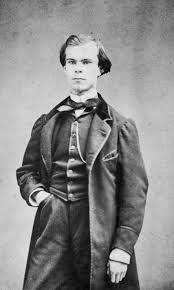

Paul Verlaine

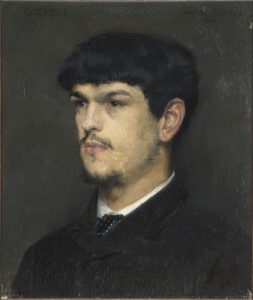

In 1911 Claude Debussy was questioned in the journal “Musica” on the ideal text to set to music. Having skeptically illustrated a number of possibilities, the composer declared his preference for rhythmic prose, adding that the composer himself should write his own text. To be sure, Debussy did set several of his own texts to music, but of the 56 songs he published no fewer than 18 set poems by Paul Verlaine.

The aesthetic kinship between Verlaine and Debussy has been amply discussed, with the composer taking Verlaine’s dictum “Music before all else, and for that chose the irregular, vague and melting better into the air” and made it a literary reality. Debussy took two stabs at Clair de Lune, with the first setting dating between 1882 and 1884, before his visit to Rome or an acquaintance with the music of Wagner.

Your soul is a chosen landscape

Where charming masquerades and dancers are promenading,

Playing the lute and dancing, and almost

Sad beneath their fantastic disguises.

While singing in a minor key

Of victorious love, and the pleasant life

They seem not to believe in their own happiness

And their song blends with the moonlight,

With the sad and beautiful moonlight,

Which sets the birds in the trees dreaming,

And makes the fountains sob with ecstasy,

The slender water streams among the marble statues.

Claude Debussy: Clair de lune (1882) (Veronique Dietschy, soprano; Emmanuel Strosser, piano)

Claude Debussy

Clair de lune conjures up a magical moonlit world in which commedia dell’ arte figures linger without clear purpose, but “with a sharp eye for heir decorative possibilities.” It is the epitome of that dream world in which sense is abandoned before the senses, no loved one is addressed and no story told. However, there is a clear subtext to this particular setting. The 18-year old Debussy was the accompanist for Mme Moreau-Sainti, a professional singer who had opened a singing school for the ladies of Parisian high society. And thus his gaze fell upon a red-haired beauty with green eyes, blessed with a beautiful high soprano voice. As his passion grew, Debussy wrote songs that resembled an amorous diary of dreams and desires of infinite sweetness. In all, Debussy composed around forty songs for Madame Vasnier, and when he left for Rome he assembled thirteen in a bound album and added the following dedication. “To Mme Vasnier, these songs which have lived only through her, and whose enchanting grace would be lost if they no longer passed through her fairylike melodious lips,”

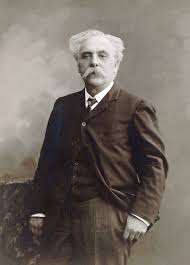

Gabriel Fauré

When Debussy fashioned his second setting of Claire de lune in 1892, he had fundamentally transformed his compositional technique. His approach to Verlaine’s poetry had certainly matured and become more sophisticated, sensitive and unique. Verlaine’s poetry chiefly focuses on small, intimate beauties, often related to nature and love. As such, it mirrored the artistic ideals that developed in Debussy’s music during this time. Debussy’s approach to Verlaine became increasingly less that of a composer taking words and using them to creating music, but more so a composer allowing the poem to define his music. As Verlaine tellingly suggested, “Music is not the beauty of song, but song the beauty of music” It has been proposed that without Verlaine, Debussy would never had developed such a varied and sensitive approach to writing songs. Let us not forget, however, that Verlaine and Claire de lune also inspired the famous Suite bergamasque with “Clair de lune” dutifully emerging in the third movement.

Gabriel Fauré: Clair de lune, Op. 46, No. 2 (Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Jérôme Ducros, piano)

Joseph Szulc

The beauty of Verlaine’s language appealed to a wide spread of French tastes, notably to composers both from the Schola Cantorum, run by Vincent d’Indy, and from its rival, the Paris Conservatoire. Gabriel Fauré set the poem to music in 1887 in a version for voice and piano. At the instigation of the Princesse de Polignac, he subsequently made a version for voice and orchestra. Fauré’s setting of the poem takes a different approach to Debussy, foregrounding a piano theme into which the vocal line fits comfortably and, likewise, without any pyrotechnics.

The 1907 setting by Joseph Szulc, a Polish composer who studied with Massenet and went on to write successful musical comedies, copies his predecessors in varying the vocal rhythms between duplets and triplets and, “after the hitherto unbroken piano semiquavers, tellingly paints ‘extase’ by slowing briefly into quavers.”

Josef Zygmunt Szulc: Clair de lune Op. 83, No. 1 (Carolyn Sampson, soprano; Joseph Middleton, piano)