The story is brief and mysterious. A father on an urgent mission, riding through the night with his ailing child in his arms to get help. We open in medias res; the piano tells us before the words enter that the horse is galloping, the mission is urgent. As they gallop along, the child is restless and talks to his father, describing the actions of the Erl King. The father hushes him, explaining it as a natural phenomenon: a streak of mist, the sound of the wind in dried leaves, a willow tree. The child grows increasingly hysterical, closing with a cry that the Erl King is hurting him. The father draws him closer and rides on more desperately. When he finally reaches his goal, the child is dead in his arms. The last two words are ‘war tot’ (was dead).

Mortiz von Schwind: Erlkönig, 1849 (Prague: National Gallery)

In his painting, done in 1849, Moritz von Schwind captures the horrors conjured up in the imagination of the child and how a windy night can turn the forest into a place full of danger.

It’s worthwhile to read the poem so you understand the action in the poem and the settings.

| Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind? Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind; Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm, Er faßt ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm. | Who rides so late through night and wind? It is the father with his child. He has the boy firmly in his arms, He holds him safely, he keeps him warm. |

| Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht? Siehst, Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht? Den Erlenkönig mit Kron’ und Schweif? Mein Sohn, es ist ein Nebelstreif. | My son, why do you hide your face so fearfully? Father, don’t you see the Erl-King? The Erl-King with crown and tail? My son, it is a streak of mist. |

| “Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir! Gar schöne Spiele spiel’ ich mit dir; Manch’ bunte Blumen sind an dem Strand, Meine Mutter hat manch gülden Gewand.” | “You dear child, go with me! I will play very beautiful games with you; Many colourful flowers are on the shore, My mother has many golden robes.” |

| Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht, Was Erlenkönig mir leise verspricht? Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind; In dürren Blättern säuselt der Wind. | My father, my father, and do you not hear What the Erl-King softly promises me? Be calm, stay calm, my child; Through dry leaves, the wind is rustling. |

| “Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn? Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön; Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn, Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.” | “Will you, fine boy, come with me? My daughters shall wait on you beautifully; My daughters lead the nightly dance, And rock and dance and sing you to sleep.” |

| Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort Erlkönigs Töchter am düstern Ort? Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich seh’ es genau: Es scheinen die alten Weiden so grau. | My father, my father, and don’t you see there The Erl-King’s daughters in the gloomy place? My son, my son, I see it clearly: There shimmer the old willows so grey. |

| “Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt; Und bist du nicht willig, so brauch’ ich Gewalt.” Mein Vater, mein Vater, jetzt faßt er mich an! Erlkönig hat mir ein Leids getan! | “I love you, your beautiful form excites me; And if you’re not willing, then I will use force.” My father, my father, he’s grabbing me now! The Erl-King has done me harm! |

| Dem Vater grauset’s; er reitet geschwind, Er hält in den Armen das ächzende Kind, Erreicht den Hof mit Mühe und Not; In seinen Armen, das Kind war tot. | The father is horrified; he swiftly rides on, He holds the moaning child in his arms, Reaches the farm with great difficulty; In his arms, the child was dead. |

The poem was written in 1782 by Johann von Goethe and was set to music by over 100 composers. The only setting that has remained popular since its composition over 200 years ago is Franz Schubert’s dramatic setting from 1815.

The poem requires the singer to imitate 4 people: the narrator, the high voice of the child, the low voice of his father, and the persuasive voice (sweet turning to cruel) of the Erl King.

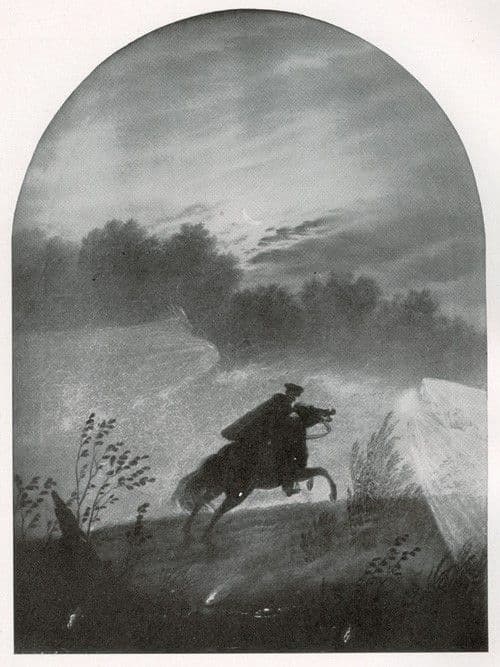

Carl Gustav Carus (1789–1869): Der Erlkönig (Kunsthalle Hamburg)

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (Matthias Goerne, baritone; Andreas Haefliger, piano)

Much as we love Schubert’s, Goethe was not a fan when it was sent to him in 1815; when he heard a live performance in 1830, though, he is said to have commented: ‘I have heard this composition once before, when it did not appeal to me at all; but sung in this way the whole shapes itself into a visible picture’. It may be that he thought Schubert’s setting too dramatic and that the music overpowered the poetry, but when he heard it in performance, the equality of the two parts equalled out.

