Self-portrait of Raphael, aged approximately 23

500 years ago, on 6 April 1520, one of the greatest painters and architects of the High Renaissance died suddenly at the age of 37. Raffaello Santi, better known simply as Raphael, hailed from the Italian town of Urbino, a center of humanist learning east of Florence. His father was one of the court painters, as well as a prolific poet.

Raphael: La fornarina, 1518-19

Unsettled by his father’s death in 1494, young Raphael went to Perugia as an apprentice to the painter Perugino. His talents were quickly recognized, and he was given the following introductory letter to the holder of the prestigious communal office in Florence. “The bearer of this will be bound to be Raffaele, painter of Urbino, who, being greatly gifted in his profession, has determined to spend some time in Florence to study… He is a sensible and well-mannered young man, and I bear him great love.” And what an education it turned out to be, as the city of Florence was residence to both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo at that time.

Anonymous: Chiara fontana-Laude e grazie-J’ay pris amours (Ensemble Unicorn)

Raphael: Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1506

While in Florence, Raphael painted a good many Madonnas in a style that became synonymous with his name. In his Madonna of the Meadow, Raphael arranged his figures in a pyramid configuration to create a believable and balanced space. This geometrical device, already popularized by Leonardo da Vinci, agreed with the preoccupation of the Renaissance to rationally order composition. But more important is Raphael’s arrangement of shapes, and particularly his unmistakable modeling of the human form. There is genuine sweetness and warmth conveyed by the faces, and the head of the Madonna is peaceful and luminous. At the same time, the infant Christ and Saint John convey a more playful mood, and the “human quality of the divine figure is Raphael’s trademark.” In 1508, Raphael left Florence for Rome and was quickly employed by Pope Julius II.

Josquin des Prez: Missa de Beata Virgine (Tallis Scholars; Phillips Peter, cond.)

Raphael: The Sistine Madonna, 1512

The pope commissioned him to decorate various rooms of his palace, and Raphael held assorted administrative posts for the papacy. Raphael was running a large and highly successful workshop, with roughly fifty painters under his command. Unlike Michelangelo’s workshop, which was jealously and suspiciously guarded by the master, Raphael seemed to have possessed a remarkably sweet nature. A friend and colleague wrote, “He is so full of kindness and so brimming with charity that the very animals honored him.”

One of his most outstanding works, one that defines the 16th century Renaissance in Rome, is a large fresco executed between 1509 and 1511. Called the “School of Athens,” the fresco is a highly symbolic homage to the great philosophers of antiquity, inspired by the impressive mosaics in Roman baths and basilicas. In the center we find the greatest ancient Greek philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, surrounded by other great figures of antiquity. Raphael’s sensitivity to ordered space, in complete agreement with Classical ideals, and a love for intellectual clarity is also pristinely reflected in the music of his time.

Giovanni Palestrina: Stabat mater (Clare College Choir, Cambridge; Timothy Brown, cond.)

Raphael: The School of Athens, 1509-11

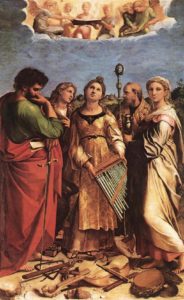

Raphael: The St. Cecilia Altarpiece, 1516-17

Raphael painted St. Cecilia for Cardinal Lorenzo Pucci in 1517. It is his first painting of Cecilia that paired her with musical instruments. With this painting, Raphael solidified St. Cecilia as the Patroness saint of music. As Percy Shelly wrote in 1899, “The central figure, St. Cecilia, seems rapt in such inspiration as produced her image in the painter’s mind; her deep, dark, eloquent eyes lifted up; her chestnut hair flung back from her forehead — she holds an organ in her hands — her countenance, as it were, calmed by the depth of its passion and rapture, and penetrated throughout with the warm and radiant light of life. She is listening to the music of heaven, and, as I imagine, has just ceased to sing, for the four figures that surround her evidently point, by their attitudes, towards her; particularly St. John, who, with a tender yet impassioned gesture, bends his countenance towards her, languid with the depth of emotion. At her feet lie various instruments of music, broken and unstrung.”

Raphael: The Transfiguration, 1516–20

Raphael was highly admired by his contemporaries, and “of all the great Renaissance masters, Raphael’s influence is the most continuous.” We are told, “Raphael died through “continuing his amorous pleasures to an inordinate degree.” Apparently, the painter allowed doctors to bleed him for a supposed chill, when he was simply exhausted with debauchery. Be that as it may, in his 1894 opera Raphael, Anton Arensky primarily focuses on the artistic accomplishments of one of the most creative and artistic minds in Western culture.

Anton Arensky: Raphael, Op. 37 (Marina Domashenko, mezzo-soprano; Tatiana Pavlovskaya, soprano; Alexander Vinogradov, bass; Vsevolod Grivnov, tenor; Russia Spiritual Revival Choir; Philharmonia of Russia; Constantine Orbelian, cond.)