Glenn Gould’s iconic stature as one of the great if not the greatest pianists has not diminished since he passed in 1982 shortly after his 50th birthday. Many of us know him for his recordings of Bach, especially the Goldberg Variations, and that he shunned live performance. We imagine him as a reclusive, inscrutable, almost mythical figure. Indeed, he was a private person, but his youth was colorful and fascinating.

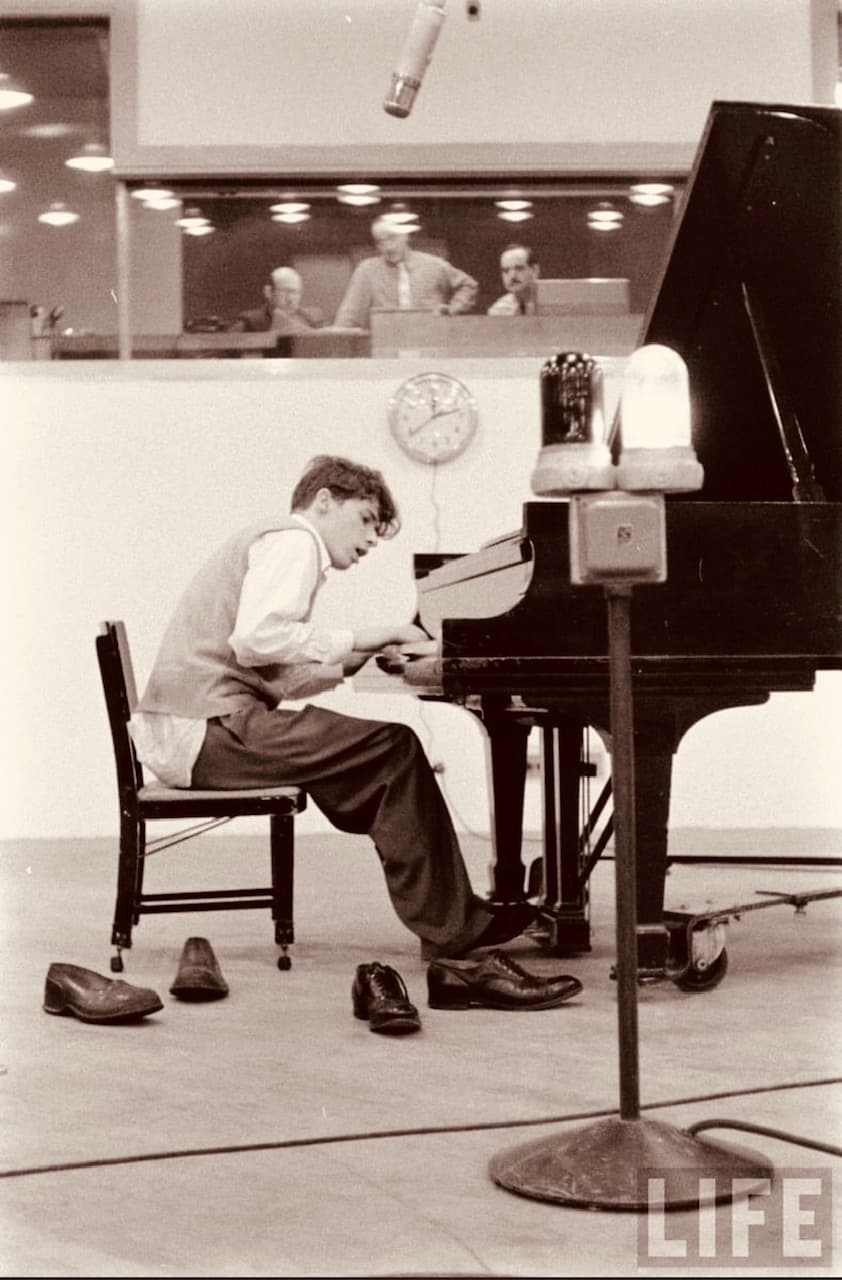

The young Glenn Gould in a recording session

Born in 1932, an only child, he learned to read music before he could read words. His parents dedicated their lives to this surprise late birth and his mother taught him. He was already playing at the age of 3 or 4. Gould played all the music of composers one would expect: Liszt, Chopin, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and of course Bach. During his days of glory, as he called it, at the age of 12 or 13, Gould even played all Chopin and Liszt programs. When Gould was 14 years old, he performed Beethoven Concerto No. 4 with the Royal Conservatory Orchestra in Toronto led by conductor Victor Feldbrill. “Out came this gangly kid with the reputation of a child prodigy.” He said, “We’d never seen anyone sit at the piano in that position. But his playing and musicianship were unmistakable. He shined a new light on the Beethoven.”

By the age of 16 Gould shied away from romantic music and he turned his interest toward orchestral repertoire especially works of composers of the twentieth century such as Wagner, Strauss, Mahler, and Schoenberg who didn’t write for the piano. Gould would compose his own transcriptions. According to Gould’s closest friends, he would play these works for his own enjoyment and practice very late at night singing at the top of his lungs as if in a trance.

