Mathilde Mauté de Fleurville

The twenty-one poems published in La Bonne Chanson by Paul Verlaine are addressed to sixteen-year-old Mathilde Mauté de Fleurville. She came from a respectably bourgeois background, and the family had somehow amassed a fortune. They owned a small hotel and garden in a quiet street in Montmartre, and Madame Mauté de Fleurville prided herself on rubbing shoulders with artists and composers. Her son by her first marriage was a composer of light music, and in 1871 the young Claude Debussy was her student. She thought of herself as a patron of the arts, but she wasn’t thrilled when Verlaine came calling for the hand of her daughter.

Mathilde was painfully innocent, and initially she wasn’t interested. However, as she recalled later, “he became gentle and radiant when he was around me, and at that moment he ceased to be ugly… and love transformed the Beast into Prince Charming.” Verlaine managed to win Mathilde’s favor, and Madame Mauté de Fleurville was thrilled that the poet was highly spoken of in the best literary circles of the day. They lived with her parents and soon enough had a little boy. The poems in La Bonne Chanson as such, are a proclamation of love.

Mathilde was painfully innocent, and initially she wasn’t interested. However, as she recalled later, “he became gentle and radiant when he was around me, and at that moment he ceased to be ugly… and love transformed the Beast into Prince Charming.” Verlaine managed to win Mathilde’s favor, and Madame Mauté de Fleurville was thrilled that the poet was highly spoken of in the best literary circles of the day. They lived with her parents and soon enough had a little boy. The poems in La Bonne Chanson as such, are a proclamation of love.

Jules Massenet: Revons c’est l’heure (Philippe Jaroussky, counter-tenor; Nathalie Stutzmann, contralto; Jérôme Ducros, piano)

Paul Verlaine

In essence, La bonne chanson is an expression of the happiness that Verlaine had expected to find in his marriage with Mathilde. Verlaine was an extremely gentle and sensitive poet with a distinctive tone and a remarkable musicality. He longed for a simple and quiet life, and his poems are full of confidential lyricism, replete with nuances, and with words chosen for their simplicity and subtle sonorities. However, he was also a homicidal alcoholic. He drank so much that he soon succumbed to a special form of crazy and violent alcoholism. These two aspects of his character would sometimes violently compete with each other, and he would always be susceptible to one impulse or the other. The lyrical collection in La bonne chanson contains poems about their first meeting, the first period without Mathilde, and his approaching marriage. In the third poem he compares Mathilde’s cheerful voice to music that drives away melancholy. And in the last poem he describes the coming of spring, which brings a cheerful atmosphere even to the diseased city of Paris.

Gabriel Fauré: La bonne Chanson, Op. 61 – No. 3. La lune blanche luit dans les bois (Carolyn Sampson, soprano; Joseph Middleton, piano)

The moon, white,

Shines in the trees:

From each bright

Branch a voice flees

Beneath leaves that move,

O well-beloved.

The pools reflect

A mirror’s depth,

The silhouette

Of willows’ wet

Black where the wind weeps…

Let us dream, time sleeps.

It seems a vast, soothing,

Tender balm

Is falling

From heaven’s calm

Empurpled by a star…

It’s the exquisite hour.

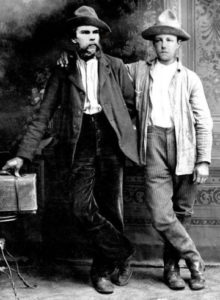

Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud

The calm of the moonlit night did not last, however. For one, Verlaine had lost his position at the city council, and he did receive a letter from the 16 year-old Arthur Rimbaud, who wanted to present his works. Verlaine was fascinated by the poems, and Rimbaud presented himself at the Verlaine residence. Verlaine recalled, “The man was tall, well built, almost athletic, with the perfectly oval face of an angel in exile, with unruly light chestnut hair and eyes of a disquieting blue… He had a real baby’s head, plump and fresh on top of a big bony body with the awkwardness of an adolescent who has grown too quickly.”

Josef Szulc: La lune blanche (Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; David Zobel, piano)

Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud

Madame Mauté de Fleurville and Mathilde were less than thrilled at having Rimbaud as a houseguest. He regaled in nude sunbathing outside the house, mutilated an heirloom crucifix and proudly counted the lice in his long hair. Verlaine plunged into an uninhibited love affair with Rimbaud, a relationship characterized by excesses of alcohol, drugs, and violence. And it was Mathilde and their son who suffered most. One day Mathilde refused to give Verlaine money for drink, so he sized their three-month-old son and flung him against the wall. From that point onwards, he regularly chocked and severely beat his wife. The Verlaine-Rimbaud affair lasted for a full three years and ended tumultuously when Verlaine shot his lover in the heat of passion. Although the shooting resulted only in a minor wrist injury, Verlaine was sent to prison for two years.

Verlaine would be known in his life as a brutal husband and an impious wretch, but as a writer “he became the greatest Catholic poet in the French language.”

Charles Bordes: La bonne chanson (Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; David Zobel, piano)