© musiciansnet.co.uk

Why does one choose a piece of music over another? The best cello pieces ever written are, for me, the ones that I return to over and over that always seem to offer new insights and emotions. The greatest repertoire will grow with you, will reflect different moods depending on the time of life a musician returns to them, and the audience’s conception will vary too, depending on what they might have experienced in the meantime. Certainly, a great work will reflect the political and collective atmosphere during which it was written. For that reason, I’ve chosen 10 of the best cello pieces by era—moving slowly through history, ending my list with a living composer’s work.

J.S. Bach (1685-1750) — I think most cellists would agree no list can be complete without referring to the masterful and iconic Bach Solo Cello Suites BWV 1007-1012. Virtually every student and professional has played at least a few of the six unaccompanied suites and there are innumerable recordings of these amazing works. For Bach, writing for one solo instrument was unexplored terrain, during a time when the cello was considered a bass instrument that provided rhythm and accompanied the harmony. Each suite consists of a Prelude followed by several dance movements. You may have heard this great music in film, dance, and theater productions. I’ve chosen a wonderful recording by French cellist Opéhlie Gaillard who performs these works on a Baroque cello.

J.S. Bach: Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major, BWV 1012 – I. Prelude (Ophélie Gaillard, cello)

Wendy Warner © Wendy Warner

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) — For me the Haydn Cello Concerto in the sunny key of D major is quintessentially classical. The music is transparent, lighthearted, and full of lovely tunes. At the time, Haydn was employed by the Hungarian Prince Esterházy to write compositions for the Esterházy Court Orchestra. Haydn treated the cello as a virtuosic instrument capable of all kinds of magical melodic spirals. The cellist must play with brilliance and ease—not always easy in this challenging work that wanders through the lowest and highest registers of the instrument. The fast-slow-fast movement structure gives the cellist every opportunity to show off glorious tone, technique, and finesse. Here’s a performance full of delicate grace and virtuosity by cellist Wendy Warner.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major, Hob.VIIb:2 – I. Allegro moderato (Wendy Warner, cello; Camerata Chicago; Drostan Hall, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) — Beethoven wrote five glorious sonatas for cello and piano but of his music for cello, I’ve chosen as one of the greatest cello pieces ever written, his Variations in E-Flat Major on the theme Bei Mannern weiche Liebe fuhlen, from Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute. It’s a short work but in these ten minutes Beethoven covers the entire gamut of human emotion and the cello’s abilities—from elegance to vigor, and from tenderness to pathos. It’s one of my favorites to perform. Gautier Capuçon captures every mood of the piece.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Variations in E-Flat Major on Bei Mannern, welche Liebe fuhlen from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, WoO 46 (Gautier Capuçon, cello; Frank Braley, piano)

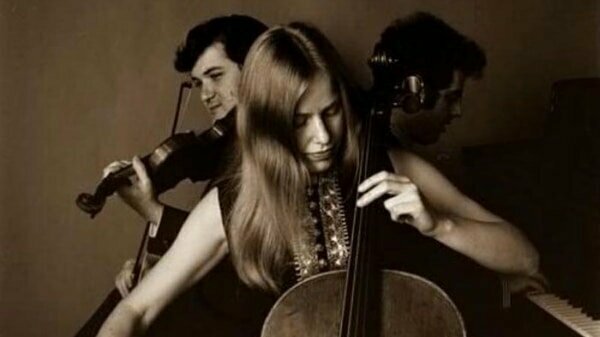

Jacqueline du Pré

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) — Brahms graced us with his brilliant double concerto for Violin and Cello and Orchestra, wonderful chamber music, and also two exquisite cello sonatas. The F-Major Sonata Op. 99 No. 2 is colossal in scope. “Passion rules, fiery to the point of vehemence…” wrote the critic Eduard Hanslick at the time. With its four movements, the sonata breaks into truly romantic music. The impetuous and bold opening well up in the highest stratosphere of the cellist’s range, requires a rich chocolatey tone, a full vibrato, a great deal of energy, and a brilliant pianist! The first movement is followed by a haunting Adagio beginning with pizzicatos after which is the most gorgeous melody ever; then a formidable and tumultuous scherzo turns on its head the expectation this will be a light dance-like movement. But the Rondo finale gives us that long-awaited optimism. The sonata is almost symphonic in scope—especially in this historic larger-than-life performance with Jacqueline du Pré, cellist and Daniel Barenboim pianist—one of the best pieces and performances of cello music ever.

