Cambridge Hall (later Camperdown Lodge), Newtown, Sydney

Eliza Emily Donnithorne (1821-1886) got engaged to George Cutherbertson, a clerk in a local shipping company in Sydney, Australia, or perhaps it was Stuart Donaldson, an aspiring politician in Sydney. Come the wedding day, the guests gather, the wedding breakfast is on the table, and the bride awaits in all her glory, but for nothing. George/Stuart, the cad, never turns up. Miss Donnithorne closed up her house and spent the next 30 years in isolation. It’s the humiliation of abandonment, and abandonment in front of her friends and relations, that drives her into madness.

In 1946, the story was given as

When the guests had departed, Eliza pulled down the blinds of her house, and for 30 years remained a hermit. The front door was chained permitting it to open only a few inches; callers never saw her, for when she was forced to speak to them, she remained out of sight. Here, for those long years, lived a woman in whom hope had died. When death at last came to Eliza, those who came to carry her to the greater peace of Camperdown Cemetery found her still clad in her bridal gown. Dust lay thick on the floor, and the window panes were thick with grime. And in the dining room, the wedding feast was uneaten, and the food had moldered into dust.

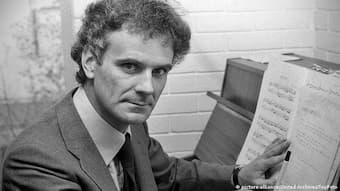

Peter Maxwell Davies

Sound familiar? Sound like Miss Havisham from Dickens’ Great Expectations? It is thought that Miss Donnithorne was the model for Miss Havisham, although later researchers aren’t certain if Miss Havisham’s story became pinned to that of Miss Donnithorne, but it’s a tragedy in any telling.

The story was taken up in 1974 by Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-2016) and set as Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot, an 8-part virtuoso piece for mezzo-soprano and small ensemble. Much like his earlier monodrama, Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969), it calls for extended vocal techniques, although, as Paul Griffiths notes, in this work, Miss Donnithorne ‘is generally more songful in her madness than George III.’ The text, by Australian writer and poet Randolph Stow, who also wrote the text for Eight Songs for a Mad King, turns the missing bridegroom into a naval officer so that naval references can be used in the text.

The work is set up with alternating pieces and dances:

Prelude

Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot

Recitative I

Her Dump

Nocturne

Her Rant

Recitative II

Her Reel

Randolph Stow

A ‘maggot’ means a favourite tune or, in a more old-fashioned sense, a whimsical or strange idea. A dump is a slow dance, a nocturne is not a dance but, literally, is music for night time, and a reel is a folk dance that requires at least 2 couples, if not more. For a woman alone in a house, a reel seems an ironic choice. On the other hand, given the story, it may mean to reel in a different sense.

In the Prelude, Miss Donnithorne invites the audience to her ‘imagined wedding,’ closing with the lines: ‘Miss Donnithorne begs the favour of your presence | at her nuptial feast and ball. | May it choke you one and all.’

Peter Maxwell Davies: Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot, Op. 60 – Prelude (Jane Manning, Miss Donnitorne; Psappha)

In the Maggot, she makes parallels between herself and the White Woman of Berners Street, a ghost seen on the streets of London.

Recitative I makes parallels between a famous Shakespearean character who drowned for love, Ophelia, and two famous Sydney street people, one a street-dweller who could recite all of Shakespeare by heart and the other a man who went around Sydney, writing ‘Eternity’ in chalk on the streets.

Her Dump makes a parallel between her wedding-cake tower and a lighthouse.

The Nocturne, in the middle, is for instruments alone.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot, Op. 60 – Nocturne (Psappha)

Her Rant has her seeing images in her wedding cake, confusing it with an attack on her body.

Recitative II is about the monster boys who yell outside her window, with such an appropriate language. But then….perhaps she should adopt one, who happens to look like her fiancé.

The work closes with Her Reel, where she hears her husband call from her chamber. She shifts in and out of reality – ‘Husband, I come’ and ‘Why am I sitting on the floor?’. Declaring her faithfulness, she pirouettes off to meet him, and so the work fades away, as does she.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot, Op. 60 – Her Reel (Psappha)

It’s a striking work, all the more so from being within her mind and perceptions. One writer on the work describes it as less a work of extended vocal technique than as a work for extended bel canto, moving the 19th century style into the 20th century. It’s painful and comedic, tragic and ludicrous, and pure Maxwell Davies.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter