“Great teacher of musical truth”

Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomïzhsky

Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomïzhsky: “I am in love, my maiden, my beauty,”

“The fire of desire burns in my blood”

Glinka took his young charge under his compositional wing and instructed him in thoroughbass and counterpoint. They analyzed Beethoven symphonies and Mendelssohn overtures, and under the influence of rehearsals for his tutor’s A Life for the Tsar, Dargomïzhsky set his mind on writing a full-length opera. By 1841 he had completed the music for his first opera Esmeralda, but he failed to secure a performance at the Imperial Theatres. He made his living giving singing lessons, and in 1844 Dargomïzhsky traveled to Berlin, Brussels, Paris and Vienna and stayed for almost six months. Since absence makes the heart grow fonder, Dargomïzhsky found appreciation for the culture of his native land while spending time abroad. He wrote to a friend in May 1845, “There is no nation in the world better than the Russian, and, if the elements of poetry exist in Europe, they exist in Russia.” He quickly set to work on the imitation of characteristic melodic patterns of folk music and the intonation of Russian speech resulting in his opera Rusalka.

Glinka took his young charge under his compositional wing and instructed him in thoroughbass and counterpoint. They analyzed Beethoven symphonies and Mendelssohn overtures, and under the influence of rehearsals for his tutor’s A Life for the Tsar, Dargomïzhsky set his mind on writing a full-length opera. By 1841 he had completed the music for his first opera Esmeralda, but he failed to secure a performance at the Imperial Theatres. He made his living giving singing lessons, and in 1844 Dargomïzhsky traveled to Berlin, Brussels, Paris and Vienna and stayed for almost six months. Since absence makes the heart grow fonder, Dargomïzhsky found appreciation for the culture of his native land while spending time abroad. He wrote to a friend in May 1845, “There is no nation in the world better than the Russian, and, if the elements of poetry exist in Europe, they exist in Russia.” He quickly set to work on the imitation of characteristic melodic patterns of folk music and the intonation of Russian speech resulting in his opera Rusalka. Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomïzhsky: Rusalka, Act III “Some unknown power”

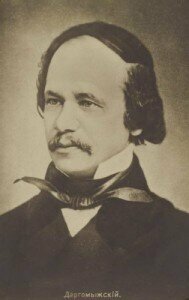

Photo of Aleksandr Dargomïzhsky

Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomïzhsky: Finnish Fantasy

In 1859, Dargomïzhsky was elected to the newly founded Russian Musical Society and formed an uneasy relationship with the group of young composers which had grown up around Balakirev. Unable to come to terms with the artistic aims of “The Five,” Dargomïzhsky visited Warsaw, Leipzig, Paris, and Brussels in 1864/65 and was cordially received by Liszt. Once he returned to Russia, he embarked on his most famous work, the opera The Stone Guest. The opera proved to be his swan song, as Dargomïzhsky died in January 1869 leaving the work incomplete. At his personal request, Cui wrote the Prelude and the end of the first scene, and Rimsky-Korsakov finished the orchestration by the end of 1870. “This strange work,” as the composer called it, met with a cool public reception. However, its pioneering employment of continuous melodic recitative supported by chordal accompaniment was seen by “The Five” as a “progressive approach to operatic expression.” Mussorgsky, for one, paid tribute to Dargomïzhsky in a pair of dedication exclaiming him the “great teacher of musical truth.”

Aleksandr Sergeyevich Dargomïzhsky: The Stone Guest, Act I: “Odelas tumanom Grenada”