Manuscripts from different composers © Classic FM

The saying goes this way, quality over quantity. But what if the saying was: quantity creates quality? What if instead of focusing on one or the other, one would lead to the other? In order to grow, a composer — or any artist for the same matter — develops creative habits, and these habits result in a vast creative output. While some musicians — the perfectionists — would rather keep the work in progress unrevealed, some take the opportunity to create works that are statements of their creative evolution.

Telemann, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven, Mozart etc. have all been characterised as prolific composers, and have a catalog that ranges from 3,000 works for Telemann to 600 for Mozart. In his book The Top 10 of Everything, Russel Ash ranks composers with the total hours of music they composed; Haydn sits at the top with 340 hours, followed by Handel with 303 and Mozart with 202. On a yearly basis — and taking in consideration the length of the life of each composer — that is a considerable amount of music. What all these numbers tell us about these musicians, is that the quality of their work — and why they are today considered as “the best” — is directly related to the quantity of their work. Out of all these numbers, it would not be necessarily true to affirm that these works are all equal: that Mozart’s first childhood work and his last — the Requiem in D Minor — sit at the same level for instance.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Requiem in D Minor, K. 626 (Barbara Bonney, soprano; Monteverdi Choir; English Baroque Soloists; Anne Sofie von Otter, contralto; Susan Addison, trombone; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; Willard White, bass; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

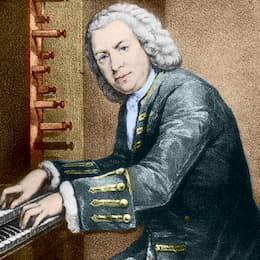

Bach, as kapellmeister, would publish and perform music to a deadline on a daily basis. © The Purity Spiral

Traditionally, when creating music was equal to the work of a craftsman and performed within a religious environment, a composer would create music on a daily basis; for mass services, celebrations and events. It is not until the 19th century that musicians started composing music independently. Bach, as kapellmeister, would publish and perform music to a deadline on a daily basis, which implies that he would find a balance between quality or perfection and completion. Actually, he would often recycle and reuse some of his ideas in different works; allowing him to develop them differently, and in some cases improve them. The sinfonia from his cantata 29 “‘Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir” and the “Prelude” of the Partita No. 3 in E Major for Violin are essentially the same works.

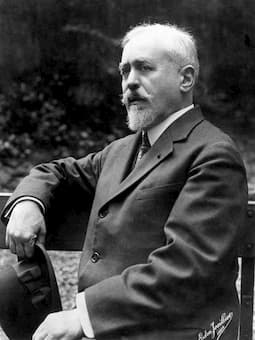

Some perfectionists, such as Paul Dukas, would not publish a work until they deem it perfect. © GrandRapidsMN.com

Some composers chose not to reveal the works that they consider as minor or of a lesser quality. Some — like Beethoven — are even famous for destroying the works that they considered as not being good enough. Bellini, Mahler or Berg are all composers who have appeared as being less prolific due to a smaller amount of their work being published; however this does not affect the size of their work. Some perfectionists, such as Dukas, would not publish a work until they deem it have reached its full potential and perfect state.

On a personal note, it seems that the most important is not realistically the result but the journey towards it. How creating a piece of music and reaching its completion ignites a new possibility and a new piece of work to be created afterwards: how one progress leads to another. Each piece that exists is an opportunity to learn and grow as an artist, and not necessarily an end in itself.

What is interesting with Bach, is how he introduced an idea in a piece for keyboard and later redeveloped it in an orchestral piece. How the evolution of the craftsman can be observed throughout his work and his life, and how this life — and the times that accompany it — reflects in his works.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter