“If only grown-ups were like children, free from prejudice against everything new!”

Anton Webern, 1935

Anton Webern and Wilhelmine Mörtl, the daughter of his mother’s sister, were married in Danzig on 22 February 1911. They had kept their affair ingeniously secret until she found out that she was pregnant with Anton’s child. The marriage caused significant distress to both sets of parents, as the bride and groom were first cousins. In fact, the Roman Catholic Church officially prohibited such a union, and the marriage was solemnized only in 1915. At that time, three of the couple’s four children had already been born. Webern’s first love, however, had been his mother.

Webern’s Passacaglia Op. 1

Amalie Webern (née Geer) introduced him to music, and when she died of diabetes in 1906, Anton was only 22. Devastated he wrote to his friend Alban Berg, “Except for the violin pieces and a few of my orchestra pieces, all of my works from the Passacaglia on relate to the death of my mother.” The obsessive mother-son relationship would haunt Webern for the rest of his life, and Wilhelmine wrote to her future husband, “My love for you will never replace the love of your mother, but it will help you to create a beautiful life. And to assist you in reaching the highest goal as man and artist is the most beautiful part of my own life. I want to preserve your mother’s memory in you.”

Anton Webern: Passacaglia, Op. 1 (Ulster Orchestra; Takuo Yuasa, cond.)

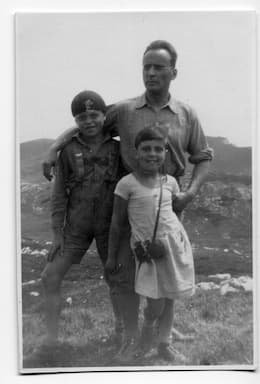

Anton Webern with Minna and Mali

Wilhelmina, or Minna as she was called, gave birth to a daughter on April 1911. Not surprisingly, they christened her Amalie, after Anton’s mother. Nicknamed “Mali,” she was Webern’s favorite and he meticulously recorded her achievements in his diary. He always included family news in his letters to Schoenberg, and in 1930 he writes, “Mali will prepare herself at the university to become a teacher of gymnastics and sports with English as her secondary subject. For four years: gymnastics, skiing, tennis, ice-skating, mountaineering, swimming, etc., in other words, everything that has always represented the ideals of her father.” Webern’s dreams were dashed, however, since Mali was not accepted. Webern, it has been told, took great pleasure of being seen with Mali at concerts, “and he beamed with delight when on one occasion she was mistaken for his wife and addressed as Frau Doktor.” Many of Webern’s composition make references to his favorite places and members of his family. The tone row used in his String Quartet Op. 28 references his parents’ graves at Schwabegg and Annabichl, and abbreviations denote his wife Minna and his four children, Mali, Mitzi, Peter, and Christl.”

Anton Webern: String Quartet, Op. 28 – I. Massig (Schoenberg Quartet)

Webern with Mali, 1915 July

According to his children, family life was rather idyllic. Webern habitually sang them to sleep with a lullaby, and for many years he read to them at bedtime. He even played pranks on them and amused them with various invented children’s games. Every weekend the family went on picnics and family outings in the countryside. However, things were rather structured at home as Webern possessed an extreme sense of orderliness. He pedantically controlled every detail of his domestic life, “from the arrangement of the furniture to the placement of household utensils such as the bread basket or the water jug.” His study, which Webern described as his “inner sanctum,” was located at the end of the corridor to ensure peace and quiet. Except for his wife, only Mali was permitted to enter his study, as she was the only one considered reliable enough to preserve her father’s order. Mali reported, “Pencils lay on his desk aligned according to length and color, and when sharpening them she had to be careful to put them back into the same position.”

Anton Webern: Children’s Piece for Piano (Kinderstuck) (Roland Pöntinen, piano)

Webern with Peter and Christl, 1928

Webern’s second daughter Maria, like her mother, was very quiet and reserved. Although highly intelligent, she did not pursue an academic career but became a kindergarten teacher. Discipline in the Webern household was in the domain of the mother. That discipline could be rather strict and severe, as their son Peter was required to hold a cane across his back on their Sunday walk to correct his slouching posture. Peter would eventually join the Nazi party and die of wounds suffered in a strafing attack on a military train in February 1945. When air raids over Vienna became unbearable, Webern and Minna fled to Mittersill, home to their daughter Christl and her husband Benno Mattel. Webern had not written a single note since the death of his son, and unbeknownst to him, Benno had been engaging in black market activities. A clandestine sting operation had been set up for September 15, and when Webern went outside after dinner to smoke a cigar, an American soldier shot him three times in the stomach. Webern collapsed and died almost instantly; his wife Minna died in 1949.

Anton Webern: 5 Pieces, Op. 10 (Philharmonia Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)