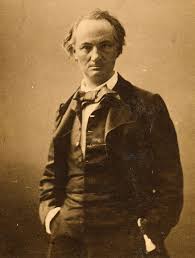

Charles Baudelaire

Setting the poetry of Baudelaire to music is a highly complex undertaking. His poems have a complexity of thought and a richness of verbal music that almost defy the composer to add anything. Francis Poulenc, who devoured Baudelaire’s verse avidly as a young man, never set a word of him, nor did Maurice Ravel. Claude Debussy had just returned to Paris from “two years of internment” in Rome, and he drifted through personal, financial and musical insecurities. His return to Paris brought him into contact with the music of Wagner, and like a good many composers at the time, he made a pilgrimage to Bayreuth. He listened to Parsifal and Meistersinger, and eventually Tristan. Intimately familiar with the poetry of Baudelaire, he suddenly realized that understatement and elegance was the last thing these poems needed. Instead, his song cycle Cinq poèmes de Baudelaire is musically bathed in an almost decadent opulence.

Claude Debussy: 5 Poems de Charles Baudelaire – No. 1. Le balcon (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; James Levine, piano)

Claude Debussy: 5 Poems de Charles Baudelaire – No. 2. Harmonie du soir (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; James Levine, piano)

Claude Debussy: 5 Poems de Charles Baudelaire – No. 3. Le jet d’eau (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; James Levine, piano)

Claude Debussy

The musical mood of the opening “Le balcon” and “Harmonie du soir” takes its clue from the almost self-contained lines of the poems. Debussy closely follows the text by given the repeated line the same contour as the first while altering the pitch and underlying harmony. Essentially, this is mature Debussy already as he had absorbed Wagnerian elements into his own style, with a piano writing that is clearer and much cleaner. The central “Le jet d’eau” stands in marked contrast to its surroundings. Perhaps Debussy felt some respite was needed from the Wagnerian fumes. In many passages we can hear the light and airy atmosphere that will inform much of Debussy’s later writings. Water figuration in the piano permeate the whole song, and Debussy gives the singer the same music for each refrain, again with differences in the piano part.

Your pretty eyes are tired, poor darling!

Keeping them closed, stay a long time still

in that nonchalant pose

in which pleasure came upon you.

Out in the courtyard the chattering fountain

never silent night or day

is gently prolonging the ecstasy

into which love has plunged me this evening.

The water-sheaf which waves

to and fro its thousand flowers,

and through which the moon

shines its pallid rays,

falls like a shower

of large teardrops.

Even so your soul, set ablaze

by the burning flash of pleasure,

leaps up, rapid and bold,

towards the vast enchanted skies.

And then it spills, dying,

in a wave of sad languor

down an invisible slope

into the depths of my heart.

Oh beloved, whom night makes so beautiful,

as I lean over your breasts, I find it sweet

to listen to the eternal lament

that sobs in the fountain-basins!

Oh moon, sounds of water, blessed night,

oh trees trembling all around,

your pure melancholy

is the mirror of my love.

Claude Debussy: 5 Poems de Charles Baudelaire – No. 4. Recueillement (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; James Levine, piano)

Claude Debussy: 5 Poems de Charles Baudelaire – No. 5. La mort des amants (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; James Levine, piano)

“Recueillement” and “La mort des amants” once again return us to the plush world of Wagnerian harmonies. Debussy seemed to have understood that his future lay in combining Wagner with his “peculiarly sensitive sensuousness of the French tradition.”

Louis Vierne

Debussy, as I previously mentioned, composed his 5 Baudelaire setting during a period of intense personal crisis. The same is true of Louis Vierne’s “Five Baudelaire songs,” which emerged between 1917 and 1919, during a time of international upheaval. Vierne took a four-year leave from his tenure as organist at Notre-Dame to recover from problems associated with his blindness, and to mourn the loss of his brother Réné and his eldest son Jacques, who had died during the 1916 campaigns. Vierne’s cycle, based on selections from the posthumous edition of Les Fleurs du mal, opens where Debussy had left off, with “Recueillement.”

It is tempting to read the selected poems as a progression on themes of loneliness, suffering, despair, and death, but it has also been argued that “coherence is derived less from the textual-thematic content and more from the way in which Vierne establishes subtly demanding relationships between the piano and vocal lines.” Unlike Debussy, Vierne does not disrupt the poetic line but keeps the vocal line largely independent of the piano. As a result, the bond between poem and music is exceedingly weak, as it is possible to recover the poem intact from the song score. “As complex mélodies, the lack of interference with the fabric of Baudelaire’s versification, together with limited musical-semantic interpretation,” means that Vierne’s music remains acutely attentive towards Baudelaire’s poetic vision.

It is tempting to read the selected poems as a progression on themes of loneliness, suffering, despair, and death, but it has also been argued that “coherence is derived less from the textual-thematic content and more from the way in which Vierne establishes subtly demanding relationships between the piano and vocal lines.” Unlike Debussy, Vierne does not disrupt the poetic line but keeps the vocal line largely independent of the piano. As a result, the bond between poem and music is exceedingly weak, as it is possible to recover the poem intact from the song score. “As complex mélodies, the lack of interference with the fabric of Baudelaire’s versification, together with limited musical-semantic interpretation,” means that Vierne’s music remains acutely attentive towards Baudelaire’s poetic vision.

Louis Vierne: 5 Poems de Baudelaire, Op. 45 (Mireille Delunsch, soprano; Christine Icart, harp; François Kerdoncuff, piano)