Alfred de Musset’s self portrait with George Sand

When Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) was commissioned to compose a new opera in 1884, his choice of story fell on Edgar, a tragedy inspired by La coupe et les lèvres by Alfred de Musset. The librettist Ferdinando Fontana took some liberties, as Frank became Edgar, Deidamia became Fidelia, and Belcolore became Tigrana. He also moved the action from the Tirol to the Flanders of the 1300s. Puccini worked on the opera for four years, but the premiere in 1889 was hardly successful. For one, critics heavily criticized the libretto, and attacked the young composer on the basis of too much borrowing from Bizet.

Giacomo Puccini

At any rate, the opera was dropped after only three performances. The plot revolves around an intense love triangle, with Edgar torn between his love for the innocent and pure Fidelia, and his passion for the sultry Tigrana, her adopted sister. Fidelia’s brother, Frank, loves Tigrana, but she scorns him. As the villagers leave the church after Sunday Mass, Tigrana taunts them with a provocative song, infuriating them. When they threaten her, Edgar leaps to her defense and becomes enraged, burning down his house and announcing his departure with Tigrana in a fit of passion. Frank appears and challenges Edgar to a duel, despite appeals for calm from Fidelia and her father. Frank is wounded, and Edgar and Tigrana escape as the villagers curse them.

Giacomo Puccini: Edgar (Renata Scotto, soprano; Carlo Bergonzi, tenor; Gwendolyn Killebrew, mezzo-soprano; Vicente Sardinero, baritone; Mark Munkittrick, bass; New York Schola Cantorum; New York Opera Orchestra; Eve Queler, cond.)

Lili Boulanger

In Act II of the opera, Edgar is filled with remorse for having left Fidelia, and he is growing tired of Tigrana. When a group of soldiers passes by, the impulsive Edgar joins them, recognizing Frank as their leader. The two make peace, and Edgar prepares to leave as Tigrana swears revenge on her faithless lover. In Act III, Frank and a monk chant a funeral requiem for Edgar, supposedly lost in battle. As Frank recounts the soldier’s heroic death, the monk reminds the crowd of Edgar’s wrongdoings. Incensed, the crowd tears open the coffin intending to throw Edgar’s body to the ravens, but all that remains is an empty suit of armor. The monk pulls off the hood hiding his face: he is none other than Edgar! As Fidelia throws herself into his arms, Tigrana suddenly reappears and stabs her to death. As Fidelia’s lifeless body drops to the ground, Edgar falls upon her in grief and the murderess is led away by the soldiers to her execution. The original funeral scene from Act IV of Musset’ play served Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) as the inspiration for her “Pour les funérailles d’un soldat” for baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra of 1912.

Qu’on voile les tambours, que le prêtre s’avance.

A genoux, compagnons, tête nue et silence.

Qu’on dise devant nous la prière des morts.

Nous voulons au tombeau porter le capitaine.

Il est mort en soldat, sur la terre chrétienne.

L’âme appartient à Dieu; l’armée aura le corps.

Si ces rideaux de pourpre et ces ardents nuages,

Que chasse dans l’éther le souffle des orages,

Sont des guerriers couchés dans leurs armures d’or,

Penche-toi, noble cœur, sur ces vertes collines,

Et vois tes compagnons briser leurs javelines

Sur cette froide terre, où ton corps est resté!

Lili Boulanger: Pour les funérailles d’un soldat (Vincent Le Texier, baritone; Namur Symphonic Choir; Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra; Mark Stringer, cond.)

Bizet’s Djamileh

It might come as surprise, but both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler considered Djamileh, the one-act opera by George Bizet, a work worthy of being included in the repertory of Opera comique greats. In fact, Mahler conducted the Vienna premiere in 1898 and all 18 repeat performances until 1902. Djamileh is actually based on the poem “Namouna” by Alfred de Musset. Haroun, a spoiled young man from a noble house changes his mistress at each new moon, which his servant Splendiano buys for him at the Cairo slave market. However, the beautiful Djamileh unfortunately falls in love with Haroun, and she asks Splendiano—who is also interested in her affections—for help. She wants him to smuggle her among the new “recruits” so that she can appear before Haroun one more time and try to win his heart. If she should fail, she promises to give herself to Splendiano. Disgui¬sed, she dances before Haroun, who buys the graceful stranger and eventually falls in love with his mistress. Throughout the opera, only Djamileh suffers and experiences profound feelings, and her character eventually inspired the much better-known Carmen.

George Bizet: Djamileh, Act I: Nour Eddim roi de Lahore (Denyce Graces, mezzo-soprano; Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra; Marc Soustrot, cond.)

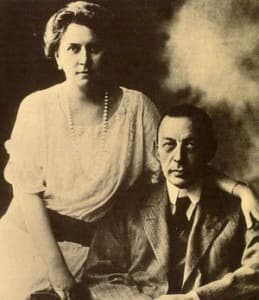

On 12 May 1902, Sergei Rachmaninoff married his cousin Natalia Satina after a three-year engagement. Because they were first cousins, the marriage was essentially forbidding by the Russian Orthodox Church. However, Rachmaninoff had just sold his 12 Songs, Op. 21 to his publisher for 3,000 rubles, which expedited the marriage process considerably. For one of his settings, Rachmaninoff relied on a fragment by Alfred de Musset in Russian translation. According to legend, de Musset had just been inspired when a friend took him out to dinner. Sadly, inspiration never returned, and the poem remained a fragment.

Sergei Rachmaninoff and Natalia Satina

Pourquoi mon cœur bat-il si vite?

Qu’ai-je donc en moi qui s’agite

Dont je me sens épouvanté?

Ne frappe-t-on pas à ma porte?

Pourquoi ma lampe à demi morte

M’éblouit-elle de clarté?

Dieu puissant! tout mon corps frissonne.

Qui vient? qui m’appelle? — Personne.

Je suis seul, c’est l’heure qui sonne;

Ô solitude! ô pauvreté!

Rachmaninoff finely controls the balance between voice and accompaniment, as the piano offers insight into the text. The accompaniment underlines the unsettling atmosphere of the poetry, and grand melancholy chords provide a fitting conclusion.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter