Alfred de Musset

The French dramatist, poet and novelist Alfred de Musset (1810-1857) is probably best known for his autobiographical novel La Confession d’un enfant du siècle (The Confession of a Child of the Century). It was inspired by his scandalous real-time affair with the flamboyant woman who called herself George Sand.

De Musset – Nuits, 1911

Musset’s Confession is a brutally honest and passionate account of a young man’s rite of passage. It tells the story of Octave, desperate to be more than just an average man. He searches for happiness first as a debauched libertine, until his mistress Elise is unfaithful, and then in an austere life in the countryside, where he falls in love with the selfless Brigitte. But as he becomes consumed by insane jealousy and convinced that Brigitte will betray him, Octave brings about his own destruction. This portrayal of obsession and despair stirringly expresses the failed idealism of the Romantic generation of the early nineteenth century. Musset was a well-known figure in brothels and is widely accepted to be the anonymous author-client who beat and humiliated the author and courtesan Céleste de Chabrillan, also known as La Mogador. Predictably, Musset’s earthy poetry, full of delicious ennui and angst quickly attracted a substantial number of musical settings.

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Nuit de mai (Gustavo Porta, tenor; Carlo Aonzo, lute; Paola Esposito, mandola; Orchestra Sinfonica di Savona; Paolo Vaglieri, cond.)

In his Nuit, written between 1835 and 1837, Musset traces the emotional upheaval of his love for George Sand from early despair to final resignation. “La Nuit de Mai” unfolds as a dialogue between the poet and his muse, and Ruggero Leoncavallo was inexorably drawn to the famous opening stanza.

De Musset – Nuits, 1911

Poète, prends ton luth, et me donne un baiser;

La fleur de l’églantier sent ses bourgeons éclore.

Le printemps naît ce soir; les vents vont s’embraser;

Et la bergeronnette, en attendant l’aurore,

Aux premiers buissons verts commence à se poser.

Poète, prends ton luth, et me donne un baiser.

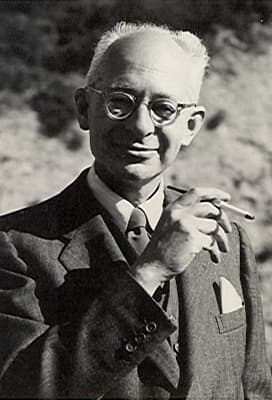

Ruggero Leoncavallo

Leoncavallo used Musset’s long poem as the basis for his “Grand poème symphonique,” in which he musically set fragments from La Nuit de Mai. He was looking for “a kind of dialogue between the poet and orchestra, attempting to express in this way the ideas that the poet develops from the muse.” All twelve movements sound independent musical material but are unified by the cyclical repetition of the opening. The five movements with tenor are based on the literary text, and the seven movements for orchestra reveal a text incipit that appears at the head of each movement.

Rebecca Clarke: Viola Sonata (La Nuit de mai) (Marina Thibeault, viola; Marie-Ève Scarfone, piano)

Rebecca Clarke, 1919

Two lines from Musset’s La Nuit de Mai preface the Viola Sonata by Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979). The work was composed in 1919 for the competition sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge as part of her annual chamber music festival held in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. 73 composers anonymously submitted entries for viola and piano, the chosen instrumentation of that year. Infamously, the six judges were deadlocked between the two finalists, and in the end Ernst Bloch’s Suite for Viola was declared the winner.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

Clarke remembered, “and when I had that one little whiff of success that I’ve had in my life, with the Viola Sonata, the rumor went around, I hear, that I hadn’t written the stuff myself, that somebody had done it for me. And I even got one or two little bits of press clippings saying that it was impossible, that I couldn’t have written it myself.” The celebrated line “Poète, prends ton luth” (Poet, take up your lute) appears as an epigraph on the first page of the sonata, and the delicate modal recitative in the concluding movement is prefaced by “le vin de la jeunesse fermente cette nuit dans les veines de Dieu” (the wine of youth ferments tonight in the veins of God).

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Cielo di settembre, Op. 1 (Alfonso Soldano, piano)

According to Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968), “Cielo di settembre was written long before I had any formal training, but it can be considered my first official work.” Composed in 1910, Castelnuovo was looking to explore the depths of emotional music through a focus on tonal colors and constantly shifting harmonies. Cielo di settembre takes its name from a line of Musset’s poem “A quoi rêvent les jeunes filles.” The score in the original publication, is preceded by the line, “Mais vois donc quel beau ciel de Septembre…”

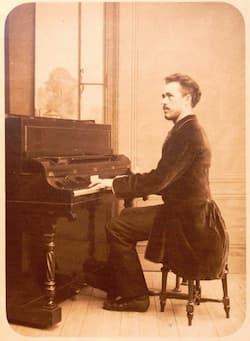

Benjamin Godard, 1880

Benjamin Godard (1849-1895) was child prodigy violinist who entered the Paris Conservatoire at the age of 10. He studied with the great Belgian virtuoso Henry Vieuxtemps, and he published his first violin sonata at the age of 16. He twice competed unsuccessfully for the Prix de Rome, but nevertheless decided to devote himself entirely to composition. Over the next thirty year he wrote prolifically in almost all genres, adhering stylistically to models provided by Schumann and Chopin. His distaste for the rhetorical excesses of Wagner led him to explore a poetic lyricism exemplified in his early Trois Fragments Poétiques, Op.13. Long-spun lyrical melodies are spiced with unusual harmonies and fit perfectly with the differing demands of the salon and concert hall. Published in 1869, each fragment bears the title of a poet, Lamartine, Musset, and Hugo.

Benjamin Godard: Fragments poetiques, Op. 13 – No. 2 Alfred de Musset (Eliane Reyes, piano)

The epigraph appears only once on Clarke’s Sonata, at the very beginning, on the first page of music. The rules of the Coolidge competition required each composer to use a pseudonym or “chiffre” to conceal his or her identity during the judging. Clarke slapped on a scrap of de Musset, which she decided — after the fact, and having nothing to do with the piece’s conception or composition — seemed to approximate its essential energy. When the Sonata was first performed, and again when it came to be published, she kept de Musset’s couplet as an epigraph. The lines were not separated and distributed over the movements. Clarke’s own contemporaneous program-note makes it clear that the Sonata was designed to show off all the capabilities of the instrument — her own instrument, let us not forget — not to express some extrinsic poetic idea. For accurate, up-to-date information on Clarke’s life, career, and works, please see her official website, http://www.rebeccaclarkecomposer.com.