David: The Coronation of Napoleon (1807)

In the 19th century, the rise of Napoleon and the threat he posed to all of Europe (and Russia) cannot be underestimated. As his victorious armies swept from border to border, whole nations fell under his sway.

Those with revolutionary or anti-establishment sentiments had to keep them under wraps, or disguise them as historical reports, or somehow sublimate personal beliefs with public innocence.

We know that Napoleon’s actions affected Beethoven, witness his rededication of his Symphony No. 3 from “Buonaparte” to “to a heroic man.”

Ferri: Coriolanus at the Gates of Tome

In 1807, Beethoven wrote an overture for the 1804 play Coriolan by Heinrich Joseph von Collins. In the tragedy, Coriolan, a Roman General of the 5th century BC, had fled in exile to his enemies, the Volsci. He persuaded the Volsci to break their truce with Rome and led their army to Rome, recapturing their lost cities along the way. At Rome, as he was at the gates, his mother, wife and his two sons came to plead with him to stop the invasion. He ceded to their demands, withdrew from the gates of Rome, and vanishes from history.

He doesn’t vanish from the drama however. Coriolan has now been traitor to two powers: to Rome for going to their enemies, and to the Volsci for having given up with on the brink of victory. In Shakespeare’s Coriolanus he’s assassinated. In Collins’ Coriolan he kills himself at the gates of Rome.

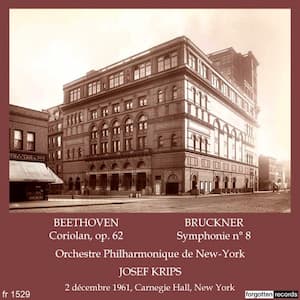

Josef Krips

From the very beginning, Beethoven introduces us to a hero who is filled with anxiety – this isn’t an overture of a decisive hero, as we met in his Egmont Overture, but rather a man who is pitched at the highest level. The second theme represents his mother’s pleadings with him – which is then overlaid by his nervous theme again. It’s a very skillful representation of the opposing feelings with which Coriolan must contend.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Coriolan Overture, Op. 62

This 1961 radio broadcast from Carnegie Hall of the New York Philharmonic was led by conductor Josef Krips. Krips (1902-1974) was an Austrian conductor and violinist. His conducting career started in 1921 when he was Felix Weingartner’s assistant at the Vienna Volksoper. After the war, Krips was principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra before going on to lead the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra (to 1953), and the San Francisco Symphony (to 1970). He was widely recorded.

Performed by

Josef Krips

Orchestre Philharmonique de New York

Recorded in 1962

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter