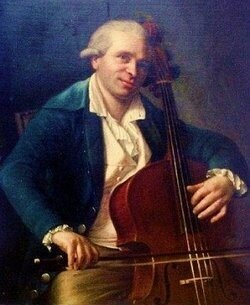

Jean-Louis Duport

Desert Island? No problem. I’d take the five Beethoven Cello Sonatas hands down. Spanning all three periods of Beethoven’s life they essentially depict his whole life story — from the lyrical Sonata in F major Op. 5 Nr. 1 to the grandiose Op. 102. Nr. 2 in D major. The works are a staple of the cello repertoire.

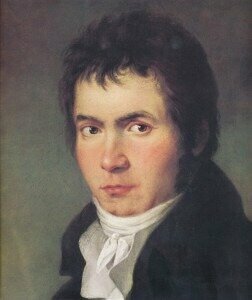

In 1796, twenty-five year old Ludwig van Beethoven embarked on a five-month concert tour performing as a pianist. He had not yet lost his hearing. The tour included performances in Berlin at the court of King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, who was a music lover and an amateur cellist. In fact, both Haydn and Mozart wrote string quartets for King Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Beethoven encountered two brilliant cellists there — the Duport brothers, Jean-Pierre and the younger Jean–Louis. The Duport brothers are still talked about today for several reasons! Of the younger Duport’s playing the famous French philosopher and writer Voltaire said, “Sir, you will make me believe in miracles, for I see that you can turn an ox into a nightingale.”

No doubt you cellists like me, have struggled with Jean-Louis Duport’s twenty-one thorny etudes — “The Art of Fingering and Bowing the Violoncello,” (Jean-Pierre actually wrote two of studies in the volume) and today it’s still our bible of cello technique along with the studies of Popper.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Duport owned a 1711 Stradivarius cello. None other than Napoleon insisted on trying the cello saying, “How the devil do you hold this thing, Monsieur Duport?” It is said that to Duport’s horror, Napoleon made a small dent in the ribs of the cello, which still can be seen on the Duport Strad today. (Most recently, Mstislav Rostropovich owned the instrument.)

Beethoven was so impressed by the music making of the Duport brothers that he decided to write two cello sonatas for them — the Sonata in F and the Sonata in G minor, which were performed at the court in Berlin in 1796, with Beethoven at the piano. There is some debate as to whether it was Jean-Louis or Jean-Pierre who performed the cello part.

These beautiful early sonatas are tours de force for the piano. Although there are gorgeous melody lines for the cello, accompaniment figures abound while the piano waxes eloquent. At the time the sonatas were considered works for piano and cello. Beethoven’s two early sonatas are still characteristic of the music of Haydn and Mozart in structure and content.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5, No. 1 (Juris Teichmanis, cello; Hansjacob Staemmler, fortepiano)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 5, No. 2 (Jorg Ulrich Krah, cello; Bernhard Parz, piano)

Both of these early sonatas begin with short slow introductions followed by what was considered virtuosic writing for the cello. Up to this time the cello had been treated as a bass instrument. Beethoven’s characteristic accents on the off beats are already evinced in these early works.

In 1802 Beethoven was despondent about losing his hearing. His performing career was doomed. In a letter Beethoven bemoaned his tragic affliction:

“But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended me life — it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me…” Heiligenstadt Testament

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69 (Maria Kliegel, cello; Nina Tichman, piano)

Despite his anguish, Beethoven was very productive in this, his middle period, composing the Violin Concerto, his Trios Op. 70— The “Ghost” and The “Archduke” for piano, violin and cello, and the monumental Fifth Symphony and Sixth Symphony, “The Pastoral.” The Cello Sonata in A Op. 69 was composed in 1808 when Beethoven was virtually deaf. The work is a masterpiece and is perhaps the most beloved of his cello works.

