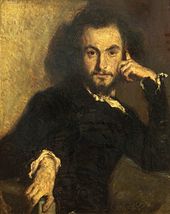

Charles Baudelaire

When Charles Baudelaire published his collection of poems entitled Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) in 1857, he shocked an entire generation. “Candor and goodness are disgusting,” he wrote in the epilogue, describing his masterpiece instead as a “nice firework of monstrosities.”

If rape, poison, dagger and fire,

Have still not embroidered their pleasant designs

On the banal canvas of our pitiable destinies,

It’s because our soul, alas, is not bold enough!

Among poems dealing with decadence and eroticism, “L’invitation au Voyage” lacks the grotesque imageries of the real world. The poet invites his mistress to dream of another, exotic world, where they could live together.

Baudelaire’sLes Fleurs du Mal

My child, my sister,

think of the sweetness

of going there to live together!

To love at leisure,

to love and to die

in a country that is the image of you!

The misty suns

of those changeable skies

have for me the same

mysterious charm

as your fickle eyes

shining through their tears.

There, all is harmony and beauty,

luxury, calm and delight.

Henri Duparc: L’invitation au voyage (Giorgos Kanaris, baritone; Thomas Wise, piano)

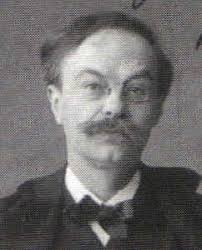

Henri Duparc

As with much of Baudelaire’s poetry, however, the dream maintains a vague sense of nightmare. It presents a sequence of flashing images without meaning, and a cloud of symbols with no system. “His lover is crying and her eyes look treacherous to him, their mystery shadowing the sunlight of his dreaming. The refrain will succeed only in part in restoring a peaceful atmosphere: the reader already knows that it’s nothing more than an illusion.”

Gleaming furniture

polished by age

would decorate our bedroom;

the rarest of flowers

would mingle their fragrance

with the vague scent of amber;

the rich ceilings,

the deep mirrors,

the splendor of the Orient –

everything there

would speak in secret

the soul’s soft native tongue.

There, all is harmony and beauty,

luxury, calm and delight.

Emmanuel Chabrier: L’invitation au voyage (Mary Bevan, soprano; Amy Harman, bassoon; Joseph Middleton, piano)

Emmanuel Chabrier

The dream confuses the souvenirs of the poet’s childhood with the only golden period of Baudelaire’s life. Furniture and flowers recall the life of his comfortable childhood, which was taken away by his father’s death. It contrasts sharply with his current life of a poor poet, who eventually had to go to court to defend against the charge that his collection was in contempt of the laws that safeguard religion and morality.

Alphons Diepenbrock

In 1841, his stepfather had sent him on a voyage to Calcutta, India, in hopes that the young poet would manage to get his worldly habits in order. The trip provided strong impressions of the sea, sailing, and exotic ports, which he later employed in his poetry. The sense of “oriental splendor” is a recurring theme in many Baudelaire’s poems, and his Indian voyage provided an obsession of exotic places and beautiful women. In “L’invitation au voyage” these two elements combine in one photograph, one single dream of perfect happiness.

Alphons Diepenbrock: L’invitation au Voyage (Christa Pfeiler, mezzo-soprano; Rudolf Jansen, piano)

See how those ships,

nomads by nature,

are slumbering in the canals.

To gratify

your every desire

they have come from the ends of the earth.

The westering suns

clothe the fields,

the canals, and the town

with reddish-orange and gold.

The world falls asleep

bathed in warmth and light.

There, all is harmony and beauty,

luxury, calm and delight.

Hans Gefors

In the final stanza the dream reaches its resounding triumph. Vessels come from the ends of the earth to satisfy the desires of the poet’s mistress, and she is not crying anymore. The light of the setting sun turns everything golden and glorious, and the real world falls asleep. When night approaches, the dreamers achieve some real peace and they can live the beauty denied by reality. As Baudelaire tellingly writes, “how mysterious is imagination, the Queen of the Faculties.”

Hans Gefors: L’invitation au voyage (Brigitta Svenden, mezzo-soprano; Nils-Erik Sparf, violin; Mats Bergström, cond.)

I have always loved this poem for its sound in French and for its imagery. For me, the imagery suggests a kind of life in death, or death in life, corresponding to Elysium.

Who was this mistress? An imaginary woman or was there a particular person in his mind whom he is referring as ‘sister’ in this poem?