But, what if you don’t have a phenomenal accompanist on call and you’re not a singer? Is this work closed to you? Of course not. The song has been arranged for other performing forces by Franz Liszt (1838 and 1876 for piano; 1860 for solo voice and orchestra), by Wilhelm Ernst (1854 for violin solo), by Hector Berlioz (1860 for solo voice and orchestra), and as late as 1914 by Max Reger for solo voice and orchestra, and by many others.

Liszt uses the entirety of the piano, plus its ability to play both loudly and softly, to great advantage in his setting. This is a virtuosic piano transcription, starting from an already difficult original.

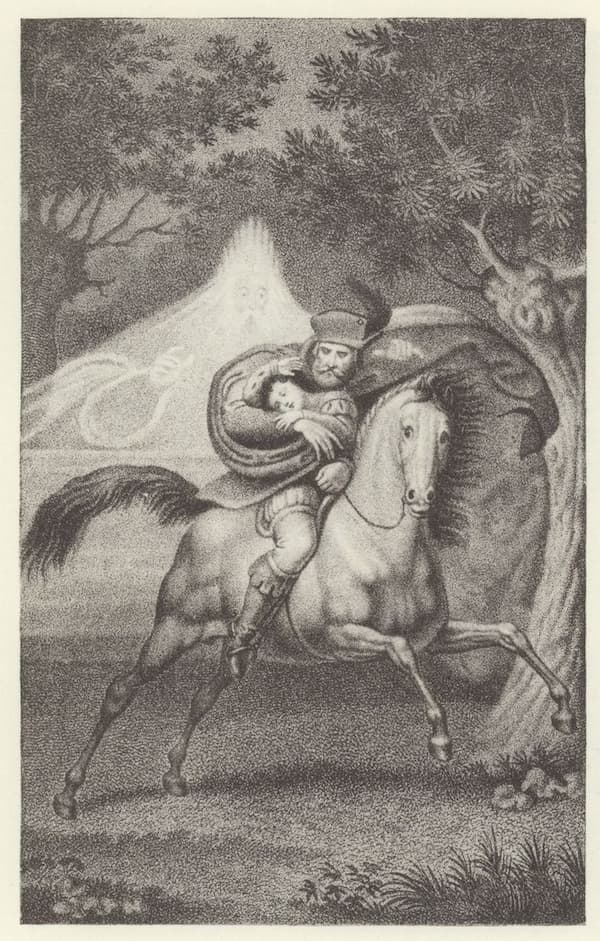

Ludwig Ferdinand Schnorr von Carolsfeld: Der Erlkönig, ca 1830–1835 (Munich; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen)

Franz Liszt: 12 Lieder von Schubert, S558/R243 – No. 4. Erlkönig (Murray Perahia, piano)

When Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst made his transcription in 1854, it was considered an apex of violin technique. In a single instrument, on only 4 strings, the violinist creates the 4 characters and plays the piano accompaniment at the same time. Ernst’s requirements for performance stretched the performer because he required double, triple, and even quadruple stops (play 2, 3 or 4 notes at once). To present the playing requirement most clearly, parts of the score are written on two staves. In this example, the second stave carries the Erlkönig’s voice, which the violinist is instructed to play the voice with harmonics, while, at the same time, continuing to play the piano/horse part. The speed is a quick Presto, and the difficulty is immense.

Score detail from Ernst: Le roi des aulnes, Op. 26 (Vienna: Cranz, ca 1854)

Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst: Le roi des aulnes, Op. 26 (after Schubert’s Erlkönig) (Gidon Kremer, violin)

Hugo Ulrich (1827–1872) started his career as a talented young composer, but ill-health soon removed him from his teaching career at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin. Confined to his house, he made his living in creating ‘practical home editions’ of larger works, including a set of complete symphonies and quartets by Haydn and Mozart, for piano, both 2-hand and 4-hand. One of those was Schubert’s Erlkönig. It’s nice to hear this duo version taken at a slower tempo.

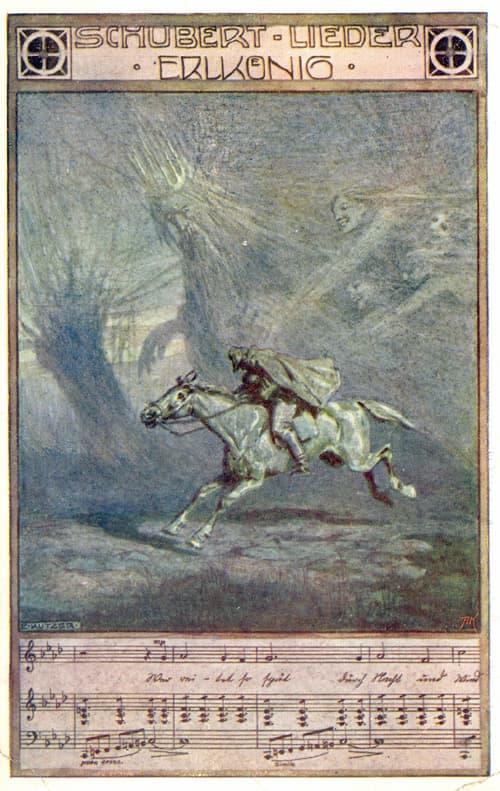

Ernst Kutzer: Der Erlkönig with Schubert score

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, D. 328 (arr. H. Ulrich for piano 4 hands) (Palmas Piano Duo)

An unusual and very modern-sounding arrangement is that for piano and drum set. The piano, of course, is tuned. The percussion isn’t pitched. Side drums, cymbals, and all kinds of percussion come into play, giving the piano part a bit more splash than might be expected.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, D. 328 (arr. Akira Horikoshi and Yuko Mifune for piano and drums) (Obsession)

In this arrangement by C.G. Wolff for violin and viola, he uses the two distinct voices of the instruments to better convey the voices of the four protagonists.

Yuliy Yulevich Klever: Der Erlkönig

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. C.G. Wolff for violin and viola) (Alena Baeva, violin; Yuri Bashmet, viola)

When reduced for viola and piano, the piano can take the piano part, and then the viola takes on the four characters. Schubert’s writing, with the high voice of the child, the low voice of the reassuring father, and the wheedling of the Erlkönig, all come through beautifully.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. for viola and piano) (Sachiko Suda, viola; Nozomi Matsumoto, piano)

When arranged for string quartet, the poor lower voices are left to gallop along at the beginning, but are soon able to make their own supporting voices. The wide pitch range available in a string quartet means that the violin can be the child and the Erlkönig, and the warmer viola can be the father.

Gustav Heinrich Naeke: Erlkönig 1827

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. for string quartet) (Goldmund Quartet)

When expanded to a string orchestra (i.e., no winds, brass, or percussion), the effect of the story is less immediate. The individuality of the voices gets lost.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. for string orchestra) (Metamorphose String Orchestra; Pavel Lyubomudrov, cond.)

Guitarist and arranger Johan Smith has made many arrangements of classical for guitar, significantly expanding the guitar repertoire. His arrangement of Erlkönig uses the singing qualities of the guitar to convey the Erlking’s blandishments, the middle pitches for the child’s speech, a more calming sound for the father’s voice. As the situation becomes more desperate, Smith skillfully starts overlapping lines until the fatal ending.

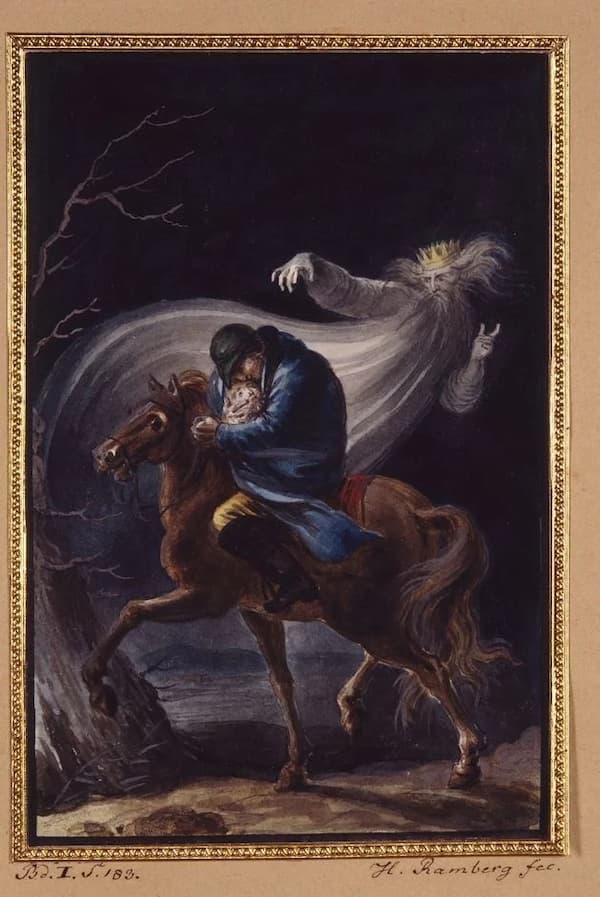

Johann Heinrich Ramberg: Erlkönig (Klassik Stiftung Weimar)

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. J. Smith for guitar) (Johan Smith, guitar)

Now that we’ve explored the instrumental arrangements and transcriptions. Let’s go back to the vocal side. An arrangement in 1860 was by Hector Berlioz, who applied all of his mastery of orchestration to develop a truly dark world. The orchestra is more than just the horse. Berlioz is able to create the mists and trees of the world the father describes, and, even more magically, the promises that the Erl King makes.

Carl Gottlieb Peschel: Der Erlkönig, fresco, 1838 (Belvedere Schön Höhe)

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. H. Berlioz for voice and orchestra) (Anne Sofie von Otter, Mezzo-soprano; Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. H. Berlioz for voice and orchestra) (Mary Bevan, soprano; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Edward Gardner, cond.)

Franz Liszt also did a voice and orchestra arrangement in 1860. The horns at the beginning tell you immediately that Liszt did more than just an orchestral transcription!

Franz Liszt: 6 Lieder von Schubert, S375/R651 (version for voice and orchestra) – No. 4. Erlkönig (Thomas Hampson, baritone; Vienna Academy Orchestra; Martin Haselböck, conductor)

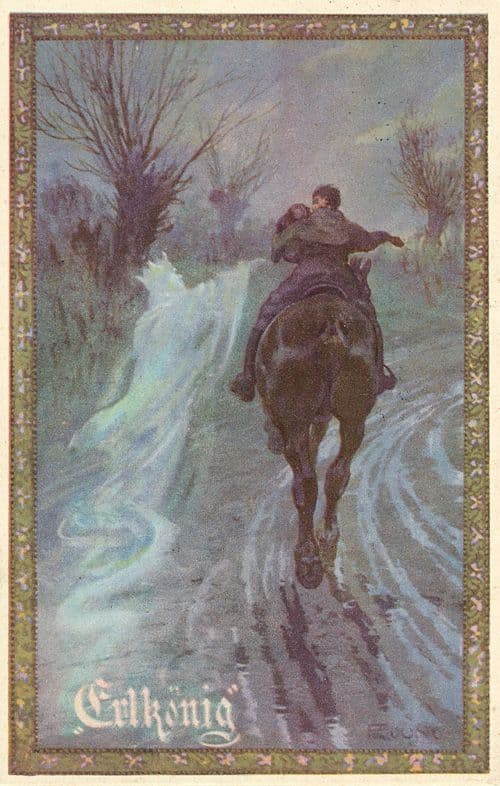

F. Jung: Erlkönig, 1920, postcard

German composer Max Reger made his transcription for voice and in 1914. He’s benefited from both the Berlioz and Liszt transcriptions that preceded his.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. M. Reger for voice and orchestra) (Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Verbier Festival Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)

Korean composer Sungmin Ahn has done an arrangement, as has Alexander Schmalcz. Schmalcz’s arrangement has some unique elements, particularly in pairing the instruments of the orchestra, where ‘there are stretches during which only the timpani and double bass are heard, creating an “extremely strange, deep, dull and gruff murmur”’.

Mortiz von Schwind: Der Erlkönig, ca 1830 (Vienna: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere)

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. A. Schmalcz for voice and orchestra) (Matthias Goerne, baritone; Bremen Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie)

In arranging the song for choir, Hideki Chihara felt it necessary to start it off with the crack of a whip. Instead of joining the father and child somewhere on their journey, we are with them from the beginning to the end. The choir is the horse and the characters, sometimes switching in mid-stream from character to horse in a phrase.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. Hideki Chihara for choir) (Taro Singers; Hiroshi Satoi, cond.)

When the choir is the Vienna Boys Choir, we have a very different experience. As arranged by Oliver Gies, the lack of low voices makes for a very different musical experience. The emphasis on the supernatural comes to the fore, and the supporting line of the horse/piano is changed for something much more rhythmically modern. The extended ending doesn’t really make it more effective than just ‘war tot’.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, Op. 1, D. 328 (arr. O. Gies for choir) (Vienna Boys Choir; Manolo Cagnin, cond.)

The arrangement by David Jacques for voice and guitar is particularly interesting when that voice is countertenor Philippe Jaroussky.

Franz Schubert: Erlkönig, D. 328 (arr. D. Jacques for voice and guitar) (Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor; Thibaut Garcia, guitar)

Or, you could just read the poem (with the appropriate comedy stance!)

Marco Rima: Der Erlkönig

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter