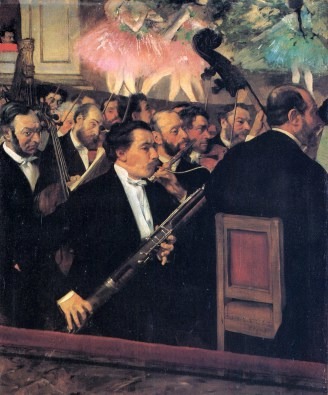

Orchestra of the Opera by Edgar Degas

The nice thing about going to an opera performance is that you get to have fictional dates with characters your mom would almost certainly disapprove of. Take for example Robert le diable (Robert the Devil), an opera in five acts composed by Giacomo Meyerbeer. The libretto was written by Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne, and loosely follows the legends of Duke Robert the Magnificent of Normandy, alleged to have been the son of the Devil. I am sure his real father William the Conqueror would not have been pleased! Meyerbeer originally planned the work as a comic opera, but in order to concentrate more on the sensational storyline of Robert’s diabolic ancestry, changed the format to meet the requirements of the Paris Opera. In the end, it turned into a grand opera in five acts and seven scenes, sporting a remarkably colorful orchestra and a number of ballet episodes.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: Robert le diable, “Nonnes qui reposez” (The nuns are resting)

The immediate success of the opera was breathtaking! It was considered a “remarkable work in the history of art,” and it placed Meyerbeer at the head of European opera composers. Richard Wagner delighted in the “almost sinister and deathless atmosphere,” and Frédéric Chopin, who was in the audience during the premiere wrote, “If ever magnificence was seen in the theatre, I doubt that it reached the level of splendour shown in Robert…It is a masterpiece…Meyerbeer has made himself immortal.” A number of composers, including Thalberg, Herz, Kalkbrenner and Liszt, immediately took advantage of this operatic success and produced countless arrangements, variations and fantasies based on melodies from the opera. Not to be outdone, Frédéric Chopin composed his own homage for cello and piano in 1832.

Frédéric Chopin: Grand Duo on themes from Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable

Giacomo Meyerbeer

Credit: http://www.thecultureconcept.com/

Meyerbeer first met Richard Wagner at a spa in Boulogne in 1839. Young Richard was at the beginning of his career, and unabashedly asked for money and professional recommendations. Meyerbeer obliged, and without his support early productions of Rienzi and the Flying Dutchman would not have been possible. When Meyerbeer learned that Wagner was making slanderous remarks behind his back, “as a Jew, Meyerbeer has no mother tongue, no speech inextricably entwined among the sinews of his inmost being,” he naturally withdrew all support. Wagner was also unhappy that Meyerbeer was offered the post as Prussian Generalmusikdirector in 1842. As a court composer, Meyerbeer produced music for official court entertainment and royal family occasions. For example, the Fackeltanz (torch-dance) No. 1 was composed for the wedding of Princess Marie in 1844.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: Fackeltanz No. 1 in B-flat Major

Meyerbeer’s youngest brother Michael Beer was the author of a number of dramas, including the play Struensee. Set at the Danish court, the play was banned in Berlin for nearly twenty years because it might have offended Danish Royalty. After the ban was lifted in 1846, Amalie Beer wanted to see the play of her youngest son performed on the court stage together with music by her eldest son. Giacomo set to work and composed incidental music for the play, yet he dejectedly reported after the premiere “During the entr’acte music a large part of the public did not listen; they talked loudly among themselves.” Clearly, Meyerbeer had more enemies than supporters in Germany!

Giacomo Meyerbeer: Struensee, “Overture”

Please join us again next time when we explore Meyerbeer’s greatest successes on the Parisian operatic stage!