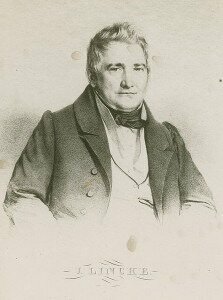

Joseph Linke

The cello and piano are treated as equals in this sonata and as such it is the first true piece of chamber music. Unusually, the cello begins the sonata alone. Throughout, there are little ornamental bits marked “ad libitum,” to be performed at the liberty of the player. Beethoven uses forceful accented rhythmic patterns in the demonic Scherzo, keeping everyone guessing as to what the meter is. Also of note is the fact that the brisk last movement requires the cellist to play in the stratosphere — the high range of the instrument, which shows off the technique of the cellist. Beethoven develops the melodic and harmonic realms in a way that is architecturally much more spacious and expansive than previous compositions. Beethoven dedicated this sonata to his friend Ignaz Gleichenstein who played the cello well. Baron Gleichenstein had taken over running Beethoven’s affairs when Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s former student and personal assistant, left Vienna in 1805.

Although all the most accomplished cellists have recorded this sonata, one of my favorites is the inspired interpretation of Glenn Gould and Leonard Rose.

The last two cello sonatas came about in a way that is worth noting. In 1808, Count Razumovsky (to whom Beethoven had dedicated his Op. 59 string quartets) asked violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh to form “the finest string quartet in Europe.” Schuppanzigh invited cellist Joseph Linke to join the quartet. Linke was known for his melodious, expressive phrasing and impeccable technique. They played many of the first performances of Beethoven’s string quartets and Linke, Schuppanzigh, and Beethoven presented the premiers of the two piano trios that year at the home of Countess Maria von Erdödy. Then in 1814, a fire completely destroyed Count Razumovsky’s palace. The quartet lost their patron. Countess Erdödy, Beethoven’s benefactress, agreed to employ Linke. During the summer of 1815 the Countess and her husband took their summer sojourn at their home on the Jedlersee. Although Beethoven joined them there briefly he did not know that soon the Erdödys and Linke would leave for Croatia.

Cello Sonata No. 4 in C Major, Op. 102, No. 1 (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Emanuel Ax, piano)

Cello Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102, No. 2 (Kristina Blaumane, cello; Jacob Katsnelson, piano)

The fourth and fifth cello sonatas in C major and the D major respectively, Op. 102, were written as a farewell to Joseph Linke.

The sonatas mark Beethoven’s late period. Although these are shorter sonatas than the first three, they are deeply spiritual, more experimental and dramatic. The C major sonata begins once again with the cello alone in a markedly vocal and expressive way. Although it is hard to pick one, this sonata might be my favorite!

Beethoven’s heroic later works are generally characterized by a sense of urgency, struggle, and triumph. This is evinced in the last sonata in D major. This sonata has the only complete slow movement of the five sonatas. It is full of pathos and passion. A grandiose fugue ends the piece. (A link to the great cellist Emanuel Feuermann playing the fugue is below.)

Beethoven’s cello sonatas, the ten sonatas for violin and piano and the masterful piano sonatas possess the force of intensity and range of expression beyond any of Beethoven’s predecessors. Beethoven succeeded in raising instrumental music to the highest levels of art. I never tire of playing or hearing them.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Emanuel Feuermann excerpt from the D major sonata (the fugue)

This was a private recording of the end of this work from a broadcast from New York’s Town Hall. The audio quality in this excerpt is not ideal, but given the historic nature of the broadcast and the fact that there is no other recording of Feuermann in this repertoire.

Quite a good article. One inaccuracy: the dedicatee of the op. 5 sonatas was King Friedrich Wilhelm II, not Friedrich II. It’s an important distinction: Friedrich II was Friedrich Wilhelm’s predecessor and uncle, known in English as Frederick the Great. He played the flute, not the cello.

Thank you Michael 🙂

Thanks for the article. For those who haven’t heard of it, try ‘Beethoven’s Cello’ by Marc Moskovitz and Larry Todd.

Thank you Janet for bringing these extraordinary pieces back into my consciousness. And for setting them in context with your fascinating article. I last heard the cello sonatas as a student in the 1970s. I found them all marvellous but the late ones so emotionally overwhelming that I had to put them on one side or I would never have done anything else, like getting an essay written. I can’t believe how familiar they sound to me now after 45 years not listening to any classical music at all. And I’m in tears again! What better choice indeed for your desert island discs, and thank you for sharing them here, all with different musicians too. How do they manage to keep playing, and with such exquisite control and sensitivity?!