The set of ballet Parade, designed by Pablo Picasso

The premiere of the ballet Parade at the Théâtre du Châtelet in May 1917 turned into a veritable riot. Jean Cocteau, the author of the story claimed, “I have heard the cries of a bayonet charge in Flanders, but it was nothing compared to what happened that night at the Châtelet. As the ballet ended, the mounting anger of the audience boiled up into an uproar. Cocteau reported that cries of “Sales Boches” (Dirty Germans) were shouted at the company and that some viewers demanded that the people involved in Parade be sent to the front. A fistfight broke out, and Cocteau reported, “an irate female accosted me and tried to put my eyes out with a hatpin,” and of a man who said to his wife, “If I’d known this was going to be so silly, I’d have brought the children.”

Erik Satie: Parade – Choral – Prelude du Rideau rouge – Prestidigitateur Chinois (Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy; Jerome Kaltenbach, cond.)

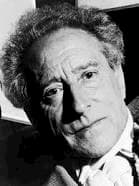

Jean Cocteau

Parade was Jean Cocteau’s brainchild, and he knew from the beginning that this multimedia spectacle and ballet would almost certainly antagonize and offend the audience. To realize his vision Cocteau assembled a unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time. Serge Diaghilev and the “Ballets Russes” commissioned and performed the piece, Léonide Massine provided the choreography, Pablo Picasso designed and painted the costumes and the set—including the red opening curtain, Guillaume Apollinaire wrote the program notes for the first performance and invoked the word “surrealism” for the first time, and the “enfant terrible” of the Parisian café-concert scene Erik Satie composed the music. In the audience that fateful evening was Jean Marie Octave Géraud Poueigh, a composer, musicologist, music critic, and folklorist. At the end of the performance Poueigh came backstage, shook Satie’s hand and congratulated him on the performance.

Erik Satie: Parade – Petite fille Americaine (Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy; Jerome Kaltenbach, cond.)

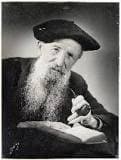

Erik Satie

Things got slightly interesting when Poueigh, who wrote music criticism under the pseudonym Octave Séré, published a review in the newspaper Les Carnets de la Semaine. He lambasted the ballet as being unpatriotic at a time when many soldiers were dying on the battlefields of WWI, and called it “an outrage on French taste.” And for good measure, he slated Satie “for his lack of wit, skill and inventiveness.” Satie was outraged and immediately sent Poueigh a series of insulting hand-written postcards. Satie certainly did not spare the verbiage, as we may easily gauge from the choice sample below.

Fontainebleau, 5 June 1917

Satie to Monsieur Fuckface Poueigh

Famous Gourd and Composer for Nitwits

Lousy ass-hole, this is from where I shit on you with all my force.

Never again offer me your dirty hand.

The postcards were surely written to provoke a response, and indeed they did. Poueigh accused Satie of slander, noting that the insults had been written on the back of postcards, visible to all including the mail man and his kind concierge. And thus, the Satie/Poueigh affair went to trial.

Erik Satie: Parade – Acrobates – Final – Suite au Prelude du Rideau rouge (Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy; Jerome Kaltenbach, cond.)

Jean Poueigh

On July 12 Satie appeared in court, and Poueigh’s attorney pressed the court for a one-year sentence for public defamation. Incensed, Cocteau raised his cane at Poueigh’s lawyer, and was subsequently arrested and beaten by police for repeatedly yelling “arse” in the courtroom. Cocteau was eventually fined, and Satie sentenced to a week in prison without parole. He was also ordered to pay a fine of a hundred francs plus one thousand francs in damages to Poueigh. Satie immediately launched an appeal, but the final verdict read in November came out in Poueigh’s favor. Princesse de Polignac came to Satie’s aid, and she loaned Satie the money to cover the fine and damages. Misia Edwards, Diaghilev’s patron meanwhile, lobbied the courts and on 15 March 1918 the affair came to a close. Satie’s sentence was suspended “on the condition that he show good conduct and not receive any prison sentence for five years.” Satie did manage the good behavior, but he did not pay the damages to Poueigh. As he wrote to the Princesse in October 1918, “I have no intention of giving one cent to the noble critic who is the cause of my judiciary ills, and instead ask for permission to use the money for living expenses.” Apparently, Satie’s wish was granted.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter