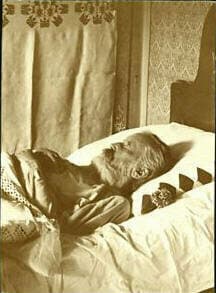

Brahms on his deathbed, 1897

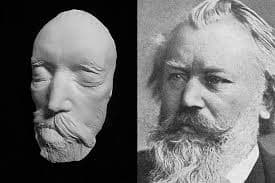

At the end of the summer of 1896, Johannes Brahms was displaying some typical jaundice symptoms. The whites of his eyes and the mucous membranes had started to turn yellow. His doctors continued to observe Brahms for several months before they diagnosed him as having cancer of the liver at the beginning of 1897. Brahms was last publically seen at a performance of his 4th Symphony on 7 March 1897, and shortly thereafter he quietly attended the premier of the Strauss operetta “The Goddess of Reason.” His condition worsened gradually, and Brahms died on 3 April 1897 at the age of 63 in Vienna. Eugen von Miller took a photograph, Ludwig Michalek drew a pencil sketch, and Karl Kundmann molded the death mask. Brahms was sealed into his casket on April 4, and the funeral procession announced for 6 April 1897. Vienna’s time-honored ritual of “a beautiful corpse,” is essentially a majestic send-off to reap eternal reward, as promised by the Catholic faith. And in the case of Brahms, we do have knowledge of the music performed at Brahms’ Funeral.

Johannes Brahms: 6 Lieder und Romanzen Op. 93a, Nr. 4 “Fahr wohl” (Wolf-Dieter Hauschild, cond.; Leipzig Radio Chorus)

Death mask of Johannes Brahms

The funeral procession was organized by the Society of the Friends of Music. Brahms had served this association in various capacities for decades, and the Brahms casket was picked up from his residence adjacent to the church of St. Charles. Dignitaries from all walks of life and from all over Europe had gathered, including the composers Antonin Dvořák and Ferruccio Busoni, the pianist Emil Sauer and members of the “Female String Quartet of Vienna,” amongst numerous others. The procession stopped in front of the famous building of the Society—the New Year’s Concert of the Vienna Philharmonic is performed there every year—and a choir sang “Farewell,” from Brahms’ Songs and Romanzes Op. 93a. The procession then passed by the opera house and continued to the protestant church in the Dorotheergasse. The church choir sang the Bach chorale setting of “Jesus my sure Defense,” and Max Kalbeck reports, “Since everybody attending was Catholic, nobody knew the text or the music.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Chorale “Jesus meine Zuversicht” BWV 365 (Chamber Choir of Europe; Martina Rotbauer, viola da gamba; Robert Sagasser, viola da gamba; Ute Petersilge, baroque cello; Heike Hummer, violone; Jorg Halobek, organ; Jens Wollenschlager, organ; Nicol Matt, cond.)

The church was clearly unable to accommodate the huge number of mourners, but the service got properly underway with the church choir singing an arrangement of Mendelssohn’s “It is certain in God’s wisdom,” from his 6 Songs Op. 47.

Felix Mendelssohn: 6 Gesänge, Op. 47, No. 4 “Es ist bestimmt in Gottes Rath”

Funeral Procession for Johannes Brahms

In his Eulogy, the pastor honored “a high priest in the truly beautiful art, and a powerful ruler in the kingdom of tones. A soul full of wonderful melodies has breathed its last sigh, and a noble man has completed his earthly troubles. Master Johannes Brahms did not die as his spirit has overcome death and ascended into the bright, blissful world of pure harmony and peace.” Schubert’s “Wanderers Nachtlied I,” setting the famed poem by Goethe, musically reinforced the message of the eulogy.

Franz Schubert: Wanderers Nachtlied 1, Op. 4, No. 3, D. 224 “Der Du von dem Himmel bist” (You who come from heaven) (Ulf Bästlein, baritone; Stefan Laux, piano)

Grave of Johannes Brahms,

Central Cemetery, Vienna

Brahms had no special wishes regarding the music to be performed at his funeral, but apparently he had quietly mentioned to a friend that he wanted to be buried close to Beethoven and Schubert at the Vienna Central Cemetery. His casket arrived there in the evening of April 6, accompanied by close friends and colleagues. In both the eulogy and the short address at the open gravesite, the speakers made reference to the 4 Serious Song, which Brahms, already sensing the end, had completed shortly before his death. For many listeners then and now, these songs represent “sounds from a higher realm, where love and peace reign forever.” Given the current struggles with Corona around the world, that’s certainly a message to keep in mind.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Vier Ernsten Gesänge, Op. 121 (Matthias Goerne, baritone; Christoph Eschenbach, piano)

A wonderful essay.

Very interesting. Thank you

I wonder if any of the Schumann children attended?

Alas! A simple cupping therapy and bloodletting would have cured him. Especially bloodletting from the back of his ears. But all in all man dies sooner or later. Alas!