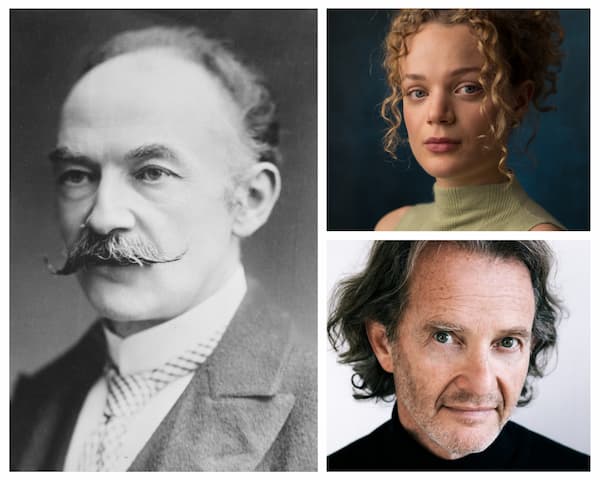

Warren Mok and Yuki Ip (from right) as Sun Yat-sen and his first wife Lu Muzhen in the opera Dr. Sun Yat-sen. Credit: Opera Hong Kong

Hong Kong made history this month, hosting the world premiere of the former colony’s first homegrown grand opera, “Dr. Sun Yat-sen.” Not only is its namesake Cantonese; so were the composer, librettist, and much of the cast. Opera Hong Kong’s first-ever original commission, “Dr. Sun” was accompanied by the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra, an ensemble of traditional instruments known for tackling contemporary works.

But by the time the curtain rose on Oct. 13, “Dr. Sun” was best known for offstage drama: a version with Western-style instruments was due to serve as world premiere in Beijing in September, but the performance was abruptly called off amid suspicions of censorship. The controversy raised Hong Kong’s profile in global music circles, which have often looked to mainland China’s booming growth in classical music to offset declining interest in the West. While China has played host to many international collaborations in opera and other musical genres, “Dr. Sun Yat-sen” was the biggest-ever original work to draw on non-mainland Chinese talent and tackle themes from Chinese history, fueling speculation that its Beijing cancellation was linked to Party sensitivities over the portrayal of historical events. Despite the withdrawal of the Hong Kong premiere’s sponsor, Swiss watchmaker Carl F. Bucherer, Opera Hong Kong’s board of directors and other supporters stuck with the production through opening night. Its premiere was an accomplishment; but the warm reception of such an unconventional work by Hong Kong audiences was a minor miracle.

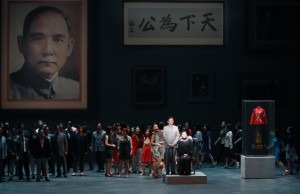

Tenor Warren Mok as Sun Yat-sen (center), followed by soprano Yao Hong as his wife Soong Chingling, return to a hero's welcome in Act III of the opera Dr. Sun Yat-sen. Credit: Opera Hong Kong

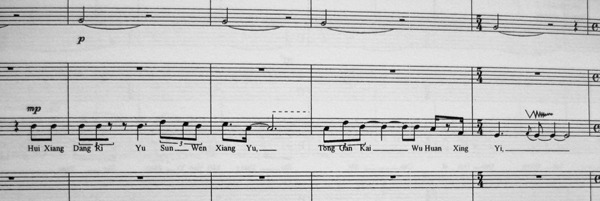

An excerpt from Huang Ruo's score, with dashed and zigzagging lines indicating where Western-trained singers should insert traditional Chinese opera vocal technique.

The libretto, by Hong Kong playwright Candace Chong, focuses on Sun’s stormy private life with language that alternates between poetic phrases and vernacular Mandarin. “I felt it could have been more poetic and less colloquial overall,” said a local listener. “In Chinese opera, we are accustomed to hearing people speak ‘normally’ in a poetic way, and it might have sounded more beautiful without feeling unnatural to a Chinese audience.” It could even, she felt, have been sung entirely in Cantonese, instead of a single duet between Sun and his imminently-ex wife. Spoken English interludes, which support a plot device, interrupted the dramatic flow and could stand to be trimmed or dropped altogether.

Epilogue of Dr. Sun Yat-sen.

Credit: Opera Hong Kong

Besides a garish Sgt. Pepper’s-style outfit for Sun in Act III, costumes and sets did their job cleanly and superbly.

Yao Hong (sitting, right) as Soong Chingling and Warren Mok (standing, left) in the title role of Dr. Sun Yat-sen. Credit: Opera Hong Kong

For a new opera premiering under adverse circumstances, “Dr. Sun Yat-sen” compared favorably to recent outings operatic outings drawn from Chinese tales and talent, notably Tan Dun’s “First Emperor” and the Stewart Wallace’s “The Bonesetter’s Daughter”. Like New York, Hong Kong’s strong financial industry can support major artistic experiments, while the territory’s freedoms continue to give haven to interpretations of Chinese history and identity beyond Beijing’s orthodoxies. For the novelty, scandal, and music alike, this was an experiment well worth watching, and repeating.