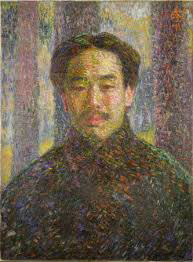

Li Shutong

And at the turn of the 20th century, China was certainly dealing with some serious political adversity. The “Boxer Rebellion” also known as the “Yihequan Movement” violently turned against foreign and Christian influences, and the centralized dynastic power of the Qing fell in the Republican Revolution in 1911. A growing nationalism crystallized as the “May 4th Movement” after the 1919 Versailles Peace settlement, and eventually led to the establishment of the Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party. In a nation struggling to find its way in a new world that held both promise and threat, Beethoven’s personal struggles and his evident genius struck a chord. China, it seemed, fell in love with the “image of Beethoven who went through turmoil, obstacle, and difficulties, but was triumphant in the end.”

And at the turn of the 20th century, China was certainly dealing with some serious political adversity. The “Boxer Rebellion” also known as the “Yihequan Movement” violently turned against foreign and Christian influences, and the centralized dynastic power of the Qing fell in the Republican Revolution in 1911. A growing nationalism crystallized as the “May 4th Movement” after the 1919 Versailles Peace settlement, and eventually led to the establishment of the Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party. In a nation struggling to find its way in a new world that held both promise and threat, Beethoven’s personal struggles and his evident genius struck a chord. China, it seemed, fell in love with the “image of Beethoven who went through turmoil, obstacle, and difficulties, but was triumphant in the end.” Beethoven’s music was first heard in China in a performance by the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra, later to become the Shanghai Symphony on 12 November 1911. Alongside compositions by Weber, Schubert, and Liszt, the program tellingly featured the “Finale” from his Eroica Symphony. That concert, however, was exclusively heard by an expatriate audience, and performed by a foreign-born conductor and orchestral players. The honor of first performing Beethoven with Chinese musicians playing to a Chinese audience fell on the noted Chinese music educator and composer Xiao Youmei. Growing up in Macao, he first studied in Japan and later completed a Ph.D. thesis entitled Historical Research on the Pre-Seventeenth Century Chinese Orchestra at Leipzig University in 1916. Once he returned to China, he served as the review editor for the Republic of China’s Ministry of Education, and in 1919 he was asked to start an orchestra at Beijing University. A follower of Sun Yat-sen, he established the Beijing University Conservatory with about 15 musicians. Nevertheless, they performed the second movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and the first movement of his Sixth Symphony in 1922.

The second movement of Beethoven’s Eroica, performed by organist Allen Artz Wiant, sounded at the funeral of Sun Yat-sen in 1925. With Beethoven becoming ever more popular and political trouble brewing, an extended and heated debate ensued whether the composer could serve capitalist or socialist ideals. Some saw him “as representative of bourgeois decadence, while others saw him as an inspiration for revolution.” In Communist China, music had to meet political as well as aesthetic standards and Beethoven was seen as “the original revolutionary, a man who freed music and could help free the masses as well.” When the People’s Republic of China celebrated its 10th anniversary in 1959, the Central Philharmonic Orchestra performed Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, with Friedrich Schiller’s poem translated into Mandarin. Within a few years, during the darkest days of the Cultural Revolution, however, Beethoven had fallen out of favor and Western classical music was banned. Read more about that in our next episode entitled “Beethoven in China: The Dark Years”

The second movement of Beethoven’s Eroica, performed by organist Allen Artz Wiant, sounded at the funeral of Sun Yat-sen in 1925. With Beethoven becoming ever more popular and political trouble brewing, an extended and heated debate ensued whether the composer could serve capitalist or socialist ideals. Some saw him “as representative of bourgeois decadence, while others saw him as an inspiration for revolution.” In Communist China, music had to meet political as well as aesthetic standards and Beethoven was seen as “the original revolutionary, a man who freed music and could help free the masses as well.” When the People’s Republic of China celebrated its 10th anniversary in 1959, the Central Philharmonic Orchestra performed Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, with Friedrich Schiller’s poem translated into Mandarin. Within a few years, during the darkest days of the Cultural Revolution, however, Beethoven had fallen out of favor and Western classical music was banned. Read more about that in our next episode entitled “Beethoven in China: The Dark Years” Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Central Philharmonic Orchestra/Excerpt)

I published a book on Shanghai in the twenties some years ago (Spoilt Children of Empire) noting among other things that the Shanghai Muncipal Orchestra commemorated Beethoven’s death in 1927 with a performance of the Ninth — all except the last movement (unable to come up with a chorus or soloists, presumably). Mario Paci was the conductor. Somewhat earlier the same orchestra had played Walther’s Preislied from Meistersinger, but it was sung by a mezzo (Mme. L. Spunt). They tried to make the most of what they had, in other words, and that wasn’t much. At the same time I wonder how many of the Shanghai expats in those days knew the difference.