Dorothea Ertmann

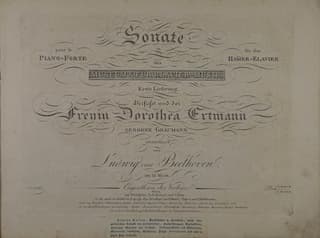

On 16 January 1817 the Wiener Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung announced the forthcoming publication of Beethoven’s A-major sonata op. 101. According to the newspaper, with reference to the title page, the sonata was dedicated to “Freyin Dorothea Ertmann née Graumann.” Beethoven sent Ertmann a copy of the original edition and commented, “You will now receive what was often intended for you, as proof of my attachment to your talents as well as to your person.” Dorothea Ertmann might not be a household name today, but in her time she was universally known as “the greatest performer of Beethoven’s compositions,” and that “she intuitively grasped the most hidden subtleties of Beethoven’s works with as much certainty as if they had been written out before her eyes.” A contemporary critic writes, “without Frau von Ertmann, Beethoven’s piano music would have disappeared from the repertoire even sooner in Vienna.” Beethoven therefore had good reason to venerate her like a priestess of music, and he apparently did call her my “Dorothea-Caecilia,” in reference to the patron saint of music.

Mathilde Marchesi, Dorothea’s niece

Dorothea Ertmann and her family—she had married the Austrian military officer Stephan Leopold Freiherr von Ertmann in 1798—arrived in Vienna in 1802, and by 1803 she had not only made Beethoven’s acquaintance but probably also became his student. A touching anecdote reports that on 19 March 1804, Dorothea lost her three-year-old son Franz Carl. As she subsequently told her niece, the famed singer Mathilde Marchesi, “Beethoven greeted me in silence, he sat down at the piano and fantasized for a long time. Who could describe this music! One thought to hear choirs of angels celebrating the entrance of my poor child into the world of light. Then, when he finished, he squeezed my hand sadly and went silently as he came.” Ertmann frequently performed in the salons of the Viennese nobility and quickly acquired the reputation of being an outstanding Beethoven interpreter. The Beethoven biographer Anton Schindler reports, “this artist in the truest sense of the word excelled particularly in expressing the graceful, delicate and naive, but also in the deep and sentimental… What she achieved here was simply inimitable.” This assessment is echoed by the Beethoven student, Carl Czerny who writes, “Among the women of that time was the Baroness Ertmann the most excellent player of Beethoven’s works. She and her husband were among his most intimate friends, and she played with great physical strength and entirely in the spirit of the works.” Czerny was so mightily impressed that he dedicated his Op. 7 Sonata to Dorothea Ertmann as well.

Carl Czerny: Piano Sonata No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 7 (Anton Kuerti, piano)

Beethoven’s A-major sonata Op. 101

The composer and conductor Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) reported in a letter in 1809, “I had long been told of the wife of Major von Ertmann who is garrisoned near Vienna, is spoken of as a great piano player who performs particularly the greatest Beethovenian things very perfectly. So I was prepared for it, and with great anticipation I went to her sister, the wife of the young banker Franke, who was kind enough to let me know of the arrival of Frau von Ertmann, in order to make her acquaintance. A tall, noble figure and a beautiful, soulful face tensed my expectations even higher at the first sight of the noble woman… I have never seen such power combined with the most intimate tenderness, even with the greatest virtuosos; in each fingertip a singing soul, and in both equally finished, equally secure hands, what power, what power over the whole instrument, everything that art has great and beautiful, singing, speaking and playing must produce! And it was by no means a beautiful instrument such as one so often finds here; the great artist breathed her soulful soul into the instrument and forced services from it that no one else had done before.” And Muzio Clementi, attending a matinee, delightfully uttered several times, “elle joue en grand maître.” We are told that Clementi was a staple of Ertmann’s concert programs.

Muzio Clementi: Keyboard Sonata in C Major, Op. 20 (Pietro Spada, piano)

Beethoven’s greeting card to Dorothea Ertmann, 1803/1804.

Stephan von Ertmann was appointed city commander of Milan in 1824, and the couple lived there until his death. During his trip to Italy in the summer of 1831, the young Felix Mendelssohn introduced himself to Dorothea von Ertmann, and he described his visit in a vivid letter. “She welcomed me very kindly, was also very agreeable, played me the C sharp minor sonata by Beethoven, then the one in D minor… We play music until 1 o’clock in the evenings, yesterday morning they took me for a walk around the area, I had to eat there at noon, there was company in the evening, and they are the most pleasant, educated people you can think of… She plays Beethoven’s things very nicely, although she has not studied for a long time; she often exaggerates a little with the expression and stops too much and then hurries again; but again she plays individual pieces splendidly. I think I learned something from her.” When Stephan Ertmann died in 1835, Dorothea returned to Vienna and played for Ignaz Moscheles, who remarked, “this is an interesting relic of very good piano playing.” Dorothea von Ertmann died in Vienna on 16 March 1849, and she is still remembered as the muse for works by Eberl, Reichardt, and Dessauer. As Beethoven’s high priestess of music, she also performed in the premiere of his third Cello Sonata, Op. 69.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

I would like to know more about your site. What I have read so far has been very enlightening as I consider myself a Beethoven scholar, amateur one at that. music is and always will be my great love. More of the above please.