — with a little help from Beethoven too. To me, he has been significant in learning how to write for the keyboard. There is everything you can think of in his music — a diversity in all the musical elements — and he is everywhere in other people’s works. Chopin’s approach to composing music is essentially painting with sounds; his “Prelude #15”, also known as the “Raindrop” speaks for itself.

Chopin: 24 Preludes, Op. 28 – No. 15 in D-Flat Major, “Raindrop” (Maurizio Pollini, piano)

© www.stgilesmusic.co.uk

Listening to Tchaikovsky is equal to travelling through the vastness of Russia and picturing its diverse cultures. The composer has embraced his national identity and it reflects in his music. This could not be better expressed than in his “Concerto for Violin and Orchestra”. To quote one of my previous articles Three Shades of Yellow: “This piece has always brought clear images of bright red to my mind. Of course there is the association with Russia, and its strong historical connection to red; but I feel that on top of that, the concerto expresses all the feelings, passion, tenderness and strength of the Russian culture.”

Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 (Isaac Stern, violin; Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

Satie always resonates with me a lot. I find many common grounds with him, and his most important musical advice is that — in the absolute — technical proficiency is not as important as musical identity; being original. Regardless of the technical abilities an artist should use his weaknesses as much as his strengths to form his musical personality. For me — who never quite fitted into traditional education systems — that was very important. Of course, listening to “Gnossienne 1” illustrates very well this argument.

Stravinksy. I have always been interested him; perhaps him even more than his music. When I discovered The Rite of Spring, it was from a jazz perspective and the one of an improviser rather than a composer. The use of rhythm, the harmony, the dissonance, the consonance, the dynamics; to me it all related to improvisation. His music sits between aggressiveness and sweetness, agreeable and unpleasant, comfort and discomfort. Stravinsky made everyone revise their approach to music and ignited the flame of modern classical music.

With Pärt it is all about silence. The Estonian composer teaches to listen; to listen to the music, to listen to the sounds, and to listen to the sounds between the sounds. Thanks to him, I have learned to pay more importance to the elements that I am choosing and the ones that I am not choosing. Just like there is black and there is white, there is sound and there is silence. And simplicity too, that is for “Spiegel im Spiegel”. Pärt has also helped me realise that I should treat my music in the most scared way possible.

Pärt: Spiegel im Spiegel (Vadim Gluzman, violin; Angela Yoffe, piano)

Philip Glass

© blog.sonos.com

If Chopin wrote most of the piano vocabulary book then Glass wrote the one of minimalism — and is responsible for most of my earlier one. With Metamorphosis, the American composer provided a bridge between my own musical experience — the one of popular music — and where I wanted to grow and go — somewhere above that. The simplicity of his music resonated with the influences I had, and gave me a starting point to create my own language. The life of the composer is also very influential to me and is a great lesson for any aspiring composer.

Glass: Metamorphosis II (Philip Glass, piano)

Richter, has been the trigger to my ambition in becoming a music composer. While Glass was my first bridge between my past and future musical experiences, Richter taught me how to create music that reflected the period I was born in, embracing its modernity and its heritage. A lot of my approach to developing projects is led by his works, and he is a constant inspiration to me. “H in New England” — from 24 Postcards in Full Colour — is of course a very good starting point to discover the German-born British composer.

As I was writing this article, names and titles kept coming up, as well as the regrets of not having selected them. Although it is a very small selection, there is a plethora of influences that I have unconsciously integrated and which emerges with time. In the hope of musical growth, it seems necessary to reject some current and past influences. In order not to be stuck in one place, it seems necessary to accept the traditions and heritage, and to use them in order to move forward. Each artist and each art piece is a door to another world of discoveries, that never stops.