Brahms: Sonata in F No. 2 (Jacqueline du Pré, cello; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) — Without a doubt the Dvořák Cello Concerto in B minor is one of the most brilliant pieces in the cello repertoire. It’s lyrical, rich, and daring. The dramatic and long opening (over three minutes, containing a most beautiful horn solo) sets up the long-waiting cellist for his or her declamatory entry full of brilliant acrobatics you may not expect—chords, double notes, trills, and bouncing bow strokes. Then a simply stunning melodic line enters. Although Dvořák is able to balance a full romantic orchestra with the lone cello, the cellist has to have a huge tone. In three movements, the composer also highlights the horn section throughout. Brahms upon hearing the work said, “Why on earth didn’t I know that one could write a cello concerto like this? Had I known I would have written one long ago.” And truly this piece is one of the first to exploit the range, variety of colors, and the dramatic abilities of the cello.

Antonin Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, B. 191 – I. Allegro (Gregor Piatigorsky, cello; Boston Symphony Orchestra; Charles Munch, cond.)

Antonio Janigro

Richard Strauss (1864-1949) — A symphonic poem or tone poem, a single musical work in one movement or one continuous section, usually depicts a story. Don Quixote Op. 35, subtitled “Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character” interprets the famous novel by Miguel de Cervantes in music. The piece, written in a Theme and Variations form, tells the tale of the errant and befuddled knight Don Quixote, represented by the cello, who travels with his trusted side-kick Sancho Panza, played by the viola, to right the world’s wrongs. An exquisite oboe line portrays Dulcinea the woman Don pines for. The two companions run into all kinds of adventures some comical, some poignant, some dramatic, and some magical. Throughout the piece we examine love and death, and we ask the questions that continue to plague humans—the difference between sanity and insanity; a dream and reality; truth and fiction. Strauss’ instrumentation is masterful. Full of amazing effects, including techniques to depict wind, sheep bleating, pounding timpani, and Strauss utilizes a massive orchestra of winds, brass, and percussion. During the ravishing, melodic lines the cellist impersonates the character who is noble and heroic yet anguished, agitated, and confused. The finale, I believe, is one of the greatest cello melodies ever written. It tears your heart out as you hear Don Quixote accepting his fate, slipping towards death while still clinging to hope for humanity. There are shivers in the strings, and a lone timpani. The piece ends with a quiver, with the cellist sliding slowly down the lowest string disappearing into the abyss.

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Op. 35, TrV 184 – Theme: Don Quixote, the Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance (John Weicher, violin; Milton Preves, viola; Antonio Janigro, cello; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Fritz Reiner, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Op. 35, TrV 184 – Variation 5: The Knight’s Vigil (John Weicher, violin; Milton Preves, viola; Antonio Janigro, cello; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Fritz Reiner, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Op. 35, TrV 184 – Finale: The Death of Don Quixote (John Weicher, violin; Milton Preves, viola; Antonio Janigro, cello; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Fritz Reiner, cond.)

Zara Nelsova

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) — Schelomo Rhapsodie Hébraïque for cello solo and orchestra is based on the biblical story of Solomon, “Vanity of vanities…all is vanity and vexation of spirit.” Schelomo is a sweeping and dramatic one-movement piece. The cello line, the voice of Solomon, is declamatory, brooding, exquisitely lyrical, and rich in texture. Bloch infuses the music with Jewish chant and folk music, and he employs unusual chromaticism, modal harmonies, and changing tempos and meters—a kaleidoscope of exotic sonorities, throbbing accents, waves of sound, and broad phrasing. These techniques allow the soloist freedom to express the great depth of emotion in this piece—the ominous despair as well as the hushed tenderness. The composer, who conducted the debut recording in 1949, chose Zara Nelsova as the cello soloist and she plays with enthralling virtuosity, capturing the haunting and compelling qualities of the piece. But it has been recorded by virtually all the great cellists of our era.

Ernest Bloch: Schelomo (Zara Nelsova, cello; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Ernest Ansermet, cond.)

