Viruses have apparently plagued the Earth for several billion years. According to some virologists “Viruses are as old as life itself, if not older.” For some reason, however, COVID-19 seems to be the most dangerous virus to date. This has nothing to do with the virulence of COVID-19, but with anxiety, panic, hatred and racism generated by the social media herd. Instead of getting professional information from experts at the CDC and WHO, so-called herd intelligence is fueling a huge range of fake news, conspiracy theories and hoaxes that is now called an “infodemic.” Who needs professionals when you can listen to Muppets with zillions of likes instead? Everybody is entitled to have a personal opinion, but a zillion opinions do not equal a single scientific fact!

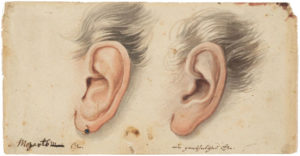

“Mozart’s ear”

The way to address the personal emotional turmoil generated by this latest viral pandemic is to gather information from expert professionals that have spent their entire lives and careers becoming the best of the best within their discipline. In this time of uncertainty and great disruption to our personal and professional lives, we need to calmly educate ourselves in order to separate fact from fiction. And for me personally, there is no better way to calm down and escape the rabid pessimism and fakery surrounding COVID-19 than to listen to a Mozart Piano Concerto. For Mozart, there was always light at the end of the tunnel, and he optimistically believed in an enlightened shared humanity.

Portrait of Franz Schubert by Gabor Melegh

Contrary to popular opinion, Mozart was not an exceptionally ill child, and as an adult he generally enjoyed good health. He did experience a life-threatening illness at the age of 9, which was probably typhoid fever. On the left-hand side he had what has since become known as “Mozart’s ear,” a pinna with under-development of the antihelical fold. He did suffer from frequent attacks of tonsillitis, and in 1784 he developed post-streptococcal Schönlein-Henoch syndrome, which caused chronic glomerular nephritis and chronic renal failure. His death certificate shows “hitsiges Frieselfieber,” one of many infectious diseases prevalent at that time, but according to a recent hypothesis, Mozart’s might actually have died from Trichinosis. For much of his short life, Franz Schubert suffered from cyclothymia, a mental illness that resulted in severe mood swings that fluctuated between hypomanic and depressive episodes. His condition became far more extreme during his mid-twenties, and his friends reported periods of dark despair and violent anger. With all the psychological dangers posed by COVID-19, we can certainly empathize with Schubert and celebrate the enormous range and emotional depth of his art.

Franz Schubert: Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 114, D. 667, “The Trout” (Hagen Quartet; Alois Posch, double bass; András Schiff, piano)

Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy struggled with ill health throughout his life, yet his musical imagination was as healthy and fertile as can be. Each of the movements of his Nocturnes evokes a specific landscape and each is a masterpiece of sensual orchestration. As Debussy writes, “Nuages renders the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in gray tones lightly tinged with white. Fêtes gives us the vibrating, dancing rhythm of the atmosphere with sudden flashes of light. There is also the episode of the procession (a dazzling fantastic vision), which passes through the festive scene and becomes merged with it. But the background remains persistently the same: the festival with its blending of music and luminous dust participating in the cosmic rhythm. Sirènes depicts the sea and its countless rhythms and presently, amongst the waves silvered by the moonlight, is heard the mysterious song of the Sirens as they laugh and pass on.”

Claude Debussy: Nocturnes (Cleveland Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Bach Family

In times of uncertainty and turmoil we turn to family for emotional and other support. And in musical terms, that means turning to the Bach family. Throughout the misery of the Thirty Years’ War, this group of over 50 known musicians and notable composers produced exceptional and enduring music. The Bach family never left the area of Thuringia until the sons of Johann Sebastian went afield to conquer the more modern world. As one of the J.S. Bach’s earliest biographer’s wrote, “Johann Sebastian Bach belongs to a family whose love and skill in music appear as though they were universal gifts granted by nature to all its members. So much is certain, that from Veit Bach, the ancestor of the family, all his descendants, now down to the seventh generation, have devoted themselves to music, and all of them, with perhaps a few exceptions, have made it their profession.” Fortunately, we can always count on the support of the Bach family in times of need and trouble, and as you listen to some delightful concertos please stay healthy in body and in spirit.

J.C. Bach: Symphonie concertante in A Major, W. C34 (Stephan Schardt, violin; Joachim Fiedler, cello; Cologne Musica Antiqua; Reinhard Goebel, cond.)

W.F. Bach: Flute Concerto in D Major (Verena Fischer, flute; Cologne Musica Antiqua; Reinhard Goebel, cond.)

J.C.F. Bach: Concerto for Viola and Piano in E-Flat Major, B. C44 (Reinhard Goebel, viola/cond.; Robert Hill, harpsichord; Cologne Musica Antiqua)

C.P.E. Bach: Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano in E-Flat Major, Wq. 47, H. 479 (Leon Berben, fortepiano; Robert Hill, harpsichord; Cologne Musica Antiqua; Reinhard Goebel, cond.)