Credit: http://www.classicfm.com/

Once he set back to work in 1815, Beethoven miraculously issued a group of relentlessly obsessive masterpieces. This veritable paradigm shift in musical conception prompted scholars to suggest “we must look almost a century ahead, to Debussy and Schoenberg, in order to find so radical a transformation of musical thought.” Building tension between the progressive and the retrospective, Beethoven intentionally blurs the lines of division between phrases, with cadences constantly changing position within the measure.

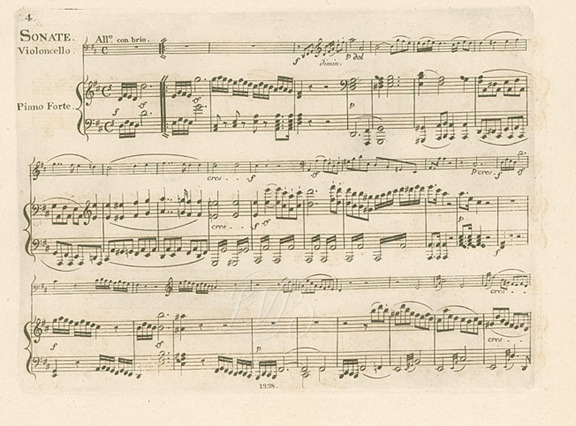

These kinds of improvisatory techniques, together with a completely unique and concentrated assessment of counterpoint, suddenly become part of the creative process. We can rightfully suggest that these compositional hallmarks of Beethoven’s late style first emerge in the two cello sonatas Op. 102. Originally, hoping to publish the two sonatas in an English edition, Beethoven had dedicated the pair to the visiting English pianist and cellist Charles Neate. In the end, however, the works are dedicated to Countess Maria von Erdödy, a long-time patron of Beethoven and a good amateur pianist.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 5, Op. 102, No. 2

Exuding a sense of transcendent spirituality, Op. 102 No. 2 is a concentrated and relentless bundle of energy. Each musical gesture is kept to the bare essentials, and each note occupies an important place in the overall structure. Traversing the same terrain as his last string quartets, Beethoven opens with a typically terse gesture in the piano, that is later taken up by the cello. This gesture, essentially a cadential closing figure, is extensively used in the development and as the transitional material to a more lyrical second subject. A movement of “robust and resolute grandeur” according to Carl Czerny, its fluid structure is punctuated by unexpected harmonic digressions and a highly modified recapitulation. In the substantial central movement, Beethoven allows the cello to display its lyrical potential. The opening chorale in the minor key bookends a serene central section in the major key, and an otherworldly coda immerses us into a remote and ethereal musical landscape. Emerging hesitantly, the last movement eventually launches an almost abstract fugal subject. Looking ahead to the relentless counterpoint of the Hammerklavier and the Grosse Fuge, Beethoven is striving to rejuvenate the function and expressive possibilities of counterpoint. Concordantly, he is uncompromisingly exploring the extreme range of the newly developing keyboard instrument. The unexpected return of the first-movement’s themes in the finale function in the sense of a reminiscence rather than as a formalist recapitulation. Beethoven’s contemporaries did not understand the composer’s mature compositional style or his late compositions. Yet the revolutionary element, the free, impulsive, mysterious, demonic spirit and the underlying conception of music as a mode of self-expression, fascinated an entire Romantic generation.

The Cello Sonata No. 5, Op. 102, No. 2 will be performed by Zuill Bailey & John York at the Wimbledon International Music Festival on 22 November 2015.

Official Website

In the cello number 5 he uses Handel “See the conquering hero comes”. and an aria by Mozart as his Themes. Is there a reason? In most notes about the sonata there is no mention