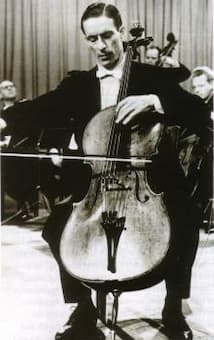

János Starker © i.telegraph.co.uk

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) — Arguably the most significant solo sonata since the Bach Cello Suites, the Kodály Sonata in B minor for Unaccompanied Cello Op. 8 pushes the accepted boundaries of what is possible on the cello. First, it’s written in scordatura tuning. Instead of the usual tuning of the strings C-G-D-A, the two lowest are tuned down to F# and B, creating a special resonance. In three movements and in standard sonata form, this piece is anything but traditional. It’s full of infectious Hungarian rhythms and folk music, while utilizing the entire range of the instrument from the deep low B to extremely high soprano sounds, even off the fingerboard, and techniques such as left-hand pizzicato (plucking) (watch especially in the second movement. It’s really difficult to do!), chords, swift virtuosic passages, pentatonic scales and chromaticism, and effects such as ponticello (an eerie sound produced by playing on the bridge) bouncing bow strokes, and double note trills. My teacher János Starker, who studied the sonata with the composer, made this piece famous, recording it four times. Many other great cellists have recorded it as well, but I’d like to feature a young cellist who plays the sonata—one of the greatest cello pieces ever written—with mesmerizing intensity, masterful virtuosity, and panache: the Swedish cellist (of Hungarian background) Jakob Koranyi. And it’s beautifully filmed too.

Kodály: Sonata in B minor for Unaccompanied Cello Op. 8 (Jakob Koranyi, cello)

Mieczysław Weinberg © Yulia Chaplina, 2019

Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996) — A composer unjustifiably neglected during his lifetime, is today receiving his due. Weinberg’s extensive output of music includes many exquisite pieces including his first cello concerto Op. 43. Born in Poland Weinberg fled Nazi Europe and made his way to the USSR where he made his life and became friends with Dmitri Shostakovich. Weinberg’s music, like Shostakovich’s is compelling, uniquely individual, and expansive. The concerto was premiered by Rostropovich in 1957 but only recently have cellists begun to champion the work. The music is vivid, ardent, and folk-inspired with both Jewish and Polish folk rhythms. It begins Adagio, with a theme that is gripping, mournful, the cello conveying impassioned and transcendent emotions. The dance-like elements appear in the next movements, and then during the final Allegro the opening theme returns, slowly evolving into the major key, moving higher and higher in range to transport us and ending with a sigh.

Mieczysław Weinberg: Cello Concerto, Op. 43 – I. Adagio (Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; USSR State Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

Mieczysław Weinberg: Cello Concerto, Op. 43 – II. Moderato (Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; USSR State Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

Osvaldo Golijov © The Famous People

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960) — Azul for cello, obbligato group, and orchestra by Argentinian composer Golijov, has been described as transcendent, mesmerizing, riveting. Azul meaning blue, the color of the sea, of the sky, is, as The Knights who recorded the album with Yo Yo indicate, “a tool for navigating uncharted waters musically,” of a celestial sense of wonder, and reaching beyond this world. Azul is intended as “a cosmic conversation.” it’s timeless as far as rhythm, and the instrumentation is unique. In four connected movements, interspersed between the solo cello line which sounds improvisatory in this lush score, one can hear the hyper-accordion, bird sounds, full strings and brass, and exotic percussion instruments occasionally imitating crickets. The movements, a poetic opening, an ecstatic slow movement, Transit, Pulsar, Shooting Star, are filled with fantastic effects, folk music, and waves of sound. The cello soloist is called upon to produce distinctive sounds—slides, quarter tones, ghostly unfocused hums, and hollow whistling harmonics. The piece ends with an other-worldly keening and vanishes into space. A wonderful showpiece for the cello, Azul communicates the yearning of our era.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Osvaldo Golijov: Azul (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

Yo-Yo Ma’s Conversation about Creating this Album with Azul

There is definitely the Cello piece of the 20th Century missing from this list and that is John Tavener The Protecting Veil, played sublimely by Steven Isserlis.

where is Schumann?

And where is Shostakovich 1st Cello Concerto?

Where is Hildur. I have listened to many of the pieces presented here and none comes close to Hildur’s bathroom dance from the movie Joker.