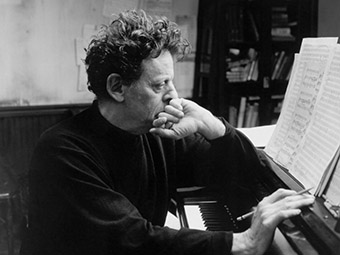

Philip Glass

It starts quietly, a haunting nostalgic hymn-like sequence of gentle chords in both hands. A few bars in, the bass accompaniment changes into a gently undulating pattern of broken fourths, anchored by a low F. In this opening section, Glass sets out the harmonies, beautiful and consonant, which colour the entire piece.

Now the treble chords become fuller, richer, and the quaver bass line is underpinned by throbbing crotchets. The tempo moves up a notch, along with the dynamic. Soon the treble chords gain more momentum, now divided into quavers and crotchets over an insistent bass line. The mood is anthemic, joyful, enhanced by syncopations in the treble chords and greater momentum in the tempo. Then, suddenly, there is a glorious burst of energy as a driving semiquaver figure takes over in the treble. It’s breathless and febrile, jubilant and celebratory, before the music settle back into the place where it came from and the opening chords, that nostalgic hymn, return.

Wichita Vortex Sutra was composed to accompany beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s famous antiwar poem. The piece was the result of a chance meeting in a bookstore in New York and Glass and Ginsberg decided to collaborate. The piece featured on Philip Glass’s 1990 album Hydrogen Jukebox.

Glass: Wichita Vortex Sutra (version with narration) (Ethan Hawke, reader, Bruce Levingston, piano)

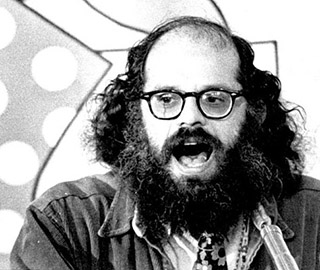

Allen Ginsberg

The poem Wichita Vortex Sutra originated as a voice recording that Ginsberg made with a tape recorder as he travelled to Wichita, Kansas by bus across the American Midwest, back in 1966, at a time when the Vietnam War was growing more intense and deadly, and support for the war in the US was waning. Angry about Vietnam, he spoke directly into the tape recorder as the words came to him, blending his impressions of the passing landscape and news of the day with his own disgust at America’s involvement in Vietnam.

A ‘sutra’ is an aphorism or collection of aphorisms or canonical scriptures in a condensed manual or text found in the literary traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. In Sanskrit the word means “string” or “thread”. Ginsberg’s poem is a spontaneous outpouring, delivered in a series of chanted aphoristic mantras which juxtapose images of the landscape of Kansas and the heartland’s inherent conservatism with horrifying excerpts from media reports of the war. Through the poem, Ginsberg confronts and challenges the meaningless justifications for the American involvement in Vietnam.

© Discogs

Glass composed his score to mirror Ginsberg’s reading of his poem, and the music evokes the stream-of-consciousness style of Ginsberg’s poetry and the meditative, chanting, sometimes effusive, quality of his delivery. The gently nostalgic harmonies, reminiscent of Sacred Harp singing, contrast with the graphic images of war expressed in the poem. Some 50 years since the poem was first composed, it still has the power to move and shock, and retains a strong relevance for our troubled times.

Like Ginsberg’s poem, Glass’s music is an exultant, hymn-like paean to peace, with a forward motion and natural optimism that is hard to resist. For the pianist, it’s a study in control and contrasts, tempering tempo and dynamics to bring the music to its shimmering climax before the softly-spoken final section.