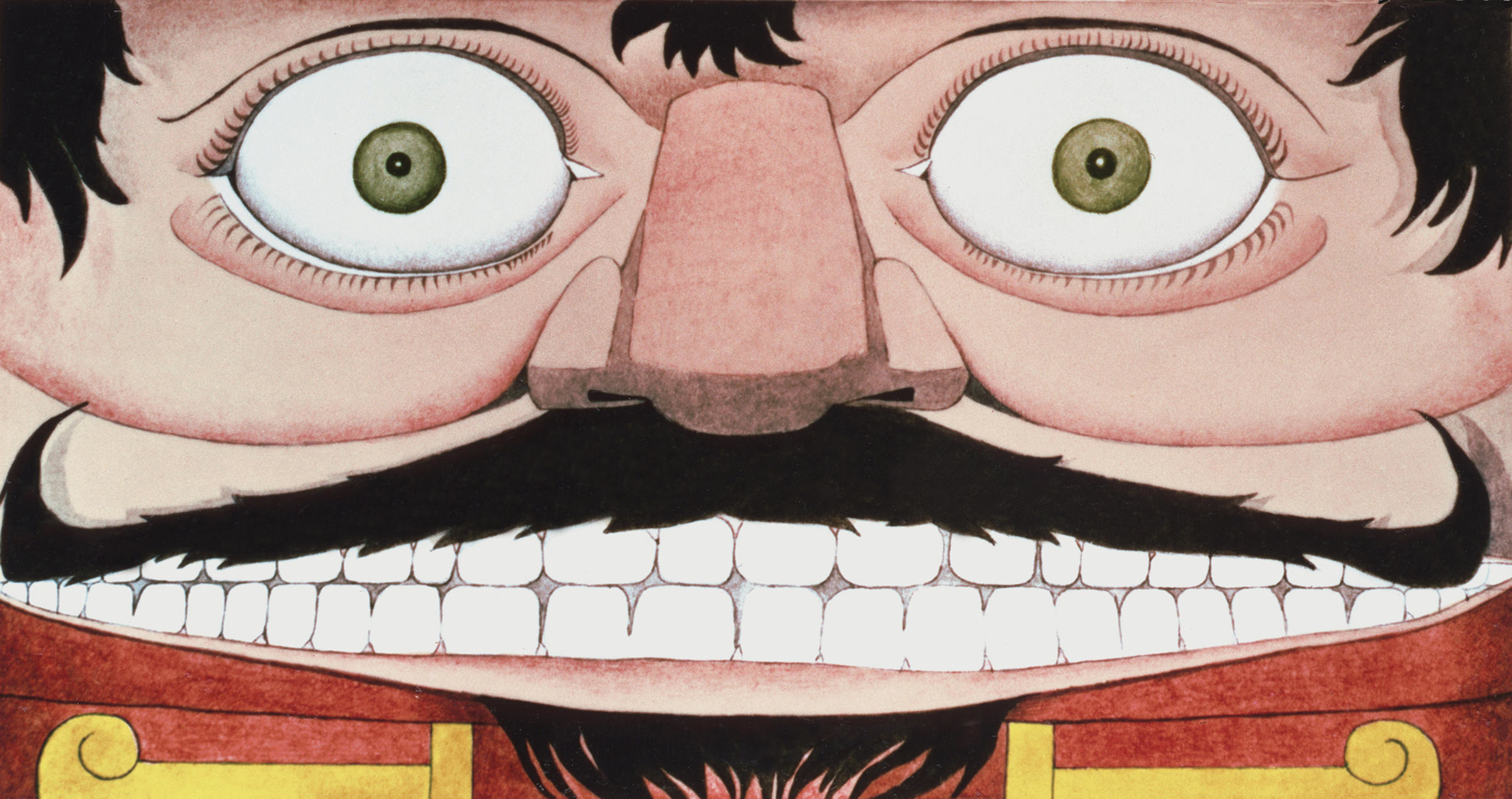

Bedlam from The Rake’s Progress – Glyndebourne Opera

In earlier articles we’ve looked at how art has inspired music. Now, we’re taking a look at the artists working within music. The English artist David Hockney (b. 1937) works in many different media as a painter, a draughtsman, printmaker, photographer, and stage designer. Considered one of most influential British artists of the 20th century, he has been designing opera sets for over 40 years. He started by designing the backdrops, props, and stage curtains for Glyndebourne Opera in 1975.

The Appearance of The Queen Of The Night From The Magic Flute

He also did designs for The Magic Flute at Glyndebourne, making a visual representation of the chaos of The Queen of Night’s world versus the order of Sarastro’s.

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte: Act I: Rezitativ und Arie: O zitt’re nicht, mein lieber Sohn! (Beverly Hoch, Queen of Night; London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

An Avenue of Palms From The Magic Flute

The Met commissioned him to do set designs and costumes for three rarely performed 20th-century French works: Satie’s Parade, Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias, and Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges. With these designs, he was competing with the radical cutting edge of 20th century design: Parade’s original designer was Pablo Picasso and Les mamelles de Tirésias had its premiere at the Opéra-Comique with costumes and décor by Erté. Hockney met this challenge by making reference to the earlier productions. As the New York Times reviewer John Russell noted, it was “…the Parade of 1917 revisited as if in a dream, with Picasso very much in mind, both as the original designer and as the poet of Les Saltimbanques – the tumblers and harlequins who turn up over and over again in the work of Picasso’s Rose period.”

Hockney: Harlequin Against Gold

Picasso: Harlequin (1917 (Art Institute of Chicago)

For Les mamelles de Tirésias, Hockney used as his inspiration the gowns that Erté had used in the original 1947 Opéra-Comique production, which were the same as the ones he had designed for the fashion house Paul Poiret’s.

Hockney: Poiret Gowns for Les mamelles de Tirésias

Image from a 1908 Poiret catalogue

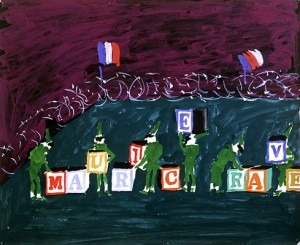

For L’enfant et les sortilèges and its story of the bad boy who learns to be good, the production opened with Picasso’s harlequins giving us the name of the new composer.

Punchinellos Changing Blocks

The set is on permanent exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art – Spalding House branch.

Hockney: The Garden

Other stage designs include a 1987 Tristan und Isolde for the L.A. Music Center Opera, a 1992 Frau ohne Schatten for the Royal Opera House in London, and a 1992 Turandot for a joint production of Chicago’s Lyric opera and the San Francisco Opera, that avoids the largely gold-colored designs that appear on most opera stages for an overblown and brilliant crimson.

Hockney: Turandot

When an artist designs for the stage, we can look at the work at more than the surface level. In this case, Hockney brings a depth of knowledge of the art used for earlier production and his own sensibility as an artist and designer into play. We see Erté via Hockney, we see Picasso via Hockney, and in all cases, we see Hockney.

All Hockney images are from his website.