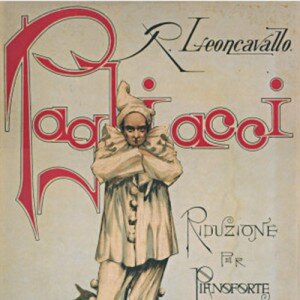

A fair number of composers are primarily known for only one piece of music. And such is certainly the case with the Italian opera composer and librettist Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919). His single lasting contribution, Pagliacci (Clowns), is still one of the most popular works in the repertoire, and the most famous aria “Vesti la giubba” later recorded by Enrico Caruso was the first recording to sell one million copies. For Caruso, Pagliacci had personal relevance, as his partner Ada Giachetti—who bore him two children—ran off with his chauffeur. The fabled tenor once wrote that whenever he sang the role of “Canio” in Pagliacci, he wept genuine tears thinking of his own unfaithful lover. Be that as it may, Leoncavallo’s path to success was a difficult one, as his first operatic efforts were disasters. The production of his student work, Chatterton, came to naught as the impresario ran off with the money Leoncavallo had provided to cover the costs.

A fair number of composers are primarily known for only one piece of music. And such is certainly the case with the Italian opera composer and librettist Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919). His single lasting contribution, Pagliacci (Clowns), is still one of the most popular works in the repertoire, and the most famous aria “Vesti la giubba” later recorded by Enrico Caruso was the first recording to sell one million copies. For Caruso, Pagliacci had personal relevance, as his partner Ada Giachetti—who bore him two children—ran off with his chauffeur. The fabled tenor once wrote that whenever he sang the role of “Canio” in Pagliacci, he wept genuine tears thinking of his own unfaithful lover. Be that as it may, Leoncavallo’s path to success was a difficult one, as his first operatic efforts were disasters. The production of his student work, Chatterton, came to naught as the impresario ran off with the money Leoncavallo had provided to cover the costs.

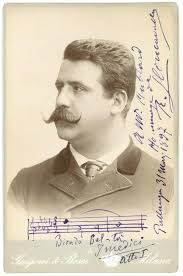

Ruggero Leoncavallo

Previously, Leoncavallo had spent three years in Egypt, working as a piano teacher and pianist to the brother of the new Khedive Tewfik Pasha. Sadly, the 1882 revolts in Alexandria and Cairo forced his return to Europe, and for some time he worked as a café pianist in Montmartre. And although he managed to sign up with the influential publisher Giulio Ricordi, irreconcilable creative differences quickly emerged. Desperate for success, Leoncavallo witnessed the sensational success of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana in 1890. This one-act melodrama highlights the passions of Sicilian peasants, and in true verismo style blends religiosity and sexuality in a lyrical tour de force. Leoncavallo was determined to try his hand at a similar work. In a flash of insight he conflated a play involving the fatal jealousies in a traveling troupe of actors, with a middle-age actor murdering his unfaithful actress wife onstage during a performance, with a real-life story encountered by his father, a police magistrate in Naples.

Enrico Caruso as Canio

Leoncavallo might have embellished on the story, but there was indeed a murderous incident during his childhood. In 1865, Gaetano D’Alessandro and his brother Luigi murdered the Leoncavallo family servant Gaetano Scavello. The brutal murder was the result of a series of perceived romantic entanglements involving Scavello, Luigi, D’Alessandro and a village girl with whom they were all infatuated. And Leoncavallo’s father was indeed the presiding magistrate over the criminal investigation. But there are more twists in this sordid story. Once Leoncavallo’s libretto had been published in the 1894 French translation, the French author Catulle Mendès asserted that it resembled his 1887 play La Femme de Tabarin, a play-within-a-play with a clown murdering his wife. Mendès sued Leoncavallo, who pleaded ignorance, but when Mendès himself got accused of plagiarism, he dropped the lawsuit.

Ruggero Leoncavallo: “Vesti la giubba” (Beniamino Gigli)

Ruggero Leoncavallo: “Vesti la giubba” (Beniamino Gigli)

In the end, Leoncavall’s opera features five characters derived from the Italian tradition of commedia dell’arte. We find the stock characters of the sad clown, the stunning beauty, the dashing young lover, with the addition of a hunchback actor and the villager. This troupe of traveling actors arrive in the southern Italian city of Calabria on 15 August, a holy day in the Catholic calendar celebrating the Assumption of Mary into heaven. Before the curtain rises, “Tonio” announces that the story is about real people. “Canio” is to perform that evening, and it is suggested that Tonio would like to make love to Canio’s wife “Nedda.” Tonio tries in vain to kiss Nedda, and in revenge, Tonio fetches Canio while Nedda is talking to her real lover, the villager Silvio. As the play begins, Canio re-lives on stage the situation that exists in real life. In the end, he stabs his wife, who refuses to name her lover, and when Silvio tries to help her, he is also killed. The horrified audience then hears the celebrated final line: “The comedy is finished!” This story line is unfortunately just as realistic and relevant today as it was in 1892, as it highlights violence against women by jealous and abusive husbands. There is no comedy here, just another dark chapter in the category of Art imitating Life.