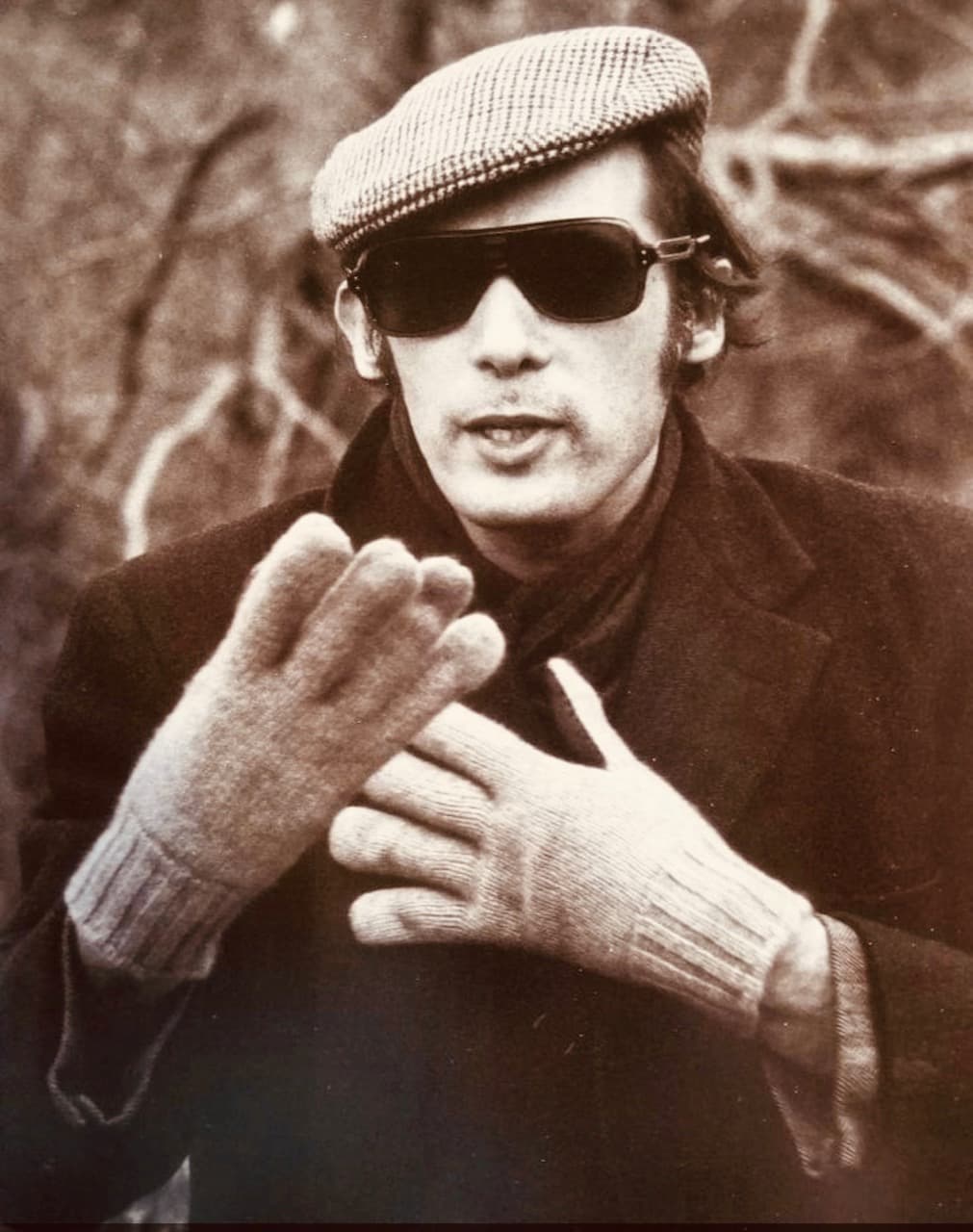

Glenn Gould with his gloves

He studied with Alberto Guerrero who sat low at the keyboard, and Gould was instructed in Guerrero’s signature method— tapping fingers without lifting them, in other words employing a detached finger technique. The astonishing clarity of Gould’s playing was his trademark. He played with tremendous exuberance, attentiveness, and fearlessness yet somehow maintained a spontaneity that we can only marvel at. Gould went everywhere with a special rug and chair made by his father. Initially, his father sawed off the legs of chairs until he finally designed a chair that was 13 inches from the floor. Perhaps his unconventional posture also stems from the fact that Gould performed mainly in Toronto for CBC radio in their studios, where he could be uninhibited. He seldom attended concerts and thus Gould had no example of traditional onstage “deportment.” Throughout his life, he remained uncomfortable in crowds of people.

Gould’s protected his privacy. He enjoyed sequestered, rural living, his main companion was his dog, and he lived on Lake Simcoe, near Orillia, Ontario, where he had the time to study in idyllic surroundings. Those who knew him say he had a wonderful and even wacky sense of humor, and he could be seen bundled up, singing and conducting even while driving his boat. He did have normal relations with women. Fran Barrault a teenage girlfriend moved nearby and fell in love with the handsome young man. Glenn enjoyed her Chickering Grand piano, which he practiced for hours as he prepared for his 1955 New York debut. The concert resulted in a recording contract with Columbia.

Off the Record 30-minute film

“What do you want to record first?” Asked the recording engineer. When the 22-year-old Gould responded, “The Goldberg Variations”, the Columbia executive was nonplussed. This work had rarely been recorded. It was considered esoteric and demanding technically. The executive rejoined, “Wouldn’t the inventions for a young chap like you be more fitting?” Gould didn’t budge and his playing was mesmerizing. “Who IS this guy?” they wondered. The eloquence and thoughtfulness of Gould’s playing was nothing short of phenomenal. The debut recording, made in 1955 at Columbia Records in Manhattan over four days in June became a bestseller.

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Aria (Glenn Gould, piano)

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 1. a 1 Clav. (Glenn Gould, piano)

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 2. a 1 Clav. (Glenn Gould, piano)

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 12. Canone alla Quarta. a 1 Clav. (Glenn Gould, piano)

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 29. a 1 o vero 2 Clav. (Glenn Gould, piano)

Glenn Gould with his dog, Nick

Due to his striking appearance and personality, as well as his wonderful reviews in all the papers even Vogue and Life Magazine, as well as the astonishing record sales, he became the darling of the media in the 1950s, his coats and gloves, his avoidance of handshaking, his cancellations of performances notwithstanding.

In 1957 Gould embarked on a European tour of Germany, Austria, and Russia. The first Canadian artist to go to Russia during the Cold War, he performed 8 concerts in two weeks. Initially, the hall was half empty. Russians revered Bach but it was rarely performed especially in a big hall and Gould was an unknown artist. During the intermission, audience members rushed to the phones to call their friends to tell them “A genius” was performing. By the second half of the concert, the hall was filled! The pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy attended, and he exclaimed that it was an extraordinary event. Gould played contemporary music not often heard in Russia such as early Berg and Hindemith, as well as Beethoven, Brahms, and the not-so-familiar Goldberg Variations. Vladimir Ashkenazy recalls Gould’s performance of Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 2, which was recorded live to a full house, with over 1100 audience members standing at the back. It was perfect and convincing playing.

Radio Interview

This was followed by a 1959 tour with 55 concerts, but Gould never enjoyed touring. He hated the unfamiliar pianos, unfamiliar conductors, and unfamiliar hotel rooms. He found it hideous and a great strain to perform a concert every second or third day. But his frustration went beyond physical disquiet. He felt that touring instills conservatism artistically. Because of the “non-take-twoness” or the inability to repeat a passage, the fear of trying anything new can become ingrained.

At home with Glenn Gould 1959 1/9

2/9

Gould sought to play differently each time. “Why repeat what everyone does or even what I did before?” he would say. The infamous New York Philharmonic appearance with Leonard Bernstein is a case in point. Gould performed Brahms Piano Concerto No 1. To call it “Unorthodox” is an understatement. Bernstein felt he had to address the audience with a disclaimer. “Who is the boss, the soloist or the conductor?” He asked. Although Gould’s interpretation was new and incompatible, Bernstein, a composer and wonderful pianist himself, felt he must take seriously anything Gould conceived in good faith. He understood Gould’s genius. Backstage, Gould could hear the commentary. Bernstein, Gould felt, spoke with the best of intentions and a generous spirit. He said he sat backstage “giggling. I thought it was delightful.” Nonetheless, there were howls of derision from the critics and the concert was talked about for months.

Gould retired from the concert stage at the age of 31, his final concert on April 19, 1964. He felt his audience could be larger through recording and that in his mind it was a step forward. Gould wanted to do other things such as producing shows, and scripts, and radio documentaries that were commentaries on the human condition.

Glenn Gould’s 1/6 1968 Concert Dropout

Shortly thereafter, his long phone conversations with Cornelia Foss, the wife of conductor, composer, and pianist Lucas Foss, resulted in an amorous liaison. Cornelia had every intention of marrying Gould. Devoted to her and to her children, Gould was warm and sweet, and caring. Photos from 1968 show a chic couple. He and the children loved romping with Gould’s collie and going on road trips, but as the years passed Gould became increasingly paranoid. He took medications for depression and anxiety, mixing them indiscriminately and his increasing hypochondria and eccentricities intensified. Glenn was devastated when Cornelia left him. She and her children had lived with him from 1968-1972. He would never again have such a close relationship.

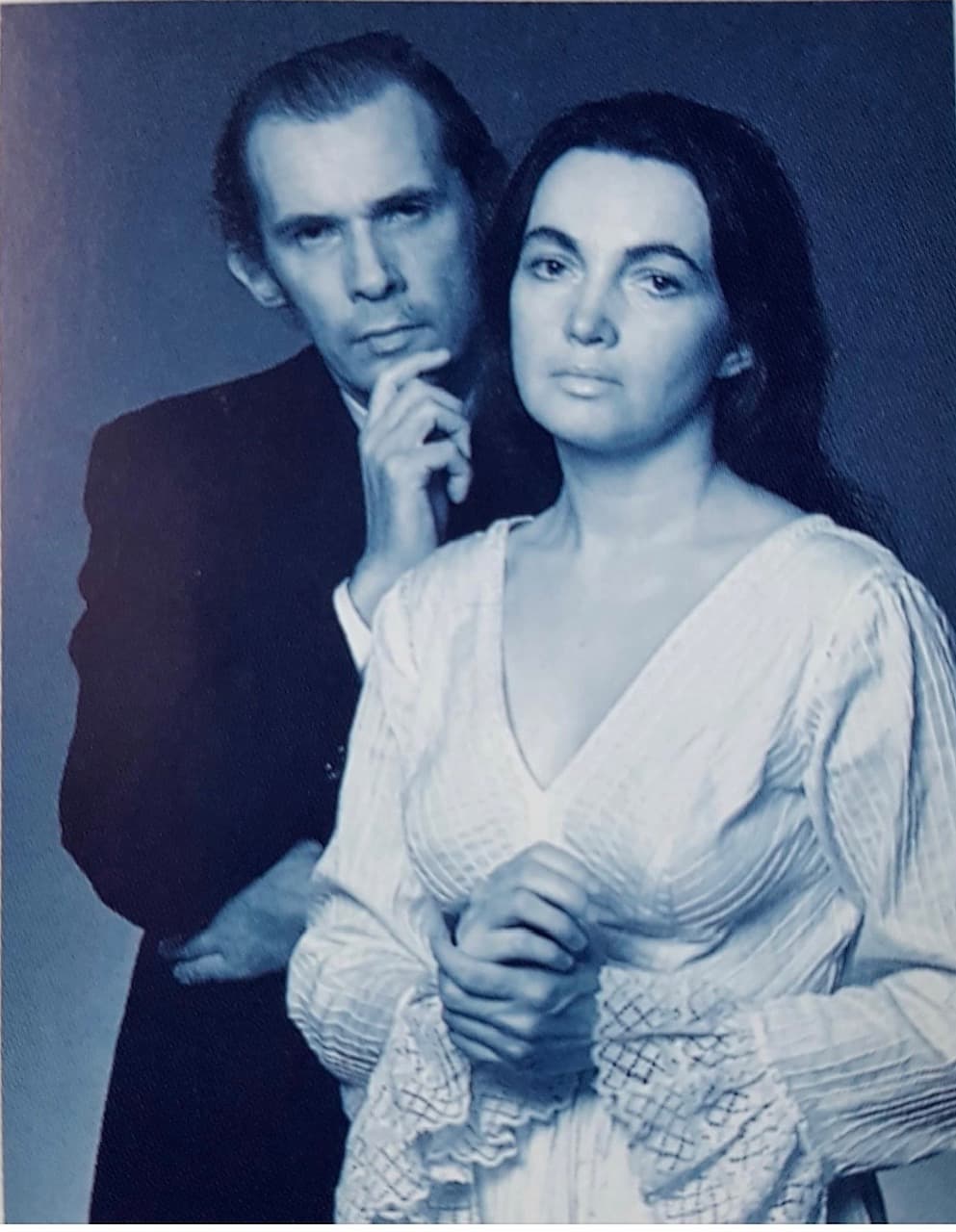

Glenn Gould with soprano Roxolana Roslak

An innovator and proponent of recording and broadcasting technologies, Gould forecast what is available today. He continued to hate going to New York, so he created a remote recording studio in Toronto outfitted with the best microphones and grand pianos available. CBS paid him to record in Toronto. The makeshift studios were in the auditorium on the seventh floor of the old Eatons department store where the recordings of the Bach Six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord with violinist Jamie Laredo took place. Laredo recalls recording after hours usually from 11:00 pm until 4:00 or 5:00 am in the warm acoustics.

On the record 30-minute film

Gould recorded with the eminent and glamorous Canadian soprano Roxolana Roslak. Born in Ukraine, she made her Canadian Opera Company debut in 1963. After television appearances in 1975 with Gould, they recorded Hindemith’s Das Marienleben. Theirs was a special and likely romantic relationship.

Throughout his life, Gould received deeply touching letters—letters of gratitude from audience members and letters from people who were lonely or unhappy and who experienced consolation from his music. Gould reveled in touching people’s hearts and minds. He still commands a huge following—and still kindles controversy. Most artists who have attained a certain fame cannot imagine relinquishing it all. Perhaps our fascination with Gould is tinged with envy. Gould remains an icon and an example of an artist who lived unfettered by convention.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

A brilliant genius who lives forever through matchless recordings, Glenn Gould is remarkable.

I totally agree with you.