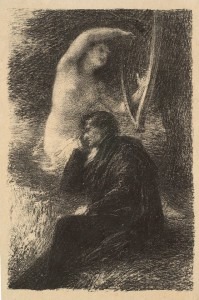

The ancients described the sound of the Aeolian harp as “music played without human hands.” As such, Romantic poets considered the instrument a source of natural and divine inspiration. Samuel Taylor Coleridge writes in his The Eolian Harp, of 1795:

And that simplest Lute,

Placed length-ways in the clasping casement, hark!

How by the desultory breeze caressed,

Like some coy maid half yielding to her lover,

It pours such sweet upbraiding, as must needs

Tempt to repeat the wrong! And now, its strings

Boldlier swept, the long sequacious notes

Over delicious surges sink and rise,

Such a soft floating witchery of sound

As twilight Elfins make, when they at eve

Voyage on gentle gales from Fairy-Land,

Where Melodies round honey-dropping flowers,

Footless and wild, like birds of Paradise,

Nor pause, nor perch, hovering on untamed wing!

O! the one Life within us and abroad,

Which meets all motion and becomes its soul,

A light in sound, a sound-like power in light,

Rhythm in all thought, and joyance everywhere—

Methinks, it should have been impossible

Not to love all things in a world so filled;

Where the breeze warbles, and the mute still air

Is Music slumbering on her instrument.

Percy Shelley followed in Coleridge’s footsteps, yet he considered the Aeolian harp an instrument of societal change. “There is a Power by which we are surrounded, like the atmosphere in which some motionless lyre is suspended, which visits with its breath our silent chords at will. Even the most imperial and stupendous qualities are nevertheless the passive slaves of some higher and more Omnipotent Power. This Power is God; and those who have been harmonized by their own will … give forth devinest melody, when the breath of universal being sweeps over their frame.”

Percy Shelley followed in Coleridge’s footsteps, yet he considered the Aeolian harp an instrument of societal change. “There is a Power by which we are surrounded, like the atmosphere in which some motionless lyre is suspended, which visits with its breath our silent chords at will. Even the most imperial and stupendous qualities are nevertheless the passive slaves of some higher and more Omnipotent Power. This Power is God; and those who have been harmonized by their own will … give forth devinest melody, when the breath of universal being sweeps over their frame.”

Frédéric Chopin: Étude Op. 25, No. 1

English poets saw the Aeolin harp as a source of inspiration and societal change. In German lands, the instrument gave listeners a longing for heaven and things beyond this world. And that is certainly what Robert Schumann heard when he saw Frédéric Chopin give a performance of the Étude Op. 25, No. 1 in A-flat major. “Let one imagine that an Aeolian harp had all the scales and that an artist’s hand had mingled them together in all kinds of fantastic decorations, but in such a way that you could always hear a deeper fundamental tone and a softly playing melody. He (Chopin) brought out distinctly every one of the little notes, but through the harmonies could be heard in sustained tones a wonderful melody…When the poem has ended you feel as you do after a blissful vision, seen in a dream, which, already half-awake, you would fain recall.” Calling it a poem rather than a study, the work quickly acquired the nickname “Aeolian harp.”

Sergei Lyapunov: 12 Etudes d’execution transcendante Op. 11, “No. 9 Aeolian Harp”

Henry Cowell: The Aeolian Harp

Towards the end of the 19th century Sergei Lyapunov followed suit and composed his “Aeolian Harp” Etude. So did Henry Cowell in 1923, as he created one of the first piano pieces to feature extended techniques on the piano that included plucking and sweeping of the pianist’s hands directly across the strings of the piano. Small-scale Aeolian harps are readily available for purchase, but if you wish to tackle Chopin, Lyapunov or Cowell, you will have to use your hands.