Rachmaninoff’s Preludes have been a cornerstone of the piano repertoire, showcasing the composer’s wealth of emotions, propensity for lyricism and technical virtuosity. As part of HKU MUSE’s Russian Piano Classics series, Russian pianists Konstantin Lifschitz and Alexei Volodin took turns performing his Complete Preludes on two pianos. This ambitious undertaking stemmed from the artists’ long-standing friendship, dating back to their studies at the Gnessin Academy, where they would play for one another. During this concert, the two Steinways were positioned at an angle, adding an extra layer of intimacy to the performance, as if the audience was witnessing a conversation between two old friends.

Alexei Volodin & Konstantin Lifschitz, Rachmaninow 24 Préludes, Vienna Musikverein June 26th, 2020

Volodin opened the concert with Prelude Op. 3 No. 2 in C-sharp minor. While the pacing and voicing were judiciously executed at the beginning and towards the end, the middle section was somewhat marred by rushing and overpedalling.

Lifschitz performed Preludes No. 1, 3, 6, 8, 9 from Op. 23. Unfortunately, noticeable memory lapses in No. 1, 3 and 6, and technical imperfections, such as the uneven thirds and sixths in No. 9, undermined the performance. The phrasing sometimes appeared fragmented, the use of rubato contrived. Despite some lush moments with an intriguing emphasis on inner voices, his playing as a whole fell short of cogency.

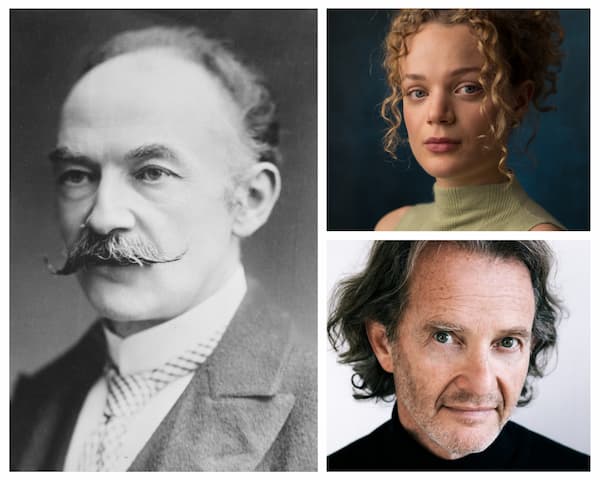

Konstantin Lifschitz and Alexei Volodin © HKU MUSE

By contrast, Volodin fared better in the other Preludes of Op. 23 with a hot-blooded take. Although his enthusiasm occasionally overwhelmed his control, Volodin’s interpretation was thoughtful, and lyricism always emerged whenever the music called for it, despite the overt virtuosity. For instance, his Prelude No. 2 in B-flat major displayed assertion and bravura, while No. 4 in D major and No. 10 in G-flat major were treated with sensitivity and poetry. However, his rushed Prelude No. 7 in C minor descended into a haze of sounds, obscuring the lines and harmonies, and more time could have been taken in the central section of No. 5 in G minor.

Nevertheless, the second half of the concert proved largely successful, especially Lifschitz’s performance. Volodin approached Preludes Op. 32 No. 1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12 similarly to Op. 23 – full of impetus and brilliance (e.g. No. 1, 3, 6), yet never at the expense of the music’s expressiveness. Notably, in Prelude No. 10 in B minor, Volodin created an effective build-up by a seemingly endless crescendo, eventually reaching the apogee of the entire Prelude.

© HKU MUSE

After intermission, Lifschitz played with much greater poise, focus and technical assurance. The underlying siciliano rhythm in Prelude No. 2 in B-flat minor provided a compelling tilting motion, while the burst of extreme violence in No. 4 in E minor yielded a state of exasperation. His feathery, subtle Prelude No. 5 in G major contrasted with the impressive dexterity in No. 8 in A minor. Prelude No. 13 in D-flat major was approached with suitable gravitas, conveying a sense of confronting adversity before ultimately triumphing over it and producing a truly magisterial effect. Interestingly, towards the end of this Prelude, Lifschitz seemed to be gesturing at Volodin to join him (as in the video above), but Volodin did not.

The setting of this concert highlights the differing approaches of the two pianists – Volodin’s approach was more conventional, straightforward and impassioned, while Lifschitz’s was rather unorthodox with more condensed ideas. Although I personally prefer a more measured approach to Rachmaninoff’s music that explores its expansive emotional landscape to an even greater extent, the pianists and the presenter should be commended for curating such a creative programme, especially given that this year marks the 150th anniversary of Rachmaninoff’s birth.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter