Practice what you Preach

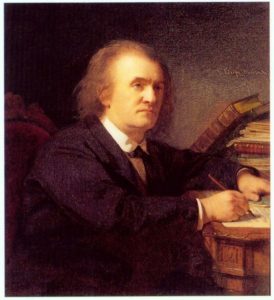

Portrait of Alexander Serov by Johann Köler

The Russian composer and critic Alexander Serov (1820-1871) never held an official position, he never taught a student, and he never belonged to any organized group or faction. Regardless, he was one of the most significant and most influential Russian musicians of the 1860s. He was known to the public as a music and culture critic long before making his mark as a composer. In fact, Serov became Russia’s leading authority in the field by writing important articles on a number of composers. As a fervent disciple of Wagner and the ideals of music drama, Serov championed the notion that much needed to be done in Russian music by encouraging the creation of indigenous repertoires. His most important essays are long-winded affairs infused with strong opinions on the ethics of dramatic music. His acerbic and high-spirited writing style assured that he did not enjoy cordial relationships with most other musicians or critics. Tchaikovsky brusquely observed that “Serov possessed very little creative originality, and that what drove him to start composing operas so late in life was not the inner impulse of a true creative artist, but rather his huge stock of musical knowledge acquired during his work as a critic.”

Alexander Serov: Judith (Irina Udalova, soprano; Elena Zaremba, mezzo-soprano; Mikhail Krutikov, bass; Nikolai Vassiliev, tenor; Anatolji Babykin, bass; Vladimir Krudiashov, tenor, Stanislav Suleimanov, bass; Peter Gluboky, bass; Maxim Mikhailov, bass; Irina Zhurina, contralto; Marina Shutova, mezzo-soprano; Lev Kuznetsov, tenor; Russian State Academy Chorus; Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra; Andrey Chistiakov, cond.)

Born in Saint Petersburg 200 years ago, Alexander Serov was destined for a career in civil service. His father had no sympathy for Alexander’s musical interest and by the age of 15 he was enrolled at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. He became friends with his classmate Vladimir Stasov, with whom he later had a spectacular falling out regarding the legacy of Mikhail Glinka. After graduating in 1840, he started working at the Ministry of Justice but continued to study music privately. Despite ambitious but abortive operatic projects, nothing more came of his musical efforts and in 1845 he was appointed president of the Court of Appeal in the Crimea. Serov wrote his first music criticism and resigned his post in 1848. Since his father refused to give him financial assistance, Serov had to return to his civil service post, but by 1851, he resigned for good. He made a slender living writing music criticism, but “a frenzied literary productivity made him an extraordinary reputation that virtually eclipsed his true musical vocation.”

Alexander Serov: Rogneda, “Prelude” (Grand Academic Choir of All-Union National Radio Service and Central Television Networks Russian Folk Instruments Orchestra; Vladimir Fedoseyev, cond.)

Serov met Wagner in Weimar in 1858, and upon his return to Russia proclaimed himself a disciple. This advocacy did his reputation more harm than good and he soon incurred the hostility of the “Mighty Handful,” and of his former school-friend Stasov. It all kicked off when Stasov published an obituary article on Glinka in which he questioned some aspects of A Life for the Tsar. Considering the work more of a “patriotic oratorio rather than a real opera,” Stasov declared Ruslan and Lyudmila, despite its dramaturgical shortcomings, the model of Russian national music. In Serov’s view, A Life for the Tsar perfectly satisfied the Wagnerian notions of an organically constructed music drama, and he summarily dismissed Ruslan. Attacks and counter-attacks fueled a bitter and protracted press war and Serov was portrayed as “blind and hostile to the New Russian School.” Nicknamed the “Russian Meyerbeer,” a “German Slavophile,” and an “agent of Wagner,” Serov suffered a torrent of abusive writing for decades after his death.

At the age of 40, Serov decided to put his theoretical and critical knowledge into practice by writing an opera himself. He settled on the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes, and the work was quickly rejected by the “Mighty Handful,” and by Wagner himself. Tchaikovsky on the other hand, “loved Judith and he fell in love with it at once and with a loyalty that lasted all his life.” Similarly, the public received Judith enthusiastically, and the subject of Serov’s next opera was the legendary world of pagan Russia. Rogneda proved to be even more successful than Judith, and it received about 70 performances between 1865 and 1870. Serov was offered a post at the Moscow Conservatory in 1865, put calling it an “exile in a rather provincial second city of Russia,” turned down the offer. The post was eventually handed to the young Tchaikovsky. Serov’s last opera, The Power of the Fiend is an ambitious and original work, and scholars have called it his “finest achievement for its integration of Russian everyday life with music drama in a canvas of unprecedented realism. Serov died of a heart attack before he could finish the orchestration, and his wife Valentina and the composer Nikolay Solovyev completed the score. Although his operas have not survived in the repertory, Serov was the most significant Russian composer between Dargomyzhsky’s Rusalka and the works of Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, and Tchaikovsky.

Alexander Serov: The Power of the Fiend, (excerpts) (Veronica Borisenko, mezzo-soprano; Elizaveta Antonova, alto; Aleksey Petrovich Ivanov, bass; Nikolay Schegolkov, baritone; Alexander Vedernikov I, vocals; Bolshoi Theatre Chorus; Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra; Kirill Kondrashin, cond.)