Portrait of Beethoven by Johann Stephan Decker, 1824

In April 1825 Ludwig van Beethoven developed a serious intestinal illness. His exact condition was unclear, but his doctor ordered him away from Vienna to rest at the nearby spa of Baden. Placed on a strict diet and forbidden to drink wine, Beethoven clearly feared for his life. As he wrote to the writer and critic Ludwig Rellstab, “Forgive me in consideration of my very delicate health. As perhaps I may not see you again, I wish you every possible prosperity. Think of me when writing your poems.” In the end, Beethoven did get better and during recovery he composed the “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart” roughly translated as “Song of Thanksgiving to the Deity from a convalescent in the Lydian mode.” Essentially, it is an autobiographical musical offering of a prayer of thanks after his illness that became part of his String Quartet Op. 15. Its narrative unfolds in five sections, opening with a bleak section in Lydian mode that has been described to “the feeling you get trapped in hospital for days without end.” Beethoven labels the second section “Neue Kraft fühlende,” or “Feeling New Strength,” as the austerity of the first section collapses into an optimistic universe of harmonies and trills. The process of alternating these themes continues until Beethoven turns the “whole soundscape into a floating world of transcendental emotion.” We are left to wonder if Beethoven attempted to separate the music of his turbulent personal life from an idealized one. As Edward Dusinberre recently remarked, “In the midst of these current awful circumstances—people are dealing with such uncertainty and illness and death—to play (and to hear) a piece like this can give us hope. That is where the power of the music is.”

Beethoven’s Song of Thanksgiving to the Deity from a convalescent in the Lydian mode

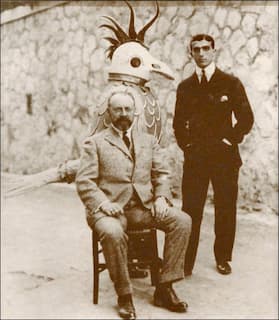

Henri Matisse and Léonide Massine preparing the ballet Le chant du rossignol (debut February 2, 1920) with the mechanical Nightingale.

Five days after the première of the Rite of Spring, Igor Stravinsky was admitted to hospital with acute enteritis, which soon emerged as full-blown typhoid fever. The victim of having eaten a bad oyster, he stayed in the Villa Borghese nursing home for more than five weeks. During that particular period, his wife gave birth to their fourth child and contracted tuberculosis. During the period of his recovery, and the recovery of his wife in the Swiss Alps, Stravinsky finished a commission from the newly formed Moscow Free Theatre.

Le chant du rossignol, 1920

Stravinsky had written the first act of Le rossignol, based on Hans Christian Andersen’s 1843 tale “The Nightingale” in 1908. The plot is deceptively simple. The Nightingale sings for the Emperor of China, who is terribly pleased. When the Emperor of Japan provides the gift of a mechanical nightingale, all are mesmerized by its song and ignore the real Nightingale, who flies away. In the final scene, the Emperor meets Death, due to illness and suffering from having lost the real nightingale. The Nightingale appears outside the Emperor’s window and convinces Death to let the Emperor go. Once he has recovered, the Nightingale flies away and returns to nature. The opera was not well received, but eventually Stravinsky prepared a symphonic poem Le chant du rossignol for the ballet stage in 1917.

Igor Stravinsky: Chant du rossignol (Song of the Nightingale) (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin by Delacroix

When Frédéric Chopin met up with George Sand again in 1838, both had been through difficult periods in their lives. Sand later remarked, that it had been above all a strong maternal instinct, which had drawn her to Chopin. Be that as it may, by early June the pair became lovers, and they subsequently decided to spend the winter months of 1838/39 in Majorca. They rented rooms in an old Carthusian monastery at Valldemosa, just a couple of hours away from Palma. That location was ill chosen, as unable to deal with the harsh Majorcan winter, Chopin’s health deteriorated rapidly. By late January his illness had reached a shocking state, and they were obliged to leave the island for Marseilles.

Portrait of George Sand by Delacroix

Under the care of Dr. Cauvières, Chopin underwent a long period of convalescence but was finally able to report “they no longer consider me consumptive.” By 1 June he first laid eyes on Nohant, Sand’s home in Berry and much of his greatest music was composed there. It started after his recovery during the summer of 1839. He swiftly composed the Mazurkas op.41, the second of the two Nocturnes op.37, the F-sharp major Impromptu op.36 and the remaining three movements of the B-flat minor Sonata op.35.

Frédéric Chopin: Nocturnes Op. 37, No. 2 (Garrick Ohlsson, piano)

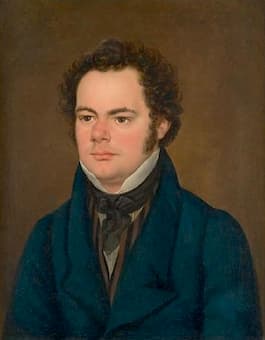

Franz Schubert, c. 1827

In the autumn of 1822, Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) contracted syphilis. Within a few weeks he began to exhibit symptoms, which included symmetrical rashes on the palms of his hands, headaches, dizziness and loss of voice. Admitted to the Vienna General Hospital for six months, he received the textbook treatment prevalent at the time, namely “The treatment of syphilis by the inunction of mercury.” Schubert had to stick with a strict diet, avoiding meat and starchy food, with no milk, coffee or wine allowed. Repeated baths prepared Schubert to the inunction, carried out in a small room, dry and free of drafts.

Elecampane and mercury ointment jar

During treatment, the patient could not leave the room, and could not change underwear and bed sheets. The inunction was administered in the evening, and consisted of a mixture of lard and mercury. The first inunction was applied to the legs from the ankle to the knee, the second to the thighs. The 3rd and 4th to the left and right arm respectively. The back is used for the 5th inunction, and the 6th may be on the belly with the cycle repeated the next day. The side effects were hellish, and included a burning mouth, metallic taste, difficulty swallowing, diarrhea and diuresis, and high fever. Enduring this kind of torture for six months, Schubert must have sensed that his life was going to be cut short. Yet in periods of remission, he composed some of his greatest works. Schubert writes, “The product of my genius and my misery, and that which I have written in my greatest distress, is that which the world seems to like best.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter