Janet’s Father

It was early 2009 and I was searching for a way to distract my father and myself after the recent death of my mother.

My father loved to “talk shop.” Little did I know that I would stumble upon an amazing story by asking an innocent question.

My father played with all the greatest conductors including Arturo Toscanini, Sir John Barbiroli, Sir Thomas Beecham, István Kertész and others, but I had never asked him about Leonard Bernstein. “Dad,” I said, “did you ever play with Leonard Bernstein?” My father’s eyes glazed over. He seemed to withdraw into the recesses of memory. He put the palm of his hand to his face and we were suspended in time for several moments. What had I unearthed?

Suddenly he exclaimed, “Yes! It was a very hot day. It was with the Jewish orchestra in the D.P. camps! (Displaced persons) He conducted. He played Rhapsody in Blue on the piano. It was fantastic! We were just kids.”

Several moments passed as I reeled in shock. Sixty years of professional cello playing between us, and he had never told me this story. My father recalled the entire program. It opened with the Overture to the opera Der Freischütz by Carl Maria von Weber and excerpts from Bizet’s L’Arlésienne Suite. There had been a young girl who sang arias from the operas Rigoletto and Tosca and a 19 year-old solo violinist with stunning talent who played Tartini’s G minor sonata.

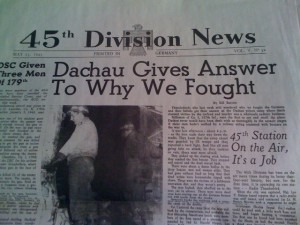

I raced to my computer and Googled Bernstein’s website. Yes there it was; May 10th, 1948, Bernstein had conducted an orchestra in two D.P. camps near Munich — a tiny group of seventeen musicians, all survivors of the Holocaust.

These musicians who had suffered themselves, attempted to boost morale for those languishing in the camps, who were waiting for documents to leave Europe and who desperately waited for word of loved ones. But countless numbers had perished without a trace. The music brought solace to the survivors; wordlessly expressing that perhaps life could still offer beauty and hope.

I began to research this information. Thanks to the Internet I discovered that there had been a printed program of the performances with Leonard Bernstein and that it is housed at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. I wrote a detailed email to the archivist excitedly inquiring if on my next orchestra tour to New York I could come to see the program. The archivist responded immediately. She indicated that I could make an appointment anytime to see the program, but didn’t I want to see the live video testimony and the photographs? Photographs! Perhaps my father was in them.

I waited for the weeks to go by impatiently. In May 2009 the Minnesota Orchestra was scheduled to play a “run out” concert to Carnegie Hall — one day in New York. We would fly in, rehearse during the afternoon of the following day and fly back home after the concert that same evening – precious little time to race down to the museum.

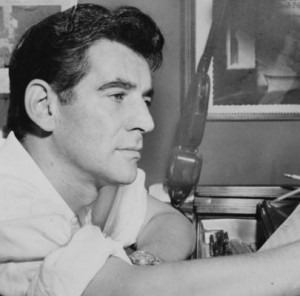

I rose very early to get to the museum. I was greeted by a diminutive lady with a shock of white hair and ushered into her cluttered office — little more than a cubbyhole. She opened an archival box with gloved hands carefully pulling out four tiny black and white photos. There was no doubt — my dad looking dapper, with a full head of hair and a mustache stood shyly with the group and Leonard Bernstein. I welled up when the archivist wrote my father’s name — George Horvath, Toronto, Canada on a photocopy of one of the pictures.

I then viewed the video testimony — the reminiscences of the young singer on the program towards the end of her life. My tears came in earnest when she sang, transporting me to another dimension. While I watched the video, the archivist made a telephone call. “Rita. There’s some lady here from Minneapolis watching your mother’s testimony. I thought maybe you should contact her!”

I noticed the clock. I had to leave in order to make my rehearsal. As I raced into Carnegie Hall, Rita Lerner called me. Our connection was immediate. She told me that her mother had been the singer in the little Jewish orchestra and that the parents of her cousin Sonia Beker, were also members of the ensemble.

I was astonished when they told me that this small group of musicians performed not two but 200 concerts in 100 D.P. camps all over Bavaria from 1945-1948. They were bussed twice weekly and paid in American canned goods and much needed food. Sonia wrote a book about the group entitled Symphony on Fire and a documentary was filmed based on the book. Photos of my dad appear in them.

Sonia and Rita promised to send the book, additional photographs and the documentary to me. I eagerly anticipated viewing them with my father.

When the photos arrived I enlarged them to poster size hoping that my father would be able to identify some of the other members. In August I travelled to Toronto to show my father these precious artifacts. We viewed the documentary together holding hands. I squealed each time he appeared in the documentary. “Dad there you are!” All he could do was shake his head and say with incredulity, “Janetkém, that’s me! How did you find this?”

The months of research paid off in a very meaningful way. My tireless efforts to uncover this story finally spurred my dad to share his Holocaust experiences with me only weeks before he passed away in November of 2009.

Beautiful story, Janet. Hope things are well in Minneapolis, if you’re there. I know Tony Ross and Stephanie Arado, who have connections with Interlochen, where I taught for many years.

Hello Crispin,

Thank you. Yes I am still here but left the orchestra in 2010 to go back to school to write this story. I received my MFA in creative writing and now have a publisher for the new book. I’m still doing some teaching. Did we cross paths? I was an Interlochen student at 16! That’s a while ago.

all the best to you

Janet