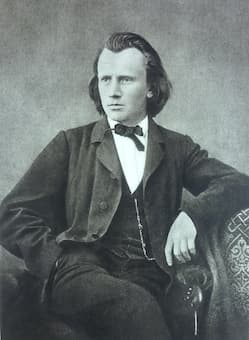

Johannes Brahms in 1866

In 1777, the German poet Johann von Goethe was traveling in the Harz mountains in the winter. He ascended the Brocken, the highest peak in the Harz, arriving at midday, and gazed out on a white world, with the landscape below him obscured in cloud. The trees at the summit would have been cloaked in snow, forming hulking shapes against a brilliant blue sky. Goethe used the experience as the inspiration for his poem Harzreise im Winter (Winter Journey in the Harz).

The poem is 88 lines of free verse set as 11 stanzas of differing lengths. The poet imagines himself as a vulture, hovering above the earth. The next 4 stanzas use the landscape to describe those who are lucky and those who suffer from misfortune. From this external view point, the poet next looks inside himself to see distress and hate and asks how it can be relieved. Invoking the ‘Father of Love’ and the ‘Brothers of the Hunt,’ the poet/traveller seeks to clear himself of pain. At the end he reaches the summit and, gazing about, sees how the spectacle of nature outweighs all these considerations. Metaphorically, the poet ascends the mountain to confront the oracle of nature about his own fate: condemned to a difficult life or could he be redeemed by love?

Julie Schumann (1845-1872) at age 21

Brahms took three stanzas of the poem and set it as his Rhapsodie für eine Altstimme, Männerchor und Orchester, more commonly known as the Alto Rhapsody, in 1869 for the marriage of Robert and Clara Schumann’s daughter Julie.

Julie lived in the south with friends of her mother’s as her health was delicate. That’s where she met Count Vittorio Amadeo Radicati di Marmorito, who she married in 1869. Brahms was at the wedding as the man of honour. Julie died in 1872 in her third year of marriage at the birth of her third child.

Of Goethe’s original 11 stanzas, Brahms chose to set stanzas 5, 6, 7, the core of the poem where he changes from external observation to internal examination. He starts his setting in medias res, in the middle of things, with the word ‘Aber,’ (But). It’s a curious text because we start with the poet / Brahms disappearing into the bushes, which then obscure his track. The next verse may also be describing Brahms’ feelings at Julie’s marriage to an Italian nobleman, when he himself may have had aspirations for her hand. The final verse is the summons of the Father of Love to help the poor poet (or Brahms) regain his peaceful state of mind where all the possibilities open before him.

Aber abseits wer ist’s? | But who is that apart? |

Im Gebüsch verliert sich sein Pfad; | His path disappears in the bushes; |

hinter ihm schlagen die Sträuche zusammen, | behind him the branches spring together; |

das Gras steht wieder auf, | the grass stands up again; |

die Öde verschlingt ihn. | the wasteland engulfs him. |

|

|

Ach, wer heilet die Schmerzen | Ah, who heals the pains |

dess, dem Balsam zu Gift ward? | of him for whom balsam turned to poison? |

Der sich Menschenhaß | Who drank hatred of man |

aus der Fülle der Liebe trank! | from the abundance of love? |

Erst verachtet, nun ein Verächter, | First scorned, now a scorner, |

zehrt er heimlich auf | he secretly feeds on |

seinen eigenen Wert | his own merit, |

In ungenügender Selbstsucht. | in unsatisfying egotism. |

|

|

Ist auf deinem Psalter, | If there is on your psaltery, |

Vater der Liebe, ein Ton | Father of love, one note |

seinem Ohre vernehmlich, | his ear can hear, |

so erquicke sein Herz! | then refresh his heart! |

Öffne den umwölkten Blick | Open his clouded gaze |

über die tausend Quellen | to the thousand springs |

neben dem Durstenden | next to him who thirsts |

in der Wüste! | in the wilderness! |

Grace Hoffman in 1966

Each verse is set in a different style: the first is a chromatically wandering piece for the soloist and the orchestra, the second verse is really an aria for the singer, and it is only in the third verse, which is stylistically like A German Requiem, that the male chorus enters.

The first performance was for soloist and accompaniment (whether orchestra or merely piano is unclear) in 1869, with only Robert and Clara Schumann in the audience. Its first public performance with soloist, male chorus, and orchestra was in 1870 in Jena, with French mezzo Pauline Viardot as soloist.

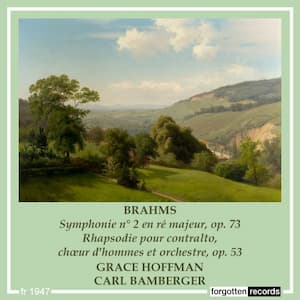

Johannes Brahms: Alto Rhapsody

Carl Bamberger

This 1956 performance with the Choir and Orchestra of North German Radio, Hamburg, was with soloist Grace Hoffman and conductor Carl Bamberger. The American mezzo Grace Hoffman was based at the Staatsoper Stuttgart from 1955 to 1992, with one of her signature roles being Wagner’s Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde. Carl Bamberger was born in 1902 in Vienna and died in 1987 in New York. He was a student of the music theorist Heinrich Schenker in Vienna but abandoned his studies in 1924 to become a conductor. He emigrated to the US in 1937 where he led the orchestral and opera departments of the Mannes Music School in New York. His wife, Lotte, and his sister Gerty also taught at the school.

Performed by

Performed by

Grace Hoffman

Carl Bamberger

Choir and Orchestra of North German Radio, Hamburg

Recorded in 1956

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter