King George V

The United Kingdom is currently in a period of national mourning for Prince Philip, husband to Queen Elizabeth II, who died at the age of 99. The Prince requested a funeral of minimal fuss, and with Corona restrictions in place, he got his wish. His funeral was a much smaller affair indeed, but it was still a regal and dignified event. Substantially contributing to this dignified setting was the music, personally selected by the Duke of Edinburgh for the occasion of his own funeral. Prince Philip had a rather refined taste in music, and prior to the funeral service we heard compositions by J.S. Bach, Sir William Harris, Percy Whitlock, Louis Vierne and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Given the ongoing pandemic, the choir consisted of just four singers, but they nevertheless sang two works commissioned—or as we say within royal decorum, composed on request—by Prince Philip. For his 75th birthday in 1996, Philip requested a setting of Psalm 104 from the guitarist and composer William Lovelady. In addition, when Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip attended the premiere of Britten’s opera “Gloriana,” written to honour the Queen’s coronation, Philip asked the composer for settings of the “Jubliate” and the “Te Deum” for St. George’s Chapel at Winsor. It was only fitting that this request should sound in honour of Philip, and in the location for which it was intended.

Benjamin Britten: Jubilate Deo

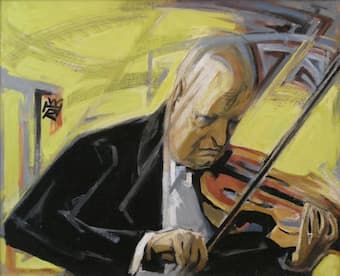

Paul Hindemith with viola

For monarchies around the world, music has always played an important role in paying last respects, and composers have written a variety of dedicated composition. Paul Hindemith traveled to England on 19 January 1936 to perform his viola concerto “Der Schwanendreher.” However, just before midnight on 20 January, King George V died and the concert was canceled. With Hindemith on site, it was decided that he should compose a work honouring his Majesty. In a mere six hours, Hindemith composed his “Trauermusik,” (Mourning Music), for viola and ensemble. The composition was performed on the following day in memory of the King.

Paul Hindemith: Trauermusik (Brett Dean, viola; Queensland Symphony Orchestra; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen

Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen was sickly from birth, and by the time he reached his 21st birthday, he was chronically ill. Hardly surprising that Leopold was preoccupied with death, and for the final two years of his life he meticulously planned his own funeral. Since music had been a huge part of his life, music was also a major part of his funeral. Prince Leopold charged Johann Sebastian Bach—his former employee at the Cöthen Court—with the task of composing and supervising the music for the funeral ceremonies. Prince Leopold died just shy of his 34th birthday on 19 November 1728, but the funeral ceremony was set for the following spring to allow for the “fullest attendance from around the principality.” Leopold had wanted his funeral to be a most lavish affair, so Bach provided a cantata in 24 movements, divided into four parts. “The first deals with the principality in mourning, the second the prince’s departing and the salvation of his soul. The third part, followed by a homily, details Leopold’s commemoration. The final section is about the farewell and about eternal rest.” Sadly, Bach’s music has been lost, but the libretto has survived. Not to worry, however, as we do know that Bach used musical materials which also appears in two surviving works, including the St. Matthew Passion. As such, it was possible to produce a number of possible reconstructions.

Johann Sebastian Bach: “Klagt, Kinder, klagt es aller Welt,” BWV 244a (Sabine Devieilhe, soprano; Damien Guillon, alto; Thomas Hobbs, tenor; Christian Immler, bass; Pygmalion Orchestra; Raphaël Pichon, cond.)

Caroline of Ansbach, queen of the United Kingdom

Queen Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, consort of George II, had been a friend and patron to George Frideric Handel for more than thirty years when she died in 1737. She was considered a woman of great beauty who took a lively interest in artistic and intellectual matters. Caroline was also an accomplished amateur musician, who supposedly exercised “great influence over her husband,” as we can read in a satirical verse:

You may strut, dapper George, but ’twill all be in vain,

We all know ’tis Queen Caroline, not you, that reign –

You govern no more than Don Philip of Spain.

Then if you would have us fall down and adore you,

Lock up your fat spouse, as your dad did before you.

Without doubt, Caroline was a strong woman who had steadfastly refused to convert, and she was widely mourned. Unsurprisingly, Handel received the commission to compose an anthem within a week to a chosen text. “The Ways of Zion do Mourn” was heard at Caroline’s funeral in Westminster Abbey on 17 December 1737, and described as “an exceedingly fine composition adapted very properly to the melancholy occasion.” Not wanting to waste great music, Handel subsequently re-worked the anthem 2 years later and used it for the opening section of his oratorio Israel in Egypt.

George Frideric Handel: “Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline”

Initiation ceremony in Viennese Masonic Lodge, during reign of Joseph II

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Masonic Funeral Music,” hardly unexpected, contains a bit of a mystery. This short masterpiece is dated July 1785, and supposedly composed for the funeral of Mozart’s lodge-brothers Duke Georg August Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Count Franz Esterházy von Galantha. Indeed, it was performed at their funerals on 17th November 1785, but at the time it was written, the royal Freemasons were still very much alive. Mozart became a Freemason on 14 December 1784, during a time when Freemasonry enjoyed a brief period of resurgence. Mozart had already been aware of masonic practices, as his father had cultivated contacts in Salzburg. At the age of 16, Wolferl composed a cantata on commission from a Munich lodge, and during his stay in Mannheim in 1777, Otto Freiherr von Gemmingen sponsored him. Gemmingen was later to become his first lodge Master in Vienna. However, Freemasonry was once again under attack, and by 1800 it was virtually banned. Mozart was not pleased and he even intended to found a secret society called “Die Grotte” (The Grotto). As to the mystery of the “Masonic Funeral Music,” scholars today believe that it was originally composed “as ritual music for the installation of a Master, and subsequently reused at the funeral.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Masonic Funeral Music,” K. 477