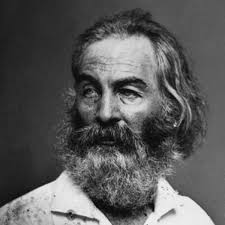

Walt Whitman, year 1855

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) has been called “America’s poet,” and he is considered the father—not the inventor—of free verse. One of the most influential bards, he produced literature of timelessness that appealed to the American idea of democracy and equality. Believing in a vital and symbiotic relationship between the poet and society, he wrote in 1855 “the proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” However, then as now, his work was and is controversial as he deals with death, sexuality, including homosexuality and prostitution, and a brand of nationalism that is currently seen as “arrogant, expansionist, hierarchical, racist and exclusive.” His poetry collection Leaves of Grass delights in sensual pleasures, and it was already highly controversial during its time.

What think you I take my pen in hand to record?

The battle-ship, perfect-model’d, majestic,

that I saw pass the offing today under full sail?

The splendors of the past day?

or the splendor of the night that envelops me?

Or the vaunted glory and growth of the great city spread around me?—no;

But I record of two simple men I saw today on the pier in the midst of the crowd,

Parting, the parting of dear friends,

The one to remain hung on the other’s neck and passionately kiss’ed him

While the one to depart tightly prest the one to remain in his arms.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Leaves of Grass, Op. 89b – No. 1. What Think You I Take My Pen in Hand? (Salvatore Champagne, tenor; Howard Lubin, piano)

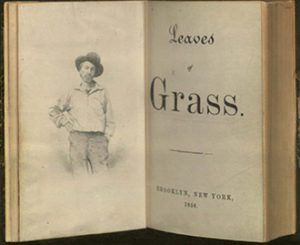

“Leaves of Grass” 2nd edition, 1856

Whitman experimented with a variety of popular literary genres, but in the early 1850s he began writing a collection of poetry that would become Leaves of Grass. His intention was to write a distinctly American epic using free verse “with a cadence based on the Bible.” The first edition was published in 1855, but he would continue editing and revising the collection until his death. In over four decades, the first edition of twelve poems grew to a compilation of over 400. Nevertheless, the poems are loosely connected and represent Whitman’s celebration of his philosophy of life and humanity. He famously proclaimed his poetry to be “Nature without check with original energy,” and described himself as “an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, disorderly, fleshly, and sensual, no sentimentalist, no stander above men or women or apart from them, no more modest than immodest.” When the first edition was published, Whitman was fired from his job as his boss found the poems offensive.

Anthony Holland: New England Poems – III. Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass” (Anthony Holland, narrator; Norman Thibodeau, flute; Danielle Bruce, percussion)

Walt Whitman

The first edition of Leaves of Grass was widely distributed and received significant interest. Fellow poet Ralph Waldo Emerson spoke highly of the work, while John Greenleaf Whittier was said to have thrown his 1855 edition into the fire. “It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass,” commented Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “only that he did not burn it afterwards.” The book was called trashy, profane and obscene, and the author called “a pretentious ass.” And as one of the earliest public accusations of Whitman’s homosexuality, Rufus Wilmot Griswold accused Whitman of being “guilty of that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians.” The controversy surrounding Leaves of Grass generated a good deal of publicity, and Whitman firmly believed that he would be embraced by the working classes. Since he edited, revised and republished Leaves of Grass many times before his death, his focus and ideas were not static. Critics have identified three major thematic drifts, ranging from expressions of love in its sensuous form and sober and melancholy reflections to thoughts of death and immortality.

Dexter Morrill: Roxbury Preludes – No. 5 Leaves of Grass (Pamela Jordan, soprano; Dexter Morrill, tape; Tremont String Quartet)

Since Leaves of Grass represents one of the most important collections of American poetry, it has been widely discussed and interpreted. Naturally, it has been adopted by various groups and movements to further their own personal, political, and social purposes. Be that as it may, Whitman’s exploration and discussion of his own self, his eulogizing of democracy and the American nation, and his poetic expressions of life’s great mysteries has infiltrated popular culture and has been recognized as one of the central works of American poetry.

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated

Mark’d how to explore the vacant, vast surrounding

It launched forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them

And you O my soul where you stand

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing

seeking the spheres to connect them

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul

Matthew Wittall: Leaves of Grass, Book II, No. 7 A noiseless patient spider (Risto-Matti Marin, piano)