Just when we thought that the virus news from China could not get much worse, comes a report from Wuhan province that a deadly strain of Bird flu has been detected on the southern border of Hubei province. The good news is that at this point no human cases have been reported; the bad news is that avian influenza viruses in humans are highly pathogenic and frequently lethal. These potent viruses occur naturally among wild aquatic birds, but they usually don’t get sick. Since the viruses are highly contagious among birds, they can infect domestic poultry like chickens and ducks. And that’s when it can get portentous. Some viruses can cause severe disease in domestic poultry with a mortality rate close to 100%. Usually, these viruses do not infect people, but human infections have been known. When this happens, it leads to some of the most serious illnesses and a mortality rate of 60%. Frequently, at the center of avian influenza outbreaks, like the current one in Hubei, stands the humble chicken. Given how close humans and chickens live together in rural communities, it really is only a question of time before we will have to deal with a pandemic threat. You might rightly have guessed that the humble chicken turns up frequently in literature and music, but it rarely takes on a threatening or menacing demeanor.

Just when we thought that the virus news from China could not get much worse, comes a report from Wuhan province that a deadly strain of Bird flu has been detected on the southern border of Hubei province. The good news is that at this point no human cases have been reported; the bad news is that avian influenza viruses in humans are highly pathogenic and frequently lethal. These potent viruses occur naturally among wild aquatic birds, but they usually don’t get sick. Since the viruses are highly contagious among birds, they can infect domestic poultry like chickens and ducks. And that’s when it can get portentous. Some viruses can cause severe disease in domestic poultry with a mortality rate close to 100%. Usually, these viruses do not infect people, but human infections have been known. When this happens, it leads to some of the most serious illnesses and a mortality rate of 60%. Frequently, at the center of avian influenza outbreaks, like the current one in Hubei, stands the humble chicken. Given how close humans and chickens live together in rural communities, it really is only a question of time before we will have to deal with a pandemic threat. You might rightly have guessed that the humble chicken turns up frequently in literature and music, but it rarely takes on a threatening or menacing demeanor.

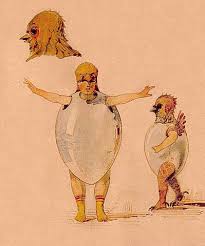

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (orch. Ravel) “Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Giuseppe Sinopoli, cond.)

Sketches of theatre costumes for the ballet Trilby

Chickens are some of the most common and widespread domestic animals with population worldwide counted in billions. The domesticated fowl probably originated on the Indian subcontinent and made its way to Asia Minor before arriving in Greece by the 5th century. Originally it seems, chickens were raised for cockfighting and other special ceremonies, but they entered the food chain during the Hellenistic period, sometimes between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC. Known as the bird that gives birth every day, chickens are still sacred animals in some culture, and in the New Testament the rooster is a symbol of vigilance and betrayal. In traditional Jewish practice, the animal is swung around the head and then slaughtered on the afternoon before Yom Kippur, and in a good many Central European folk tales, the devil flees at the first crowing of a rooster. Nothing that sinister in Martinů’s Three Songs for Christmastime composed in 1929. In fact, the composer sets Thierry de Gramont’s verse about a recalcitrant fowl in engagingly childlike terms.

Bohuslav Martinů: 3 Christmas Songs, H. 184b “Le poulet” (Olga Cerna, mezzo-soprano; Jitka Čechová, piano)

Predictably, the chicken also made it into popular culture ranging from the “Chicken Dance” to a number of poultry related folk tunes. Probably the best know dance tune is called “Chicken Reel,” and it was originally composed and published in 1910. Lyrics were added only a couple months later, it has since passed into modern folk tradition.

Predictably, the chicken also made it into popular culture ranging from the “Chicken Dance” to a number of poultry related folk tunes. Probably the best know dance tune is called “Chicken Reel,” and it was originally composed and published in 1910. Lyrics were added only a couple months later, it has since passed into modern folk tradition.

Way down in Carolina where the sweet potatoes grow

There lives a dusky maiden by the name of Liza Snow

She used to go to parties where they’d always make her sing,

But say you ought to see that Baby do the pigeon wing.

They held a dancing contest and were goin’ to give a prize

They all had on their finest and it now was up to Lize.

Just who was goin’ to win it ev’rybody there could feel,

When Liza hollered to the band to play the Chicken Reel

Clear the crowd away

Tell the band to play

When you hear me say “GO” My honey

Oh, you Chicken Reel, how you make me feel

Say it’s really so entrancin’

Who could really keep from dancin’,

That’s the music sweet, like the chicken meat

Give it to me with the dressin’

I don’t need no dancin’ lesson

Put all the other fine selections right away

That is the only tune I want to hear you play

When I get married if there’s music I will say

“Hey boss keep a-playin’ Chicken Reel all day”

Leroy Anderson: Chicken Reel (BBC Concert Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Golden Cockerel

The great Russian author Alexander Pushkin penned colorful tales of supernatural magic with decidedly down to earth morals. The fairy tale of the “Golden Cockerel” appeared in 1834 and served Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as the inspiration for an opera presenting a caricature of the precarious political situation in Russia. The opera opens with a mysterious Astrologer appearing before the curtain in the prologue and announcing to the audience that they are going to see and hear a fictional tale from long ago. It is the story of the inept Tsar Dodon who believes that his country is in danger from a neighboring country ruled by a beautiful Tsaritsa. The Astrologer presents him with a magical Golden Cockerel, who is able to see into the future. When the cockerel confirms that the Tsaritsa does intend to take over his country, Dodon sends his army into battle. The Golden Cockerel makes sure that the Tsar falls hopelessly in love with the beautiful Tsarina. The Tsaritsa plays along and performs a seductive dance, inviting the Tsar to consummate the relationship but he is just too clumsy. She engineers a marriage proposal from Dodon, and with the wedding festivities in full swing, the Astrologer reappears and reminds the Tsar that he has granted him a wish. But when the Astrologer demands the Tsarina, Dodon kills him with a vicious blow. Loyal to his master, the Golden Cockerel pecks through the Tsar’s jugular.