Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

In most performances of The Nutcracker, the orchestra is buried in the pit so you don’t really have a chance to see them performing. One element that came out beautifully was the counterpoint, the supporting musical lines in the other voices.

Listen, for example, in ‘The Decoration of the Christmas Tree.’ We start with the descending line in the violins, but listen to what the woodwinds are doing behind their sound. Then, when the woodwinds take the melody, the violins provide a countermelody. It is this intertwining of voices that makes The Nutcracker so interesting as a musical work, beyond its role supporting dancers.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, Op. 71: Act I, Tableau 1: Decoration of the Christmas tree (Russian National Orchestra; Mikhail Pletnev, cond.)

In the following ‘March,’ we have the fanfares in the trumpets and at the same time, the violins are playing against the woodwinds to broaden the relative narrowness of the fanfare.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, Op. 71: Act I, Tableau 1: March (Russian National Orchestra; Mikhail Pletnev, cond.)

In the second act, where young Clara and the Nutcracker (now a prince) are in the Kingdom of Sweets, there follows a set of divertissements: A Spanish Dance for Chocolate, An Arabian Dance for Coffee, and a Chinese Dance for Tea. Counterpoint has a part to play here, too.

Listen in the Spanish Dance where the melody is in the violins, but the woodwinds are making little comments behind (00:37) while the maracas beat out their own rhythm. It’s this combination of melody, rhythm, and countermelody that makes this work live.

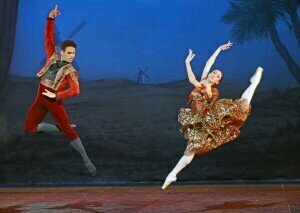

Spanish Dance with Yonah Acosta, Anjuli Hudson

(English National Ballet, 2014)

The Chinese Dance, for flute, contrasts the rocking bassoon with the high flute. The plucking on the strings gradually gets more complex and the whole section rocks to the end.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, Op. 71: Act II Tableau 3: Divertissement: c. Tea – Chinese Dance (Russian National Orchestra; Mikhail Pletnev, cond.)

The solo dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy was a chance for Tchaikovsky to write for a new instrument he’d just discovered in France, the celeste (‘heavenly sound’). The sweet, ethereal sound of the instrument was the perfect accompaniment to the heavenly vision on stage. But listen behind that sound to what the bassoon and the clarinet add. Later, hear what the violins add.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, Op. 71: Act II Tableau 3: Variation 2: Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy (Russian National Orchestra; Mikhail Pletnev, cond.)

Listen to your favourite ballet without the visual ballet – there’s a lot of great music going on!