Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda published his “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair” in 1924. “Daringly metaphorical and sensuous, this collection juxtaposes youthful passion with the desolation of grief.” It is drawn from the poet’s most intimate and personal associations, and the poems combine “eroticism and the natural world with the influence of expressionism and the genius of a master poet.”

Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair

This collection is one of the best-known works of poetry, and Neruda discloses in his memoires, that although composed in the city, it reflects his childhood in a small Chilean town near the coast. Neruda writes, “This collection is a painful book of pastoral poems filled with the most tormented adolescent passions, mingled with the devastating nature of the southern part of my country. It is a book I love because, in spite of its acute melancholy, the joyfulness of being alive is present in it… It is my love affair with Santiago, with its student crowded streets, the university, and the honeysuckle fragrance of requited love.” In the opening lines of the first poem “Body of a Woman,” we find a twenty-year old poet who “can lead us confidently and lyrically from darkness into the sweet realm of the senses.”

Lars Karlsson: “Body of a Woman” (YL Male Voice Choir; Matti Hyokki, cond.)

Body of a woman, white hills, white thighs,

You look like a world, lying in surrender

My rough peasant body digs in you,

and makes the son leap from the depth of the earth.

I was only a tunnel. The birds fled from me,

and night swamped me with its crushing invasion.

To survive myself I forged you like a weapon,

like an arrow in my bow, a stone in my sling.

But the hour of vengeance falls, and I love you.

Body of skin, of moss, of eager and firm milk.

Oh! The goblets of the breast! Oh, the eyes of absence!

Oh, the roses of the pubis! Oh, your slow and sad voice!

Body of my woman, I will persist in your grace.

My thirst, my anxiety without limit, my undecided road!

Dark riverbeds where the eternal thirst flows

and weariness follows, and the infinite ache.

Andrea Clearfield © Catherine Hennessey

Neruda describes the body of a woman as lying helplessly and vulnerable in surrender. The body is used as a metaphor for the earth and land that subsequently is conquered. The poet compares the conquest of land to the conquest of a woman, presenting the stereotype that women are sexually submissive to men. However, the poet also expresses love in an emotional way, and he conveys the admiration for the beauty of her body. According to a literary critic, “Despite the sexually possessive connotations of this poem, it should be read as an act of love and not as an act of control.”

Andrea Clearfield: 3 Songs for Oboe and Double Bass after poems by Pablo Neruda, No. 1 “Body of a Woman” (Carrie Vecchione, oboe; Rolf Christian Erdahl, double bass)

Donald Grantham

Neruda was frequently asked about the woman in his “Twenty Poems.” He wrote in his memoirs, “It is a difficult question to answer. The two women who weave in and out of these melancholy and passionate poems correspond, let’s say, to Marisol and Marisombra: Sea and Sun and Sea and Shadow. Marisol is love in the enchanted countryside, with stars in bold relief at night… and Marisombra is the student in the city with gentle eyes, the physical peace of passionate meeting in the city’s hideaways.”

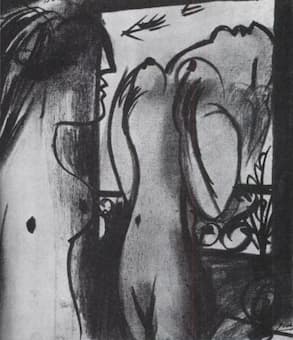

Picasso’s illustration on Pablo Neruda’s 20 poems

Pablo Neruda once remarked, “In the house of poetry, nothing remains except that which was written with blood to be listened to by blood.” There is nothing abstract, idealized or intellectualized in his “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair.” They deal lyrically, expressively, and directly with the tumultuous feelings of men and women in love. Donald Grantham, who studied with Nadia Boulanger for two summers, combined two poems from Neruda’s “Twenty Poems” collection, contrasting the solo violin with a chorus taken from Greek drama.

Donald Grantham: “La cancion deseperada” (Lauren Snouffer, soprano; James K. Bass, bass; Conspirare; Stephen Redfield, violin; Craig Hella Johnson, cond.)

Blas Galindo Dimas

Neruda’s earthy poetry, which chronicled the lives and struggles of ordinary Latin Americans, has always elicited strong responses. But it has gained new currency amid a reassessment prompted by protests by student-led feminists. The controversy focuses on a page in Neruda’s memoir, in which he describes raping a maid in Ceylon, where he occupied a diplomatic post in 1929. Vergara Sánchez writes, “It is time to stop idolizing Neruda and talk about the fact that he was abusive. Just because he is a famous artist does not exempt him from being a rapist.” Isabel Allende, author and women’s rights campaigner adds, “we have started to demystify Neruda now, because we have only recently begun to question rape culture…. Like many young feminists in Chile I am disgusted by some aspects of Neruda’s life and personality, however, we cannot dismiss his writing.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Blas Galindo Dimas: Poema de Neruda (Orquestra de las Americas; Benjamin Juarez Echenique, cond.)