Johann Christian Bach

Johann Christian Bach was one of the leading composers of his day; if you don’t believe me, just ask Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart! But the “London Bach” was also known in legal circles, as he brought the first legal action for breach of musical copyright. Bach’s actions helped to clarify the legal status of music, and greatly aided the development of copyright law. Bach arrived in London in 1762 and by December 1763 was granted a royal privilege giving him exclusive rights to publish his music for 14 years. For a couple of years, Bach acted as his own publisher, issuing his music in London under his own imprint. After 1765 Bach gave up the publishing business in order to concentrate on an annual concert series jointly operated with his composer friend Carl Friedrich Abel. However, Bach kept a seriously keen eye on the publishing trade.

Johann Christian Bach: Keyboard Concerto in D Major, Op. 1, No. 6 (Anna Galperin, piano; Prague Pro Musica; Adolphe Schwartz, cond.)

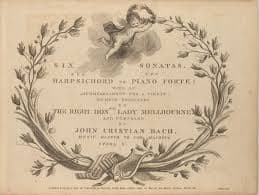

J.C. Bach’s Keyboard Sonatas

On 18 March 1773, Bach filed a complaint in Chancery against the music sellers James Longman and Charles Lukey, accusing them of printing and selling two of his works composed in 1769 without his permission. The works in question were two keyboard sonatas; one in G major for solo keyboard that was sold by Longman and Lukey as “A New Lesson for the Harpsichord or Piano Forte,” and the other a sonata in F major for keyboard and viola da gamba, now lost. Although he cited his royal privilege as one reason for the suite, Bach also argued that he deserved protection under the “Statute of Anne.” That particular judgment, also known as the “act for the encouragement of learning” of 1710 stipulated that authors of book had exclusive publication rights for 14 years from the date of publication. This period was automatically extended to 28 if the author was alive at the end of the first 14-year period. So far so good, but the preamble to that act referred vaguely to “books and other writings,” with music—not considered writing in the most literal sense of those terms—falling outside the scope of the act.

Johann Christian Bach: Keyboard Sonata in G Major, Op. 5, No. 3 (Sophie Yates, harpsichord)

The Longman and Lukey Publication

And thus the legal wrangling commenced. The publishers initially claimed that they were not aware that Bach had been granted a royal privilege, and questioned whether Bach was actually the true author of the work. They also claimed that they had purchased the copies from a local music seller, Adolphus Hummell, “to whom Bach had given the works, and therefore should be allowed to continue to print and sell the music, and not have to hand over the “very trifling” profits, to Bach.” Bach was forced to change direction slightly, and appended his own petition to a larger petition by booksellers that argued that written copyright should apply in perpetuity. That petition was unsuccessful, and a further 1775 ruling stated “the Crown had no power to grant privileges that created a printing monopoly for individuals, which effectively rendered Bach’s royal privilege useless as a means of legal argument.”

Johann Christian Bach: Symphony in E-Flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2 (Miklós Spányi, clavichord; Concerto Armonico Budapest; Peter Szuts, cond.)

Bach was thus forced to press in the courts his argument that the “Statute of Anne” governed music. The case finally came before the Lord Chancellor in May 1776. The court referred the question to the King’s Bench. On 16 June 1777 the full King’s Bench certified to the Court of Chancery that the Copyright Act protected music. When the Court of Chancery heard the case again on 8 July 1777, it ruled that “Longman and Lukey must pay Bach all profits from the sale of the two sonatas, and acknowledge that the works were the exclusive property of Bach.” It had been established that musical notation fell into the category of “other writings,” and the ruling “treated notation as a form of written language, “visible and known characters” that could be produced and reproduced in a tangible form—a form that could be identified, distinguished, and appropriated. As such, it exhibited the required characteristics to qualify as a form of property.” Bach had won, and in due course, it clearly established that composers were authors, and that their works are a valuable and protectable commodity. Case closed, but isn’t it utterly amazing that 250 year later this fundamental concept is still not fully respected or understood in some parts of the world?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter