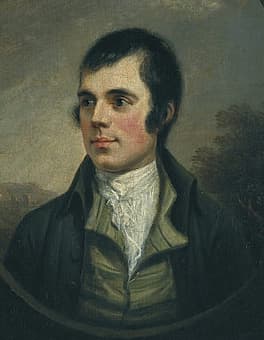

Robert Burns

In 2021 we celebrate the 225th passing of Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet. He died on the morning of 21 July 1796 at the age of 37, and he had been a practicing poet throughout his life. Famous for his rebellion against orthodox religion and morality—attested to by his countless romantic encounters—his poetry celebrated various aspects of “farm life, regional experience, traditional culture, class culture and distinctions, and religious practice.” Burns is considered the conclusion of a long Scottish literary tradition, as the scots vernacular was being replaced by a “shift toward English cultural and linguistic hegemony.”

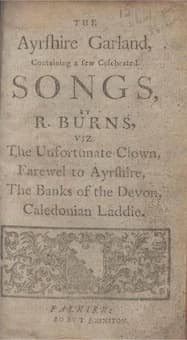

The Kilmarnock publication

Burns was born in Alloway on 25 January 1759, son of a tenant farmer. Growing up in hardship and poverty, he had little regular schooling and was slated to become a full-time farm labourer. He wrote a substantial series of early poems, and considered emigration to the West Indies. In the event, he postponed his planned emigration to Jamaica because the printer John Wilson published Burns’ “Kilmarnock volume,” Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect in 1786.

Ludwig van Beethoven: 25 Scottish Songs, Op. 108 (Renate Krahmer, soprano; Ingeborg Springer, mezzo-soprano; Eberhard Büchner, tenor; Günther Leib, bass; Reinhard Ulbricht, violin; Joachim Bischof, cello; Eva Ander, piano; Leipzig MDR Radio Choir; Horst Neumann, cond.)

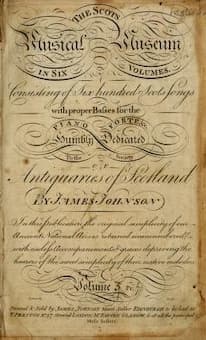

Burns had an intense interest and love for the Scottish countryside, and the oral, musical and literary traditions of its people. He was a man of his time, “and his success as poet, songwriter, and human being owes much to the way he responded to the world around him.” The Kilmarnock publication was the result of two years of scandalous living—he fathered countless children in an era before birth control—and thinking about humanity. Instead of Jamaica, Burns left for Edinburgh and began to consciously participate in the cultural nationalist movement by supplying materials for multi-volume publications edited by music engraver and seller James Johnson and also George Thomson.

Burns had an intense interest and love for the Scottish countryside, and the oral, musical and literary traditions of its people. He was a man of his time, “and his success as poet, songwriter, and human being owes much to the way he responded to the world around him.” The Kilmarnock publication was the result of two years of scandalous living—he fathered countless children in an era before birth control—and thinking about humanity. Instead of Jamaica, Burns left for Edinburgh and began to consciously participate in the cultural nationalist movement by supplying materials for multi-volume publications edited by music engraver and seller James Johnson and also George Thomson.

Birthplace of Robert Burns in Ayr

He drew on a vast store of Scots songs he remembered from his childhood. As he explained, “In my infant and boyish days too, I owed much to an old Maid of my Mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery.”

Benjamin Britten: 4 Burns Songs (Mark Wilde, tenor; David Owen Norris, piano)

The first stamp issued by the Soviet Union in 1956 to commemorate Robert Burns

Burns became an enthusiastic contributor to James Johnson’s “The Scots Musical Museum,” and the first volume published in 1787 included three songs by Burns. For volume two, Burns contributed 40 songs, and he eventually became responsible for about a third of the 600 songs in the entire collection. He also made major contributions to George Thomson’s “A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice.”

As a songwriter, Burns provided his own lyrics and placed words to Scottish folk melodies he collected. He did produce his own arrangements of the music, and that included modifying tunes or recreating melodies on the basis of fragments. Burns explained that he preferred simplicity, relating songs to spoken language, which should be sung in traditional ways. He wrote, “I consider the poetic sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the musical expression, then chose my theme, begin one stanza, when that is composed—which is generally the most difficult part of the business—I walk out, sit down now and then, look out for objects in nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom, humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed.”

As a songwriter, Burns provided his own lyrics and placed words to Scottish folk melodies he collected. He did produce his own arrangements of the music, and that included modifying tunes or recreating melodies on the basis of fragments. Burns explained that he preferred simplicity, relating songs to spoken language, which should be sung in traditional ways. He wrote, “I consider the poetic sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the musical expression, then chose my theme, begin one stanza, when that is composed—which is generally the most difficult part of the business—I walk out, sit down now and then, look out for objects in nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom, humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed.”

Robert Schumann: Myrthen, Op. 25 “Die Hochländer Witwe” (Andrea Lauren Brown, soprano; Uta Hielscher, piano)

Statue of Robert Burns in Dumfies Town Centre

George Thomson, as is well known, commissioned arrangement of “Scottish, Welsh and Irish Airs” from such eminent composers as Franz Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven. These settings in turn, provided the inspiration for composers like Mendelssohn and Schumann, who considered “Burns the representation of the creativity of the peasant Scot, an advocate for all Scotland as anonymous bard.”

The Burns Monument, Alloway

Separating traditional texts from Burns’ work is rather difficult, as many collected original texts were created anew. Burns publically apologized “for many silly compositions of mine. Many beautiful airs wanted words.” However, his short masterpieces on love, the brotherhood of man and the dignity of the common person link “Burns with oral and popular tradition on the one hand and on the other with the societal changes that were intensifying distinctions between people.” His style is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity, yet the strong emotional highs and lows have led to suggestions that Burns “suffered from manic depression.”

The Burns Monument, Calton Hill, Edinburgh

Be that as it may, his health began to fail and he prematurely died of a long-standing rheumatic heart condition in Dumfries. Burns, the struggling farmer and poet became a hero in the eyes of many, as he represented the symbol of every person’s potentiality. He became highly influential in countless parts of the world, and was considered the “people’s poet” of Russia. The Soviet regime considered him “a progressive artist,” and a good many poems were translated into Russian. As such, it is hardly surprising that the musings of the national poet of Scotland have inspired settings from many of the greatest composers through the ages.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dmitry Shostakovich: 6 Romances, Op. 62 (excerpts) (Vassily Savenko, bass-baritone; Alexander Blok, piano)

What about the songs of Carl Maria von Weber. I have the EMI recording of Tenor Robert White singing this and Beethoven. Brilliant recording with chamber instrument accompaniment.